What are gluons?

These force-carrying particles are the glue that binds baryonic matter together.

Gluons are suitably named because they are the 'glue' that binds quarks together to form the likes of protons and neutrons.

They are the carriers of the strong force, one of the four fundamental forces. Force-carrying particles such as the gluon, as well as the photon for the electromagnetic force, and the W and Z bosons for the weak force, are all massless particles with a quantum spin of 1 and are referred to collectively as 'gauge bosons'.

Gluons and quarks are inextricably linked. Quarks are the elementary particles that form hadrons, which are particles made of two or three quarks. For example, protons and neutrons, which form atomic nuclei, are hadrons, and therefore exist because of quarks and gluons. Although they are connected with gluons, quarks differ in that their quantum spin is 1/2, and they have a mass, albeit a tiny one (for example, an 'up' quark has a mass of 2.01 MeV, and a 'down' quark is slightly heavier with a mass of 4.79 MeV, which are a fifth and half the mass of a proton respectively; in terms of kilograms they are about 3.56 x 10–30kg). What quarks and gluons have in common is that neither can exist as free particles, and neither can exist without the other.

Related: 10 mind-boggling things you should know about quantum physics

Evidence for gluons

Although physicists can't see individual gluons, we know they exist because of indirect evidence that can only be explained by the presence of gluons.

Gluons were first detected in 1979, in an experiment at the Positron Electron Tandem Ring Accelerator (PETRA) at the Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY) Laboratory in Germany. PETRA is a 1.4-mile (2.3-km) long ring, a bit like a miniature version of the Large Hadron Collider except that PETRA accelerates leptons, specifically electrons and their antimatter equivalents positrons, rather than protons and atomic nuclei.

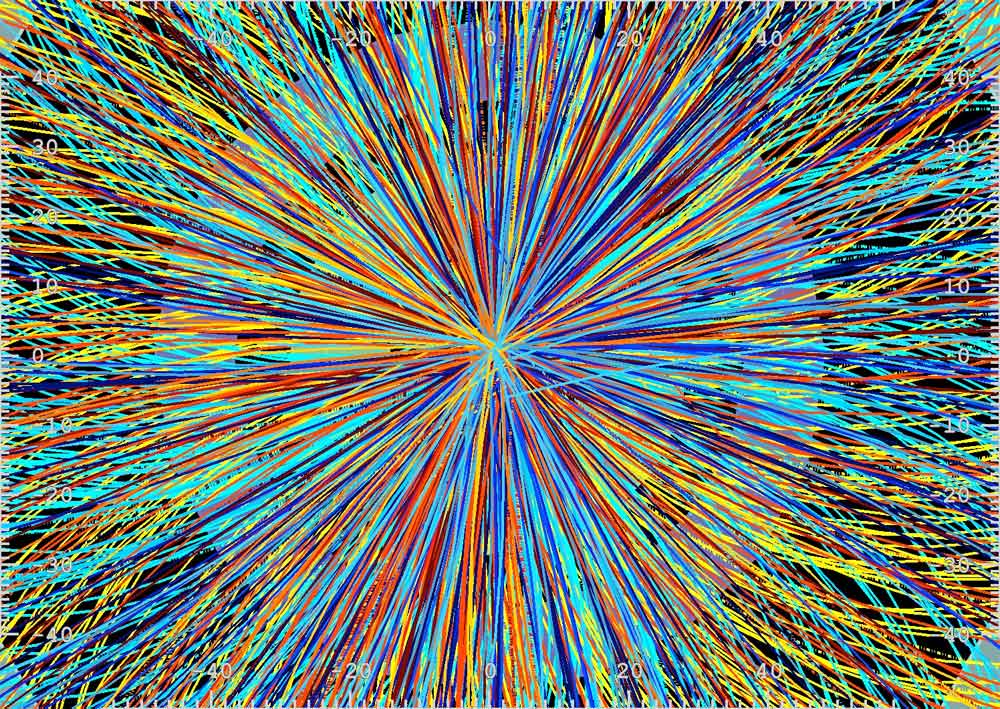

When matter and antimatter come together it annihilates. In the case of smashing electrons into positrons, the pair annihilate and release a quark and an antiquark. The two quarks are unable to escape each other — the farther they try to move apart, the stronger the strong force between them becomes (at least up to a point, about 10^–15 m, or a femtometer), the excess stored energy allowing the quark and antiquark pair to decay, or 'hadronize', into hadron particles that form in a conic region along the directions of travel of the original quark and antiquark. This conic region of hadron particles is called a jet, and a simple electron-positron annihilation would produce two opposite jets corresponding to the quark and antiquark.

However, if gluons are real, then the electron-positron annihilation should also produce a gluon alongside the quark-antiquark pair, and this gluon should also hadronize into a third jet. To conserve momentum, the gluon would carry away some of the momentum from one of the quarks, changing the direction of its jet so that the hadronized jets from the quarks would no longer be directly opposite one another, while the gluon-derived jet would be off to one side. This is indeed what was seen in the PETRA experiment, and in subsequent experiments too, confirming the existence of the gluon.

Gluon FAQ's answered by an expert

We asked Markus Diehl, an expert in quantum chromodynamics at the DESY Theory Group a few frequently asked questions about gluons.

Markus Diehl is an expert in quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory that covers the interactions of quarks and gluons (the strong force).

How do we know gluons exist?

A wealth of very precise measurements is correctly explained by our theory of quarks and gluons. A rather direct — and historically the first — manifestation of gluons is the production of three distinct sprays of particles in electron-positron collisions. These events with three hadronic jets, as we call them, were first observed at DESY’s PETRA collider in 1979.

