Japan's asteroid samples faced surprise challenges on Earth: A pandemic, traffic jams and airport security

Please do not put your asteroid samples in an airplane's overhead bins.

Collecting rocks from an asteroid is rocket science; getting them to the lab is another story.

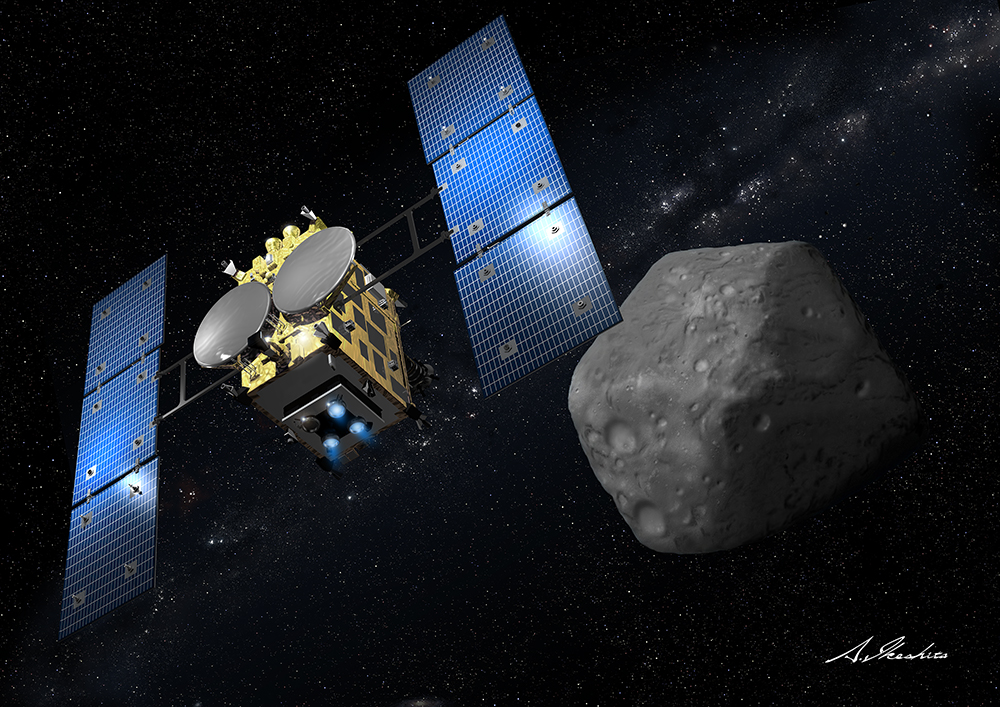

Take Japan's Hayabusa2 mission, which launched in 2014 to grab pieces of a near-Earth asteroid called Ryugu and delivered those samples to Earth in December 2020. Even when the space rocks reached Japan, the traveling wasn't quite over. That's because some of the asteroid material had another flight to catch in order to reach NASA's Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science (ARES) center at Johnson Space Center (JSC) in Texas.

This trip didn't need any rocket fuel, but that doesn't mean it was easy. "This one is, I would say, a really big deal," Keiko Nakamura-Messenger, who until last month was a cosmochemist at JSC, told Space.com. "This is the first time that we did international samples like this."

Related: Japanese scientists 1st peek inside Hayabusa2 asteroid sample capsule

Ryugu rocks from space

NASA received a few grains of asteroid dust from Japan's predecessor mission, Hayabusa, which delivered samples from an asteroid called Itokawa in 2010. However, that spacecraft faced serious challenges during the actual mission and ended up bringing very little material back to Earth.

Hayabusa2 was more successful, bringing 0.2 ounces (5.4 grams) — 50 times the target amount — of precious asteroid cargo to Earth in a capsule that landed in the Australian desert in December 2020. As a partner on the mission, NASA was to receive 10% of that to add to its collection of moon rocks, meteorites and other celestial material held at JSC.

Nakamura-Messenger had planned to fly first to Australia to greet the sample with mission personnel, but stayed home due to the COVID-19 peak occurring at the time. Then, she was meant to visit Japan this year to select NASA's samples and bring them back across the ocean. "I was supposed to go to pick up the sample — that's the polite way, because it's a sort of gift from them to us," she said. But that plan, too, fell afoul of the ongoing coronavirus pandemic; Japan had restrictions in place that banned non-citizens from entering the country.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The biggest hiccup was this pandemic," Nakamura-Messenger said of the sample transfer process. "Everything just kind of went against our wish."

