There's Something Weird About the Craters of Asteroid Ryugu

The Japanese mission Hayabusa2 just bid farewell to the asteroid the probe spent a year and a half studying, and scientists have now announced some intriguing trends they noticed in the spacecraft's photos.

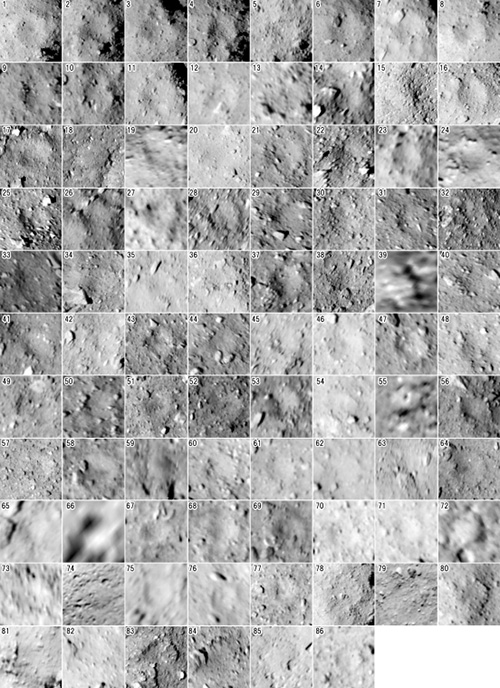

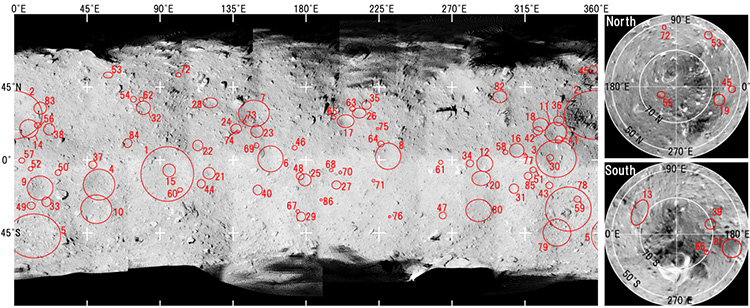

Those trends had to do with the craters dotting the surface of the asteroid, dubbed Ryugu. The team used 340 different images of the space rock's surface and identified a total of 77 craters scattered over Ryugu, each measuring at least 66 feet (20 meters) across. But those pockmarks aren't distributed as evenly across the surface as the scientists might have expected, the researchers explained in a new paper.

Instead, the craters are clustered in a couple of different ways. There are more craters near the equator than the poles, the scientists found, and there are more on the eastern side of Ryugu than on the western. Additionally, the scientists didn't find as many relatively smaller craters within this size range as they might have expected given the number of very large craters the space rock sports.

Related: Look Out Below! Japan's Hayabusa2 Drops Target Markers on Asteroid Ryugu

Those patterns became particularly clear when the team looked at particularly large craters, the 11 that measure at least 328 feet (100 m) across. (That collection includes Ryugu's largest crater, Urashima, which is about one-third of the asteroid's diameter.)

Of those 11 monster craters, five line up along the ridge ringing the asteroid's equator. That's more than twice as many as the team would have expected if Ryugu's craters were distributed randomly, the researchers said.

The discrepancies don't mean that the solar system has been targeting this one unremarkable space rock, of course. Instead, the team said that the clustering of craters is a result of the asteroid's geological history.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers said that most of the equatorial ridge is relatively old but the westernmost part is younger. That would explain why the craters are unevenly distributed: The rest of the ridge has had much more time to pick up these impact scars.

The scientists hope that when they analyze the samples from Ryugu now on their way back to Earth, it could better inform these theories about how the asteroid came to be the way it is now, a university statement about the project said. Those samples are due to land near the end of next year.

The research is described in a paper being published next spring in the journal Icarus.

- Watch Japan's Hayabusa2 Grab a Piece of an Asteroid in This Incredible Video!

- Shadow Selfie! Japanese Asteroid Probe Snaps Amazing Post-Landing Pic

- Japan's Hopping Rovers Capture Amazing Views of Asteroid Ryugu (Video)

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.