Why are gluons important?

Gluons are responsible for binding quarks together and thus for the formation — and many properties — of protons and neutrons, the building blocks of atomic nuclei.

Can gluons and quarks ever be separated?

For all we know, quarks and gluons cannot be observed as free particles, but they give rise to hadronic jets. Looking closely at the distributions of the particles in a jet, one can actually determine whether it originated most likely from a gluon or from a quark.

Color charge and quantum chromodynamics

The quantum theory that governs the physics of the strong force that is carried by gluons to bind quarks together is called quantum chromodynamics, or QCD. Named by the famous Nobel-prize-winning particle physicist Murray Gell-Mann, QCD revolves around the existence of a property of quarks and gluons called 'color charge', as described by physicists at Georgia State University. This is neither a real color nor a real electric charge (gluons are electrically neutral) — it is so-named because it is analogous to electric charge in the sense that it is the source of the strong force's interactions between quarks and gluons, just as the charge is the source of the interaction in the electromagnetic force, while the colors are just an arbitrary, albeit quirky, way to distinguish between different quarks and the interactions they have with the strong force via gluons.

Quarks can have a color charge referred to as either red, green or blue, and there are positive and negative (anti) versions of each. The quarks are able to change color in their interactions, and the gluons conserve the color charge. For example, if a green quark changes to a blue quark, the gluon must be able to carry a color charge of green-blue. Accounting for all the different color and anti-color combinations means that there must be 8 different gluons in total, as described by John Baez. Compare this to the electromagnetic force, which operates under the theory of quantum electrodynamics (QED) in which there are only two possible charges, positive or negative. QCD is far more complex than QED!

The quark-gluon plasma

It's not strictly true that gluons and quarks cannot be separated, but it requires very extreme conditions that have not existed in nature since the first tiny fractions of a second after the Big Bang.

A few trillionths of a second after the Big Bang, the temperature of the tiny universe was still immense at a thousand trillion degrees. During that time, before any hadrons had even formed, the infant universe was filled with a soup of free quarks and gluons known as the quark-gluon plasma (plus leptons such as neutrinos and electrons). Because the universe was so hot, the quarks and gluons were whizzing around unbound at light speed, bouncing off each other with too much energy even for the strong force to bind them.

The universe very quickly cooled as it expanded, and by the first millionth of a second, the temperature had dropped sufficiently, to 2 trillion degrees, to allow the strong force to bind quarks and gluons together to form the first hadrons.

It is possible to replicate the primordial quark-gluon plasma in particle accelerator experiments, such as those at CERN or at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider at Brookhaven National Laboratory.

The atomic nuclei of heavy elements such as gold or lead are smashed together at almost the speed of light, resulting in a miniature fireball that for a brief moment is hot enough to dissolve hadrons into a quark-gluon plasma.

Almost instantaneously the fireball cools and the quarks and gluons recombine to form jets of hadrons, including mesons that consist of two quarks, and baryons that are made of three quarks. The quark-gluon plasma is extremely dense, and often the hadron jets struggle to get through and lose energy. Physicists call this 'quenching', as described by physicists at CERN, and the amount of quenching, as well as the overall distribution and energy of the jets, can provide great insights into the properties of the quark-gluon plasma. For example, physicists have learned that it behaves more like a perfect fluid that flows with zero viscosity, than a gas. By learning about properties such as these, recreating the quark-gluon plasma in particle accelerators can give scientists a window back in time to the very birth of the universe and the immediate aftermath of the Big Bang when matter first came into being.

Additional resources

Read the story of the discovery of gluons in 1979, as told by DESY physicists Ilka Flegel and Paul Söding in the CERN Courier. Discover the history of QCD, as told by one of its pioneers, Harald Fritzsch. Explore quarks and gluons in more detail with these resources from The Department of Energy. Explore the discovery of the gluon and journey back in time to the 70s with this article from DESY.

Follow Keith Cooper on Twitter @21stCenturySETI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Bibliography

Particle Physics, by Brian R. Martin (2011, One-World Publications)

Origins of the Universe: The Cosmic Microwave Background and the Search for Quantum Gravity, by Keith Cooper (2020, Icon Books)

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

-

rod https://forums.space.com/threads/quarks-what-are-they.58460/Reply

Som recent discussion on quarks and gluons, relative to how the BB cosmology created this interesting stuff in nature :) -

Sean Autrey Reply

But would gluons be the "line" and not the inductant spheres in this model correct. Or is it defines as an elementary particle that's resonances equal it's mass. By the spaces between the objects? Isn't it the same as gravity... And a chip off a larger piece of metal?... It behaves differently because of it's scale? Volume wise pressure over induction would be faster I guess... So it's hard to say whether soft or hard came first... Maybe it's just this rotational energy...and nothing else .. but it behaves differently based on the shape right...Admin said:Discover how gluons bind quarks together to form protons and neutrons and explore the form weird form of matter in which they existed just after the Big Bang.

What are gluons? : Read more -

Sean Autrey Reply

supposedly it began with fractaling of triangular shapes...like mirroring. Transparent.. and this happened fast.. do you say this gluon is matter... Or a wave.Sean Autrey said:But would gluons be the "line" and not the inductant spheres in this model correct. Or is it defines as an elementary particle that's resonances equal it's mass. By the spaces between the objects? Isn't it the same as gravity... And a chip off a larger piece of metal?... It behaves differently because of it's scale? Volume wise pressure over induction would be faster I guess... So it's hard to say whether soft or hard came first... Maybe it's just this rotational energy...and nothing else .. but it behaves differently based on the shape right...