Meet the 17-year-old who discovered an alien planet: A Q&A with high school student Wolf Cukier

"I never expected it to get this big."

17-year-old high school student Wolf Cukier made a major discovery on the third day of his NASA internship, when he noticed the telltale signs of a distant planet orbiting two stars.

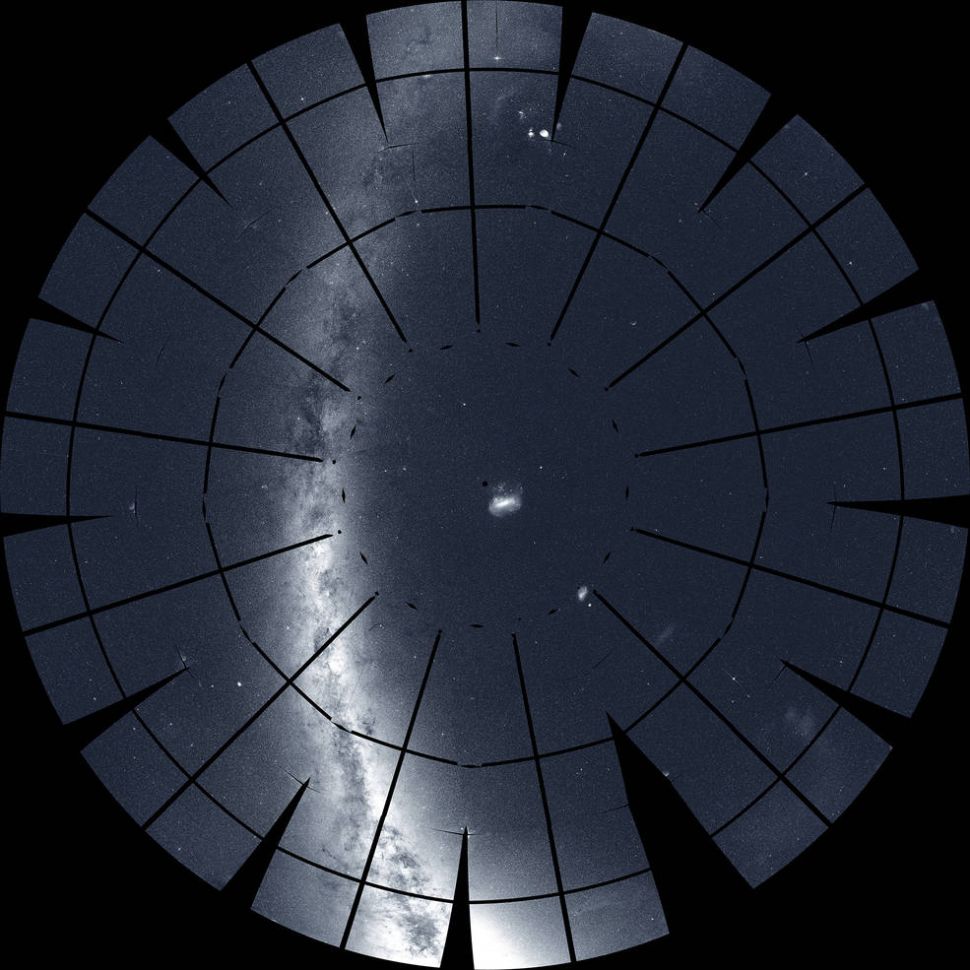

Cukier was viewing data from exoplanet TOI 1338 b, a Saturn-size gas planet that travels in a circumbinary orbit, or around two stars, 1,300 light-years away from our sun, in the constellation Pictor. Cukier spotted the planet using data from NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS), which is tasked with detecting distant planets by spotting when the light from their stellar parents dim as the exoplanets travel in front of the stars, as seen from our perspective. The student's observations mark the first detection of a planet around two stars using TESS data.

Space.com had an opportunity to interview Cukier and hear him share this wonderful story. In speaking with Space.com, the teenager also opened up about how the media attention has made him feel, as well as how young STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) enthusiasts can push through the ''noes'' until they get a ''yes.''

Related: NASA's TESS exoplanet-hunting mission in pictures

Space.com: Have you always been fascinated with astronomy or science in general?

Wolf Cukier: I've probably always been interested in science. My mom is trained as a geologist. She passed that love of science down to me … when I was in middle school, whenever we would get on a plane to go somewhere, my mom would get me a science magazine to read, and I think reading those helped pique my interest even more in science and, in particular, astronomy. And [science] just kind of always has been interesting to me.

Space.com: What kind of science magazines were you reading?

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Cukier: I think, usually, like a Scientific American and occasionally National Geographic. [I leaned more] towards the sciency articles in that.

Space.com: When did you know that you wanted to apply for the NASA internship? Can you describe a little bit of what they were proposing to have you do for the internship?

Cukier: As part of my school, I signed up for the science research program, which basically provides a support structure for kids interested in doing research to find a mentor in order to start doing research. So, as part of this program, students are required to find a mentor, like an actual trained scientist or engineer in the field that they're interested in to provide a project and help them through it.

So in order to continue in this program, to do research, I sent emails to various researchers in my field [of interest] throughout the country, and eventually I found someone who referred me to Ravi [Kopparapu, Research Scientist at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center] who was my mentor for the summer of 2018 at NASA. And then, this past summer, I was invited back, but Ravi had other travel stuff he had to do. So I worked with Veselin Kostov [Research Scientist at NASA GSFC, SETI Institute] this past summer, [when] the goal was to find one of these planets. And we just happened to find one pretty quickly.