So, as with so many other big moments last year, sample selection went digital. Nakamura-Messenger pored through a JAXA database cataloging each sample of asteroid rock from Ryugu, looking for a variety of sizes, colors and textures among the material. "We want to keep [the samples] as mysterious as possible, as unprocessed as possible," she said.

Then two JAXA personnel flew the precious cargo to Texas.

An asteroid carry-on

The logistics were astronomical, so to speak. After withstanding the cold vacuum of space and the blaze of plunging through Earth's atmosphere, now the priceless asteroid samples faced the drab routine of modern commercial air travel.

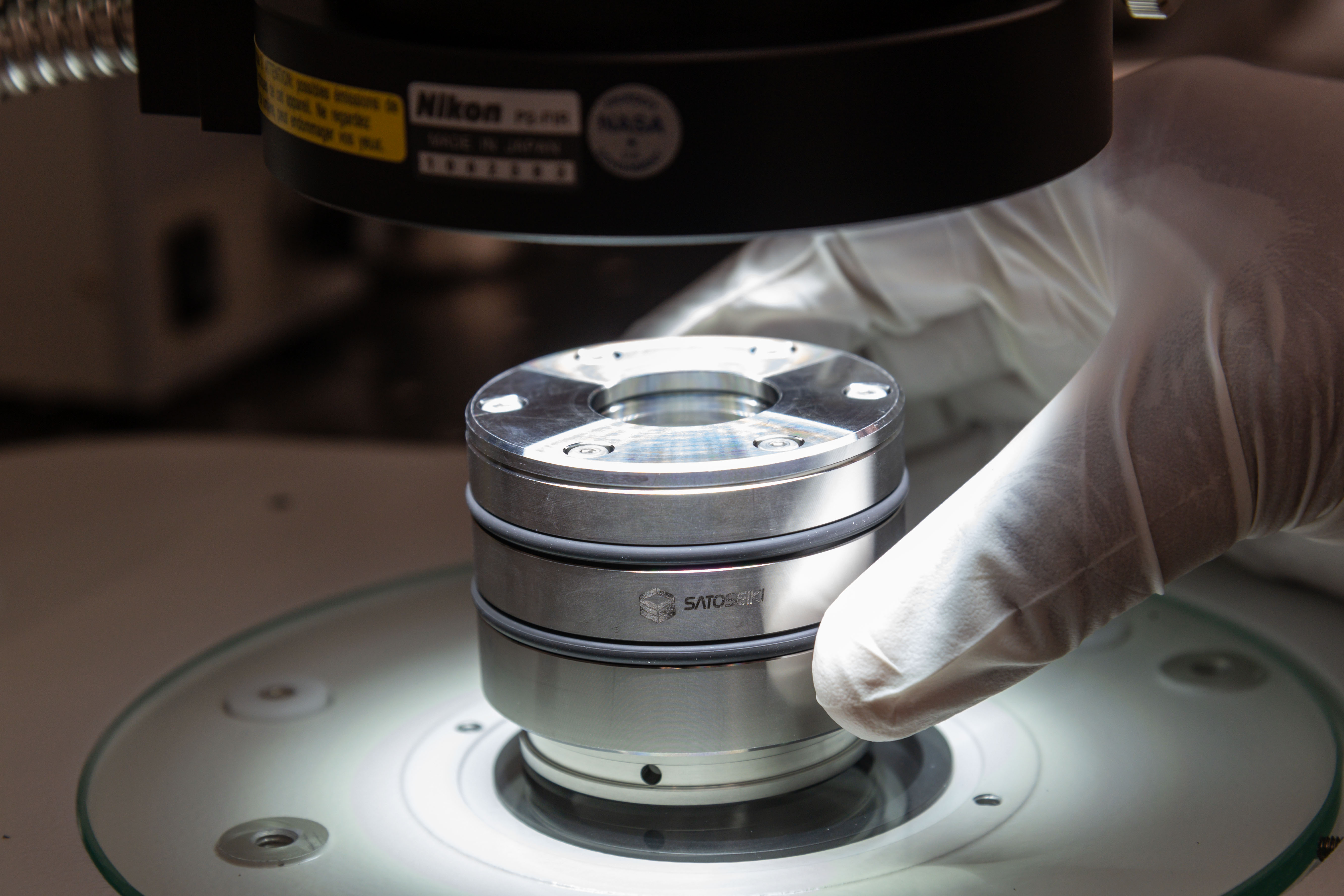

"Of course, we don't want to check them, we had to hand-carry all the way," Nakamura-Messenger said. JAXA brought NASA the samples packed into 29 squat, super-sophisticated cylinders; these were packed into four military-grade suitcases that had to remain upright throughout the journey, she noted.

The first challenge was getting the unusual cases safely past the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). "We had to coordinate with TSA to not disturb the sample," Nakamura-Messenger said. "We certainly didn't want samples to go through the X-ray."

Then to board the plane: At 22 pounds (10 kilograms) each and two per JAXA staffer, the cases put each passenger well over the airline's typical weight limit for carry-on baggage. And no, asteroid samples are not the sort of thing one stashes in the overhead bins. The airline offered the cases two seats of their own and helped the JAXA representatives watch over them.

After a safe flight, the Ryugu samples and their chaperones touched down in Houston.

It was a stressful journey even for those who didn't travel, since concern about the omicron variant of COVID-19 was just beginning to spike. "We couldn't sleep much that several days," Nakamura-Messenger said. "We didn't know what Japan's government was going to announce next." And to top it off, of course, the JAXA employees arrived just after Thanksgiving, the busiest time for air travel in the U.S.

Lest the space rock meet that most terrestrial of travel hassles — traffic — NASA personnel worked with airport security for access and held rehearsals to compare different routes from the airport to JSC, Nakamura-Messenger said. "It was right after Thanksgiving so the airport was quite busy," she said.

But everything went smoothly, with the samples arriving at JSC on Nov. 30, 2021; the JAXA delegation returned to Japan just two days before the government instituted stricter travel regulations in response to the omicron variant of COVID-19, Nakamura-Messenger said. "They barely made it."

