Ghostly plasma loops linger on the sun after massive solar explosion (photos)

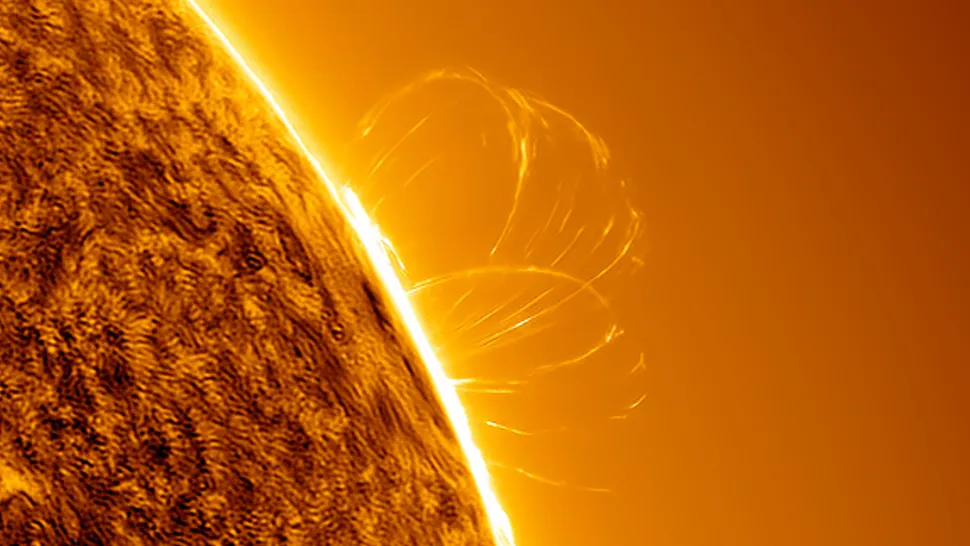

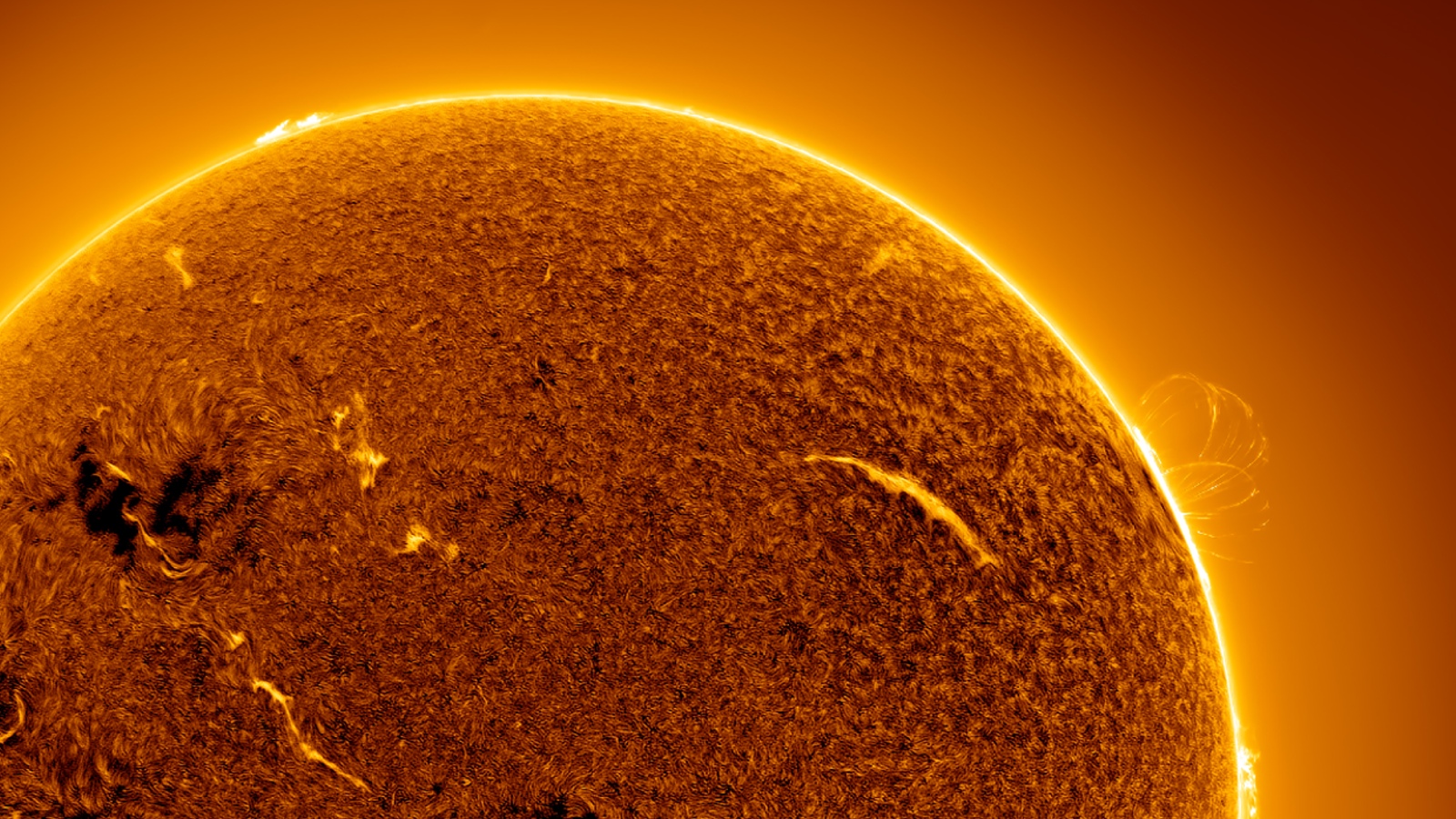

A photographer recently snapped an incredibly detailed photo of gigantic, ghostly plasma loops towering above the sun's fiery surface after a powerful solar flare exploded from the sun.

A series of gigantic yet eerily faint plasma loops temporarily rose above our home star's surface after a powerful solar flare exploded from the sun on Monday, stunning new photos show.

These loops linger like ghostly echoes of the departed solar storm, but scientists still don't know exactly how the ethereal remnants take shape.

On Monday (Jan. 29), a powerful 6.8 magnitude M-class solar flare — the second highest class of solar flares behind X-class flares — erupted from sunspot AR3559 as it began to disappear behind the sun's western limb, according to Spaceweather.com.

Before solar flares explode from the sun, large loops of ionized gas, or plasma, often rise above the sun's surface like giant horseshoes. These plasma loops, or prominences, are held in place by the magnetic field lines of dark-colored sunspots, which eventually snap like an elastic band as solar flares explode, flinging the looped plasma into space as a coronal mass ejection (CME).

The recent stellar explosion launched a CME that was predicted to lightly graze Earth's magnetic field on Feb. 1. But it ended up missing us completely, according to Spaceweather.com.

Related: 15 dazzling images of the sun

However, shortly after Monday's M-class flare, astrophotographer Eduardo Schaberger Poupeau snapped a stunning picture of faint plasma loops towering above the solar surface right where the CME had exploded from. These loops are puzzling, as all the plasma from the area should have theoretically been ejected into space as a CME.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The logic-defying structures are known as post-flare loops (PFLs) and only appear when the sun is viewed with a special filter that enhances red wavelengths of light given off by hydrogen, known as H-alpha, according to NASA.

PFLs are most commonly seen after M-class and X-class flares and often reach heights of around 30,000 miles (50,000 kilometers) above the sun's surface, according to a 2005 study. It is unclear how tall the most recent loops were.