Space.com: Can you talk a little bit more about how the high school mentorship program led to the NASA internship? Did one of your supervisors at the high school have a list of contacts? When you say ''in your field,'' do you mean astronomy or a specific interest (like exoplanet studies) within astronomy?

Cukier: I was specifically looking towards astrobiology. My teachers didn't have a list. They just had a knowledge of what other students in the past [had done] that worked and how to properly send emails, etc., and also how to read the scientific articles, [which is] necessary in order to understand the field.

Space.com: So you looked for people who are experts in astrobiology and then you reached out to them?

Cukier: Yes. So I actually found on my [search] a list of grant recipients, with all their emails. That's what I used as a starting point.

Space.com: And so then, how was that first internship (the 2018 internship) different from the one you did the year after?

Cukier: The 2018 internship was more theoretical astronomy; so it [involved] trying to calculate the Goldilocks, or habitable, zone around binary star systems. So I was updating the climate model that Ravi Kopparapu, my mentor, had already used to develop the single-star habitable zones. And through updating that model, I was able to use it to calculate a habitable zone for planets orbiting two stars.

Space.com: The light curves of stars and star systems dip when there is a transit of a planet or the smaller star. Can you describe what was it [was] about this light curve that caught your attention?

Cukier: I was looking for a circumbinary planet. When we have a binary star and some planet around it, stars generally exhibit (if the planet's such that we would be able to detect it) a phenomenon called an eclipsing binary. So what that is is the series of alternating, or generally alternating, dips [in the light curve].

When the light from the big star is blocked by the light of the small star, there's a large dip. And when the small star is blocked by the big star, there is a small dip. So [when there is also] a planet, we generally see the transit when the planet blocks some of the big star's light. So this planetary transit can look surprisingly similar to the secondary eclipse, because it's a small thing blocking, like, a bright star … They can sometimes look similar, and they did in this case.

I was looking at data from the Planet Hunters TESS citizen science project … it's a project where ordinary people are able to log on to their computers from home and help scientists find planets and classify star systems that TESS has been observing.

I was looking through everything that a citizen scientist — any citizen scientist — had flagged as being an eclipsing binary … so going through this has the benefit of it narrow[ing down] my field of search to only two-star systems or generally two-star systems. There may be a couple of false positives in there, but that doesn't really matter.

But there's one trade-off in that it only shows a small segment of the data at once to the citizen scientists, and therefore, I was only able to see a small segment of data from each star. So when I stumbled upon the light curve of what would later be named TOI 1338, I saw a big primary eclipse and almost immediately after — like a day or two [later] — there was a small dip, which I thought was a secondary eclipse...

And when I looked at the full data for the system, the predicted location of the secondary eclipse was not where the small dip on the data I was looking at was. It was about four days later.

So, the fact that the small dip I saw in the data did not match the predicted [dip], based on all the data, meant that what I was looking at was very likely not the secondary eclipse. It was something a lot more interesting than that, and it turned out to be a planet.

Space.com: When you made this realization, what was the next step?

Cukier: My next step was to bring it to my mentor's attention. So it was on like Day 3 of my internship, about Day 1 [or] Day 2 of actually looking through data, and so I was just going through flagging everything that looked somewhat interesting. So I had a spreadsheet of about 100 different targets that my mentor, [Kostov], and I would later look through. But this one was by far the most interesting target.

There were about 10 asterisks next to it on my spreadsheet.

I was looking through the data with Veselin, and we noticed that there was another transit … another dip in the data. And then we looked at an even more complete version of the data from the stars, and we noticed the third transit.

So, having three transits, that was sufficient in order to actually deem it worthy of further study, because we're able to actually make predictions or reasonably gain confidence off three things.

Related: NASA's exoplanet-hunting TESS space telescope moonlights in studying stars

Space.com: Talk to me about the experience of being a part of this very public, very popular scientific news story.

Cukier: It's a bit intimidating. And overwhelming. It's kind of weird. I went to the store the other day, and the cashier asked me, ''Were you on the news?'' and [I answered], ''Yes I was!'' That's not an exchange I expected … I never expected it to get this big. I just didn't expect to be recognized as, ''oh, you had your face on the news."

Space.com: Have you shared these feelings with one of your mentors at NASA or your parents? It seems like something that is very unusual for a young person to be on the news as often as you have.

Cukier: Yeah, we're all kind of surprised and overwhelmed at how much this has been taking off. But it is good for science outreach and education to continue doing this.

Space.com: Have you already started the college application process? What are you imagining for your future?

Cukier: I don't know exactly what my future will entail. Research is a very significant possibility. I currently have applications pending at a few colleges. My top three choices are Princeton and Stanford and MIT [the Massachusetts Institute of Technology] ... They all have slightly different pros and cons, and I still need to decide — first I need to get in! I need to decide which ones best suit my interests.

Space.com: What would you say to someone who is maybe a few years younger than you and may be feeling some trepidation about applying to positions at really big places, like big internships with NASA or whatever is their dream?

Cukier: I would tell people to ask. The worst thing that can happen is you get a ''no.'' And I had no idea where I would end up when I started asking people, and I got a few ''noes.'' I got a few people who didn't respond to emails when I started reaching out for internships. And I know some people in my [high school] program got over 100 ''noes,'' but eventually they ended up with a research project that they enjoy and spend time on.

I would just tell people to reach out and don't be afraid of people saying ''no.'' People will say ''no,'' but all you need is one ''yes.''

Editor's Note: This interview was edited for clarity and length.

- An Earth-size planet in the habitable zone? New NASA discovery is one special world.

- Beyond TESS: How future exoplanet-hunters will seek out strange new worlds

- Hottest known exoplanet is so hot, it's tearing its molecules apart

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.