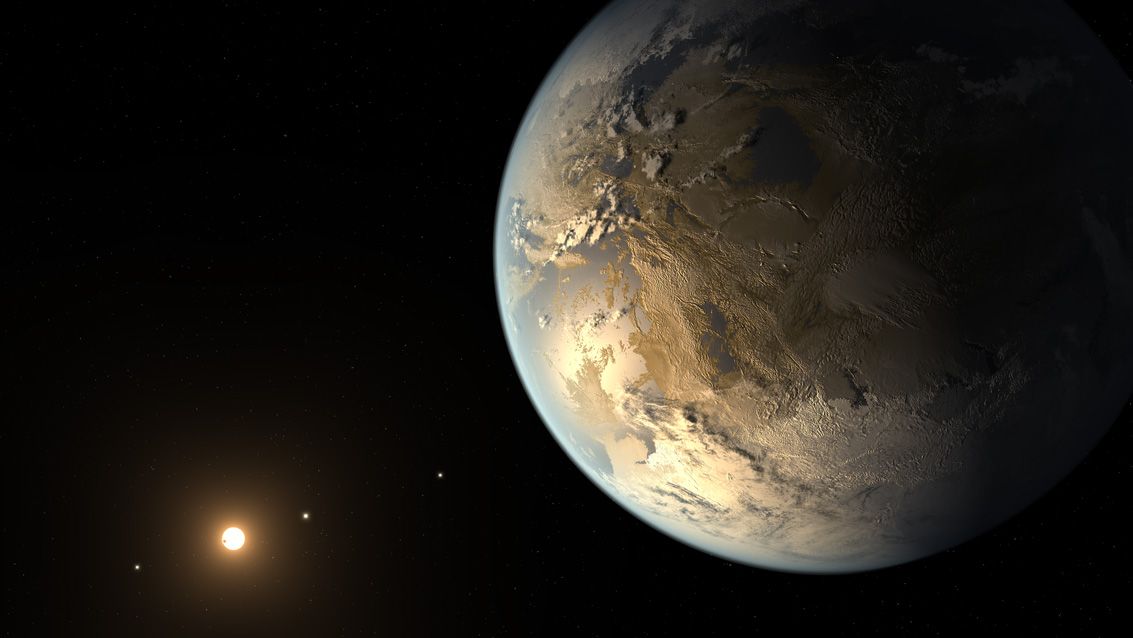

Our Milky Way galaxy abounds with potentially Earth-like planets, a new study suggests.

On average, each sunlike star in the Milky Way likely harbors between 0.4 and 0.9 rocky planets in its "habitable zone," the just-right range of orbital distances where liquid water could be stable on a world's surface, researchers have found.

About 7% of the Milky Way's 200 billion or so stars are "G dwarfs" like the sun, so that's a lot of possibly Earth-like real estate.

Related: 10 exoplanets that could host alien life

"This is the first time that all of the pieces have been put together to provide a reliable measurement of the number of potentially habitable planets in the galaxy,” study co-author Jeff Coughlin, an exoplanet researcher at the SETI (Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence) Institute in Mountain View, California, said in a statement.

"This is a key term of the Drake Equation, used to estimate the number of communicable civilizations," said Coughlin, who also directs the Kepler Science Office, which is dedicated to analyzing data gathered by NASA's planet-hunting Kepler space telescope. "We're one step closer on the long road to finding out if we’re alone in the cosmos."

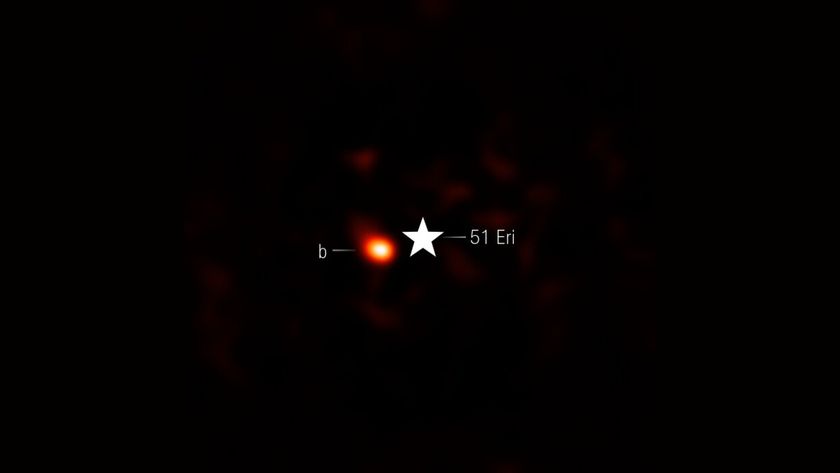

In the new study, a large team led by Steve Bryson of NASA's Ames Research Center in California pored over observations by Kepler, which operated from 2009 through 2018. The spacecraft was incredibly prolific, discovering more than 2,800 exoplanets to date — nearly two-thirds of all known alien worlds. And Kepler's tally continues to grow as researchers keep sifting through its huge dataset; thousands of Kepler "candidates" await vetting by further analyses and observations.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Bryson and his colleagues also examined data on stellar properties from the European Space Agency's Gaia spacecraft, which is precisely mapping a billion Milky Way stars.