Another round next year

Hayabusa2 wasn't the only asteroid-sampling mission of recent years; NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft grabbed rocks from another near-Earth asteroid, called Bennu, in October 2020. That mission is now on its way home to deliver the samples in September 2023. That delivery will land in the Utah Test and Training Range (UTTR), as previous NASA missions have in the past — most recently, the 2006 return of the Stardust comet-sampling mission.

The explosive-studded range is the first stop for fresh celestial materials on Earth despite its hazards because it is the largest secure area in the central United States. "There are areas that we cannot step in because it's too dangerous," Nakamura-Messenger said. The OSIRIS-REx sample-return capsule, however, is equipped with technology to ensure it touches down in a safe spot.

From there, the space rocks will board a NASA plane to Ellington Field, northwest of JSC, where a ground convoy like the one that shepherded the Ryugu samples from the airport will see the rocks along the last leg of the journey.

But some of that rock will make the mirror-image of the Ryugu samples' transoceanic trek since Japan is due a fraction of the Bennu material in exchange. Just how much rock that will turn out to be is a mystery until the capsule's return. But when the spacecraft executed the sampling maneuver, mission personnel estimated that it might have grabbed as much as 4.4 pounds (2 kilograms) of Bennu rocks — far more than Hayabusa2 was able to bring back.

This time, NASA personnel intend to make the trip. "Instead of them coming to pick up the sample, we will bring it to them unless they want to come over to pick the sample up," Nakamura-Messenger said, although she won't escort the samples herself, since she retired from NASA in late March.

But even without chaperoning space rocks across the ocean herself, taking part in the sample exchange was an important moment for her, particularly since the Hayabusa missions are beloved in Japan. Because Japan doesn't permit dual citizenship, Nakamura-Messenger gave up her citizenship to join NASA.

"Of course, I wanted to be a NASA scientist, that's why I came to the United States, but it was a little bit hard for me to give up my own identity," she said. Her mother told her it was worth it, saying, "You're still Japanese inside of you," she recalled.

"I'm protecting the sample for the United States and Japan at the same time," she said. "That I was still able to be involved in my mother nation's space mission as a NASA employee was a huge, huge deal."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.