Greenhouse gas monitoring from space to get a boost with SpaceX launch

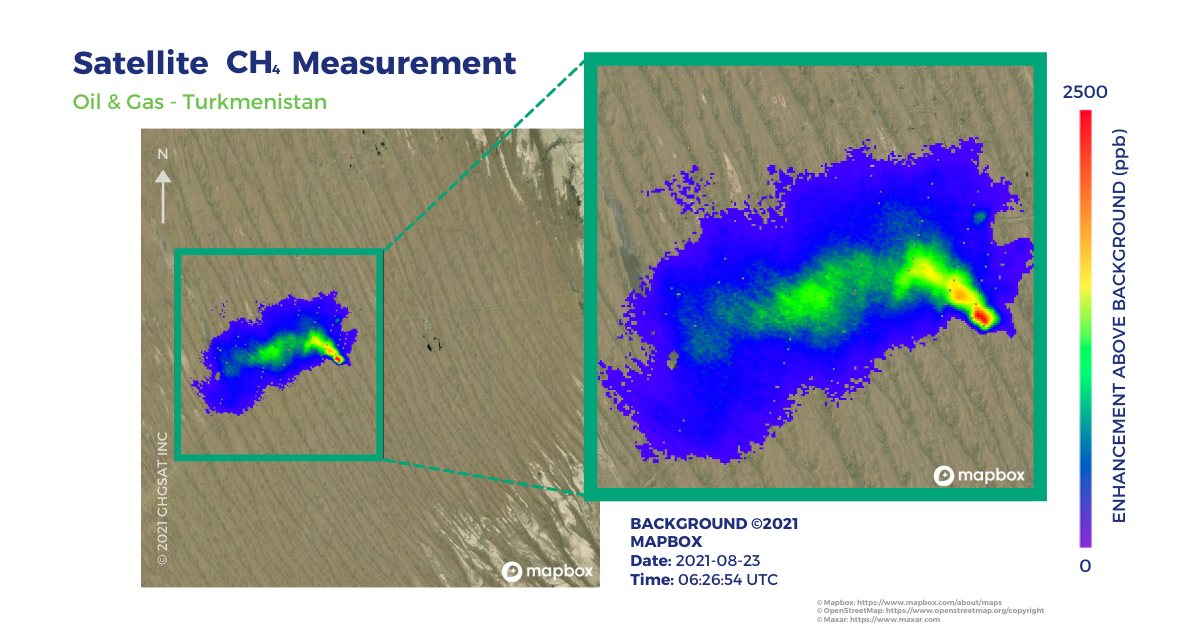

GHGSat detects methane, a greenhouse gas that is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Three greenhouse gas-detecting satellites will travel to space on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket Wednesday (May 25) to improve emissions monitoring from space.

The satellites belong to Canada-based GHGSat, which currently runs the world's largest greenhouse gas-monitoring satellite constellations. The new additions will double the company's fleet, enabling it to spot polluters more quickly and accurately. GHGSat detects methane, a greenhouse gas that is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide.

Studies using GHGSat data, as well as those captured by Europe's Sentinel satellites, previously revealed large amounts of preventable methane emissions leaking from oil and gas processing facilities all over the world due to negligence and faulty technology.

Related: Satellites reveal record-high methane concentrations despite reduction pledges

GHGSat can track those emissions down to individual plants, refineries and pipelines, providing authorities with a tool to hold those climate offenders accountable.

"In 2021, with three satellites in orbit, GHGSat measured over 143 million tons of carbon dioxide equivalent in methane emissions around the world," GHGSat representatives said in an emailed statement. "The company's data is routinely used by oil and gas, landfill, and coal mine operators to understand and reduce their emissions. It is also being utilized by the United Nations Environment Program's International Methane Emissions Observatory (IMEO) to help countries meet their commitments."

At the COP26 United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow, Scotland, in November 2021, world leaders pledged to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030 — a goal described by many scientists as easily achievable given that a large proportion of these emissions is preventable.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Currently, countries report their emissions based on the activity of the various industries and the amount of fossil fuels they use. However, this method results in delays and is unreliable as it doesn't account for any leaks and relies on self-reporting. Satellites, therefore, are expected to provide more precise data and in real time.

According to the European Commission, methane is responsible for at least a quarter of the current global warming. Eliminating unwanted methane emissions could reduce the projected atmospheric warming by 0.5 degrees Fahrenheit (0.28 degrees Celsius) by 2050.

GHGSat made headlines earlier this year by achieving a first: measuring the amount of methane released by burping cows.

The company plans to further expand its constellation with four more satellites, which are expected to launch in 2023.

Other players are developing greenhouse gas-detecting satellites as well. The European Space Agency and the European Union's Copernicus environment monitoring program are working on a mission called CO2M, which will be the first to directly monitor carbon dioxide emissions at the level of individual emitters. Monitoring carbon dioxide emissions from space is much more challenging than detecting methane, because of the much higher background concentrations of this gas in Earth's atmosphere.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.