Hackers could shut down satellites — or turn them into weapons

Last month, SpaceX became the operator of the world's largest active satellite constellation. As of the end of January, the company had 242 satellites orbiting the planet with plans to launch 42,000 over the next decade. This is part of its ambitious project to provide internet access across the globe. The race to put satellites in space is on, with Amazon, U.K.-based OneWeb and other companies chomping at the bit to place thousands of satellites in orbit in the coming months.

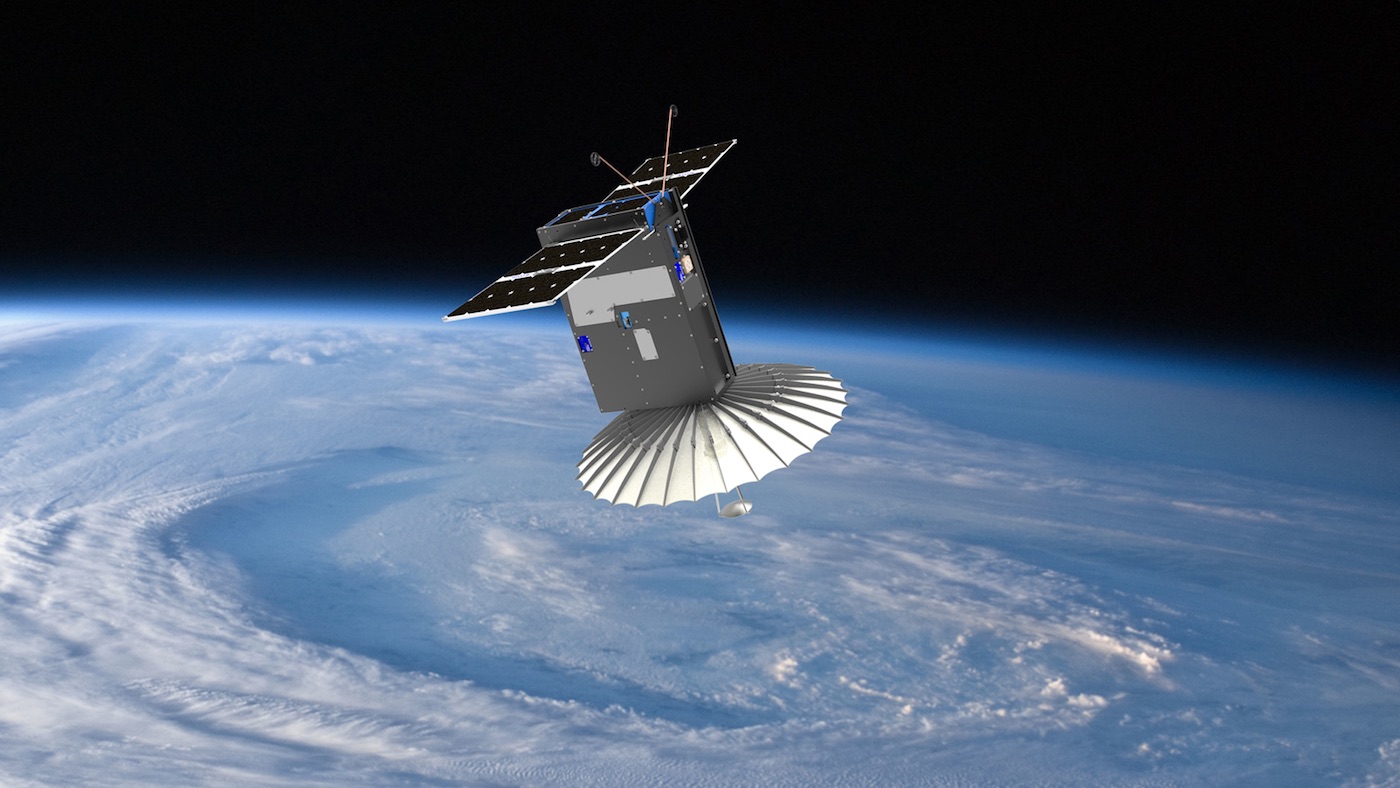

These new satellites have the potential to revolutionize many aspects of everyday life — from bringing internet access to remote corners of the globe to monitoring the environment and improving global navigation systems. Amid all the fanfare, a critical danger has flown under the radar: the lack of cybersecurity standards and regulations for commercial satellites, in the U.S. and internationally. As a scholar who studies cyber conflict, I'm keenly aware that this, coupled with satellites' complex supply chains and layers of stakeholders, leaves them highly vulnerable to cyberattacks.

If hackers were to take control of these satellites, the consequences could be dire. On the mundane end of scale, hackers could simply shut satellites down, denying access to their services. Hackers could also jam or spoof the signals from satellites, creating havoc for critical infrastructure. This includes electric grids, water networks and transportation systems.