Astronomers have spotted these glowing arches on the sun before and have even seen them in the wake of explosions from nearby stars. The structures are much fainter than the prominences that appear before a solar flare because they contain smaller quantities of plasma that are much cooler and, therefore, give off less light. As a result, few images of PFLs capture the phenomenon in as much detail as Poupeau's new photo.

Related: 10 solar storms that blew us away in 2023

Despite being documented frequently by researchers, there is still some confusion about how PFLs form. Researchers initially believed that the plasma comes from the solar surface and fills in the magnetic field lines after they recover from snapping. However, more recent observations suggest the magnetic loops may actually be pulling back some of the plasma that has been ejected into space by solar flares, according to Spaceweather.com.

The sun is currently nearing the explosive peak in its roughly 11-year solar cycle, known as the solar maximum, which is likely to arrive before the end of the year. As a result, the frequency and power of solar flares is rapidly increasing.

For example, on Dec. 31, 2023, a monstrous X5 solar flare erupted from the sun — the most powerful solar explosion for six years. And on Jan. 22, an extremely rare double solar flare erupted from opposite sides of our home star.

Due to the increasing solar activity, there will be many more PFLs over the coming years, which could shed light on exactly how they form, according to Spaceweather.com.

This story was provided by Space.com's sister site Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Harry is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. He studied Marine Biology at the University of Exeter (Penryn campus) and after graduating started his own blog site "Marine Madness," which he continues to run with other ocean enthusiasts. He is also interested in evolution, climate change, robots, space exploration, environmental conservation and anything that's been fossilized. When not at work he can be found watching sci-fi films, playing old Pokemon games or running (probably slower than he'd like).