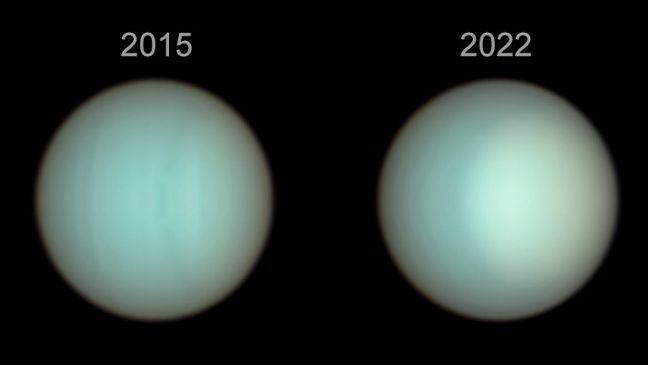

The team used this information to estimate occurrence rates for rocky planets in the habitable zones of sunlike stars. The scientists defined "rocky planets" as worlds with diameters 0.5 to 1.5 times that of Earth, and sunlike stars as those with surface temperatures between 8,180 and 10,880 degrees Fahrenheit (4,527 to 6,027 degrees Celsius). Most of the stars that meet that criterion are G dwarfs and "K dwarfs," which are slightly smaller than G dwarfs and about twice as numerous.

The habitable zone (HZ) is a decidedly squishy concept; whether a planet resides in it depends on the thickness and composition of its atmosphere and the activity level of its host star, among other factors. (Other caveats deserve mention as well: The habitable zone is tailored to water-dependent Earth-like life, and it doesn't consider subsurface liquid water, which can exist on very cold, airless worlds, as some of the moons of Jupiter and Saturn show.)

Related: How habitable zones for alien planets and stars work (infographic)

So Bryson and his team calculated occurrence rates for both a "conservative" and an "optimistic" habitable zone — 0.37 to 0.60 planets per star for the former and 0.58 to 0.88 planets per star for the latter.

Both of those ranges have large uncertainties. But the abundances nevertheless imply that potentially Earth-like worlds are all around us — including in our own solar system's backyard.

"We estimate with 95% confidence that, on average, the nearest HZ planet around G and K dwarfs is ∼6 pc [parsecs] away, and there are ∼ 4 HZ rocky planets around G and K dwarfs within 10 pc of the sun," the researchers wrote in the new study, which has been accepted for publication in The Astronomical Journal. You can read a preprint of it for free at arXiv.org. (One parsec is about 3.26 light-years.)

The new research did not consider red dwarfs, also known as M dwarfs, which make up about three-quarters of the Milky Way's stellar population. A 2013 study based on Kepler data estimated that about 6% of red-dwarf systems boast a roughly Earth-like planet in the habitable zone, and one such world is the closest alien world to our solar system, at a distance of merely 4.2 light-years — Proxima b, which orbits the red dwarf Proxima Centauri.

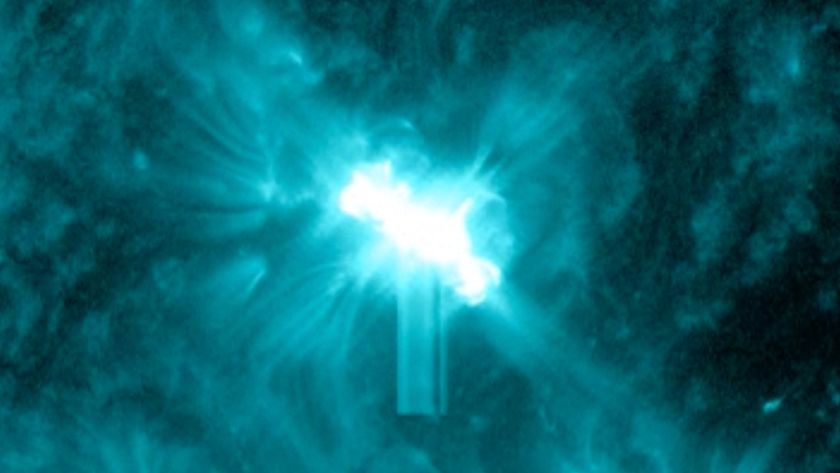

But the true habitability of planets in red-dwarf systems is a matter of debate. Because these stars are so dim, their habitable zones lie very close-in, meaning that planets in this region are likely tidally locked, always showing the same face to their host star, just as the moon does to Earth. Red dwarfs are also much more active than sunlike stars, especially in their youth. So, intense flaring may quickly strip away the atmospheres of worlds that circle in a red dwarf's habitable zone, scientists say.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.