Related: Why SpaceX's Starlink satellites caught astronomers off guard

Some of these new satellites have thrusters that allow them to speed up, slow down and change direction in space. If hackers took control of these steerable satellites, the consequences could be catastrophic. Hackers could alter the satellites' orbits and crash them into other satellites or even the International Space Station.

Makers of these satellites, particularly small CubeSats, use off-the-shelf technology to keep costs low. The wide availability of these components means hackers can analyze them for vulnerabilities. In addition, many of the components draw on open-source technology. The danger here is that hackers could insert back doors and other vulnerabilities into satellites' software.

The highly technical nature of these satellites also means multiple manufacturers are involved in building the various components. The process of getting these satellites into space is also complicated, involving multiple companies. Even once they are in space, the organizations that own the satellites often outsource their day-to-day management to other companies. With each additional vendor, the vulnerabilities increase as hackers have multiple opportunities to infiltrate the system.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Hacking some of these CubeSats may be as simple as waiting for one of them to pass overhead and then sending malicious commands using specialized ground antennas. Hacking more sophisticated satellites might not be that hard either.

Satellites are typically controlled from ground stations. These stations run computers with software vulnerabilities that can be exploited by hackers. If hackers were to infiltrate these computers, they could send malicious commands to the satellites.

A history of hacks

This scenario played out in 1998 when hackers took control of the U.S.-German ROSAT X-Ray satellite. They did it by hacking into computers at the Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland. The hackers then instructed the satellite to aim its solar panels directly at the sun. This effectively fried its batteries and rendered the satellite useless. The defunct satellite eventually crashed back to Earth in 2011. Hackers could also hold satellites for ransom, as happened in 1999 when hackers took control of the U.K.'s SkyNet satellites.

Over the years, the threat of cyberattacks on satellites has gotten more dire. In 2008, hackers, possibly from China, reportedly took full control of two NASA satellites, one for about two minutes and the other for about nine minutes. In 2018, another group of Chinese state-backed hackers reportedly launched a sophisticated hacking campaign aimed at satellite operators and defense contractors. Iranian hacking groups have also attempted similar attacks.

Although the U.S. Department of Defense and National Security Agency have made some efforts to address space cybersecurity, the pace has been slow. There are currently no cybersecurity standards for satellites and no governing body to regulate and ensure their cybersecurity. Even if common standards could be developed, there are no mechanisms in place to enforce them. This means responsibility for satellite cybersecurity falls to the individual companies that build and operate them.

Market forces work against space cybersecurity

As they compete to be the dominant satellite operator, SpaceX and rival companies are under increasing pressure to cut costs. There is also pressure to speed up development and production. This makes it tempting for the companies to cut corners in areas like cybersecurity that are secondary to actually getting these satellites in space.

Even for companies that make a high priority of cybersecurity, the costs associated with guaranteeing the security of each component could be prohibitive. This problem is even more acute for low-cost space missions, where the cost of ensuring cybersecurity could exceed the cost of the satellite itself.

To compound matters, the complex supply chain of these satellites and the multiple parties involved in their management means it's often not clear who bears responsibility and liability for cyber breaches. This lack of clarity has bred complacency and hindered efforts to secure these important systems.

Regulation is required

Some analysts have begun to advocate for strong government involvement in the development and regulation of cybersecurity standards for satellites and other space assets. Congress could work to adopt a comprehensive regulatory framework for the commercial space sector. For instance, they could pass legislation that requires satellites manufacturers to develop a common cybersecurity architecture.

They could also mandate the reporting of all cyber breaches involving satellites. There also needs to be clarity on which space-based assets are deemed critical in order to prioritize cybersecurity efforts. Clear legal guidance on who bears responsibility for cyberattacks on satellites will also go a long way to ensuring that the responsible parties take the necessary measures to secure these systems.

Given the traditionally slow pace of congressional action, a multi-stakeholder approach involving public-private cooperation may be warranted to ensure cybersecurity standards. Whatever steps government and industry take, it is imperative to act now. It would be a profound mistake to wait for hackers to gain control of a commercial satellite and use it to threaten life, limb and property — here on Earth or in space — before addressing this issue.

[You're smart and curious about the world. So are The Conversation's authors and editors. You can get our highlights each weekend.]

- How much space junk hits Earth?

- In Photos: A Look at China's Space Station That's Crashing to Earth

- Earth from Above: 101 Stunning Images from Orbit

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

William Akoto is an Assistant Professor of International Politics at Fordham University. His research examines the political economy dynamics of international trade, coup d’états and cyber conflict. His work has appeared in various leading journals and edited volumes. Prior to joining Fordham, he served as a postdoctoral research fellow at the One Earth Future Foundation and the Josef Korbel School of International Studies at the University of Denver. He earned his PhD in Political Science from the University of South Carolina in 2019. Details of his forthcoming papers and current projects are available on his website.