The Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) project has started crafting another mirror segment.

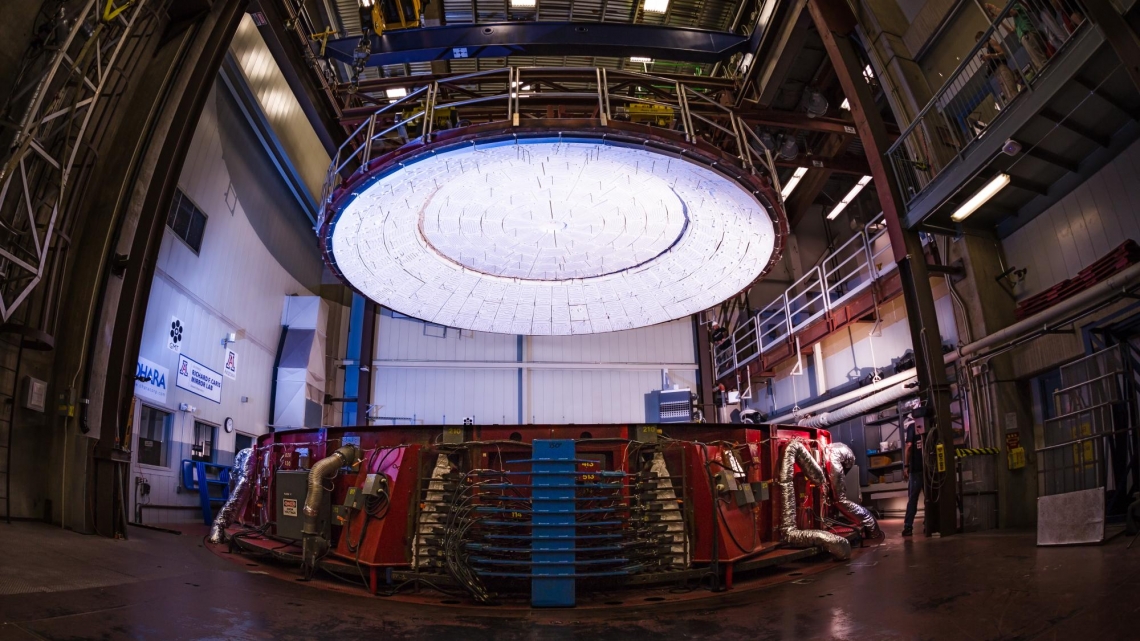

A big furnace containing 20 tons (17.5 metric tons) of pure borosilicate glass began rotating on Friday (March 5) at the University of Arizona's Richard F. Caris Mirror Lab, kicking off the spin-casting process for the sixth of seven elements that will make up the GMT's 82-foot-wide (25 meters) primary mirror.

"The spin-casting is undeniably the most spectacular part of the manufacturing process," Buddy Martin, polishing scientist at the mirror lab, said in a statement.

Related: The Giant Magellan Telescope envisioned in Chile (images)

The furnace began heating the glass on Monday (March 1) and reached a peak temperature of 2,129 degrees Fahrenheit (1,165 degrees Celsius) on Saturday afternoon (March 6). At such high temperatures, the melted glass flows like honey, pushed outward by centrifugal force to create a curved shape that would take months to achieve by grinding, Martin explained during a call with reporters on Friday.

Up next is a lengthy "annealing" process, which will cool the glass in stages over the next few months. Around June 1, the team will take apart the furnace "and finally get a look at this mirror," Martin said in Friday's call.

But the 27.6-foot-wide (8.4 m) mirror won't be done at that point. Far from it; technicians will still need to grind and polish it with mind-boggling precision, ensuring that its surface is perfect to within one millionth of an inch.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If the mirror were expanded to the size of North America, 3,500 miles [5,630 kilometers] in diameter, then the average hill would be two-thirds of an inch [1.7 centimeters] tall and the average valley two-thirds of an inch deep," Martin said. "That's how smooth this mirror has to be for it to make the sharpest images that nature will allow."

As you can imagine, shaping the mirror so skillfully is a time-consuming process: It currently takes the Richard F. Caris Mirror Lab about four years to finish each GMT segment. The first two mirrors are done and have been placed in storage in Tucson, and the third is less than a year from completion, project team members said.

Segments four and five were cast in September 2015 and November 2017, respectively, and number seven is expected to be cast in 2023. An eighth element will also be cast, for use as a replacement when maintenance work is performed on one of the seven originals.

All of this equipment and more will eventually head to the Chilean Andes, where construction of GMT infrastructure is well underway. If all goes according to plan, the big telescope will start studying the heavens in the late 2020s, team members said.

These "first light" observations will likely be made with just four of the seven segments installed. That bare-bones GMT will be bigger than any telescope operating today, Giant Magellan Telescope Organization (GMTO) project manager James Fanson said during Friday's call.

The final telescope will be even more powerful, of course, and not just because of its raw light-collecting area. The seven primary mirrors will be complemented by seven smaller "adaptive secondary mirrors," each of which will bend about 1,000 times every second to counteract the blurring effect of Earth's atmosphere. In the end, the GMT's vision will be about 10 times sharper than that of the famous Hubble Space Telescope, project team members said.

"The leap in sensitivity and resolution that we're going to make with GMT will revolutionize our understanding of all areas of astronomy, from the formation and evolution of objects we can see, like planets, stars, black holes and galaxies, to cosmology and the things we can't directly see, like the nature of dark matter and dark energy," GMTO chief scientist Rebecca Bernstein said during the call.

For example, GMT will be able to directly image a number of nearby exoplanets and also analyze the composition of their atmospheres, Bernstein said.

"GMT is the latest in a long quest of humanity to understand our place in the universe — where we come from, what our cosmic destiny is and whether we are alone or not in the universe," Fanson told Space.com. "It strikes very profoundly at who we are as human beings."

Two other ground-based megascopes could join that quest relatively soon as well. The Extremely Large Telescope and the Thirty Meter Telescope will get up and running later this decade in Chile and Hawaii, respectively, if all goes according to plan.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.