Of the 15 states that will be touched by the moon's dark umbral shadow on April 8, no state is perhaps more enthused at the prospect of hosting the total solar eclipse than New York.

Indeed, this will be the first time in 99 years that the path of totality will sweep across the Empire State, and the "I Love New York" campaign, used since 1977 to promote tourism in the state of New York, is going all out to attract prospective eclipse watchers from other parts of the country to "Come for the Eclipse, Stay for New York."

The "Big Apple" was sliced in half

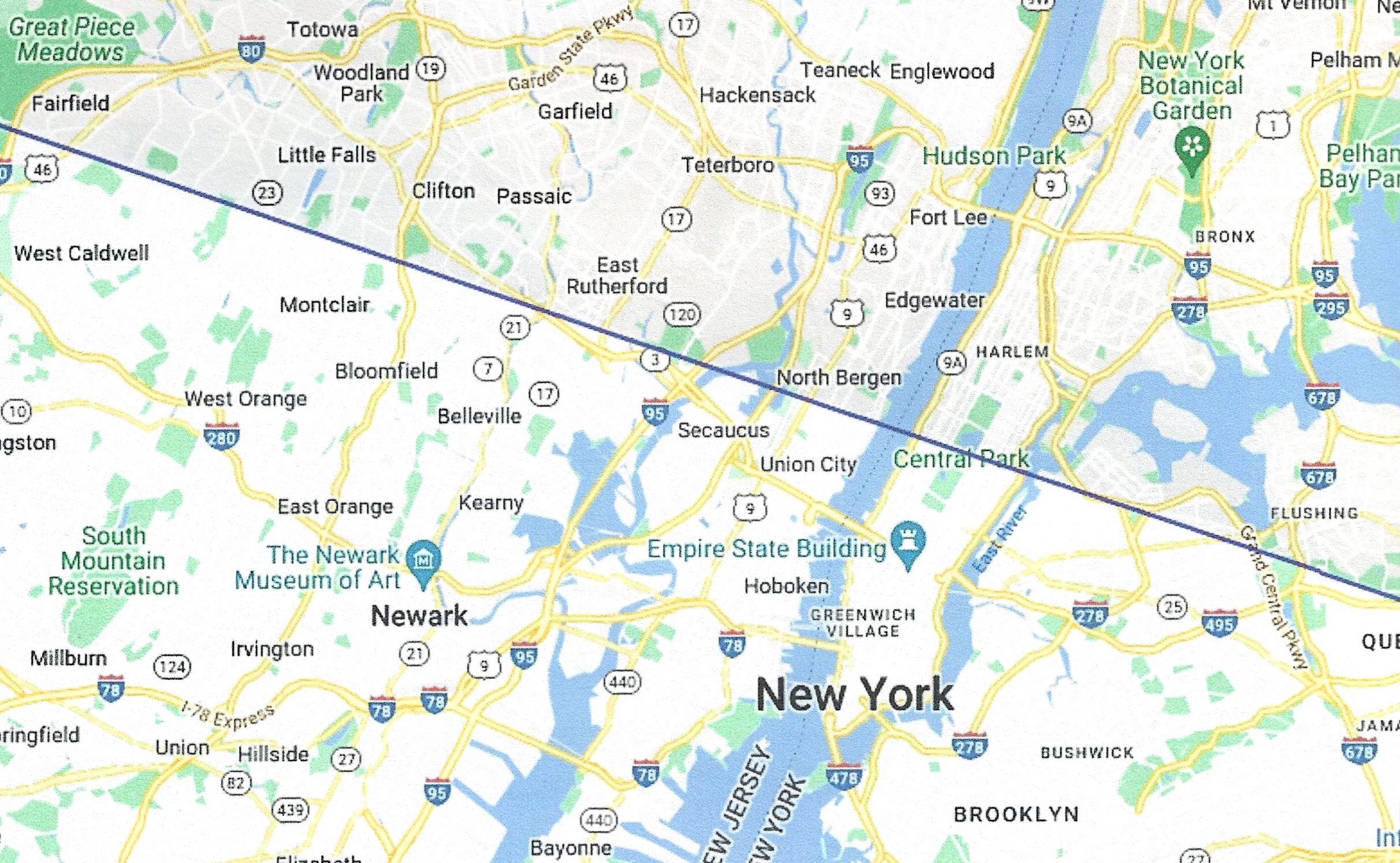

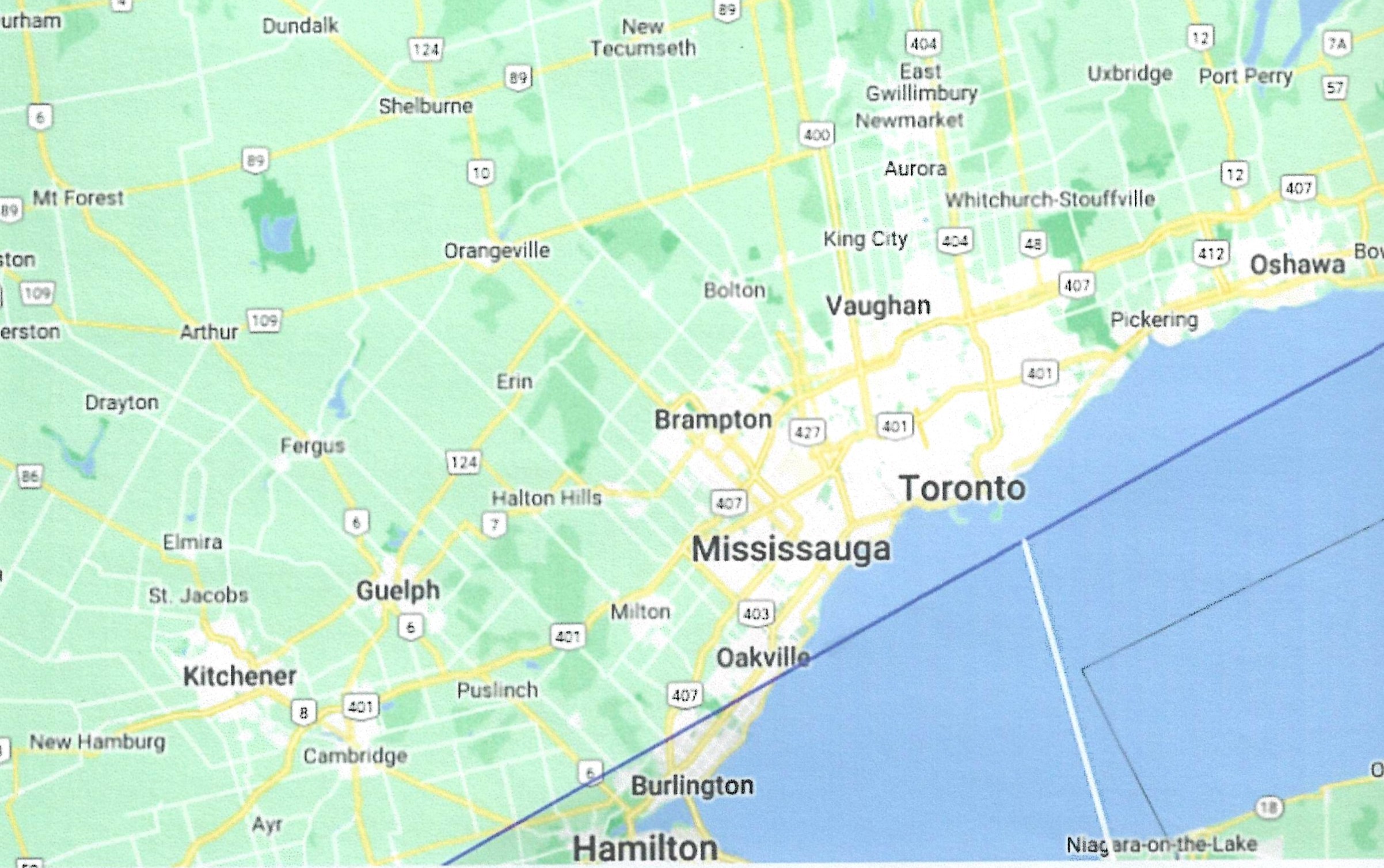

At New York's last total eclipse, which occurred on Jan. 24, 1925, totality passed over cities that again will be in the totality zone this year: Niagara Falls, Buffalo and Rochester. But unlike this year, the moon's dark shadow took a more southeasterly track in 1925 encompassing a section of New York City's metropolitan area.

To some, this is known as "The 96th Street Eclipse," since the southern edge of the totality path paralleled 96th Street in upper Manhattan.

Those to the north, including all of the Bronx and the Hudson Valley, saw a total eclipse, while south of 96th Street (Midtown and lower Manhattan, the Battery, Brooklyn and New York Harbor), saw a partial eclipse. In these areas, however, the corona was still briefly visible since the eclipse missed being total by a mere fraction of a percent. The predicted northern edge of totality went through Providence, Rhode Island.

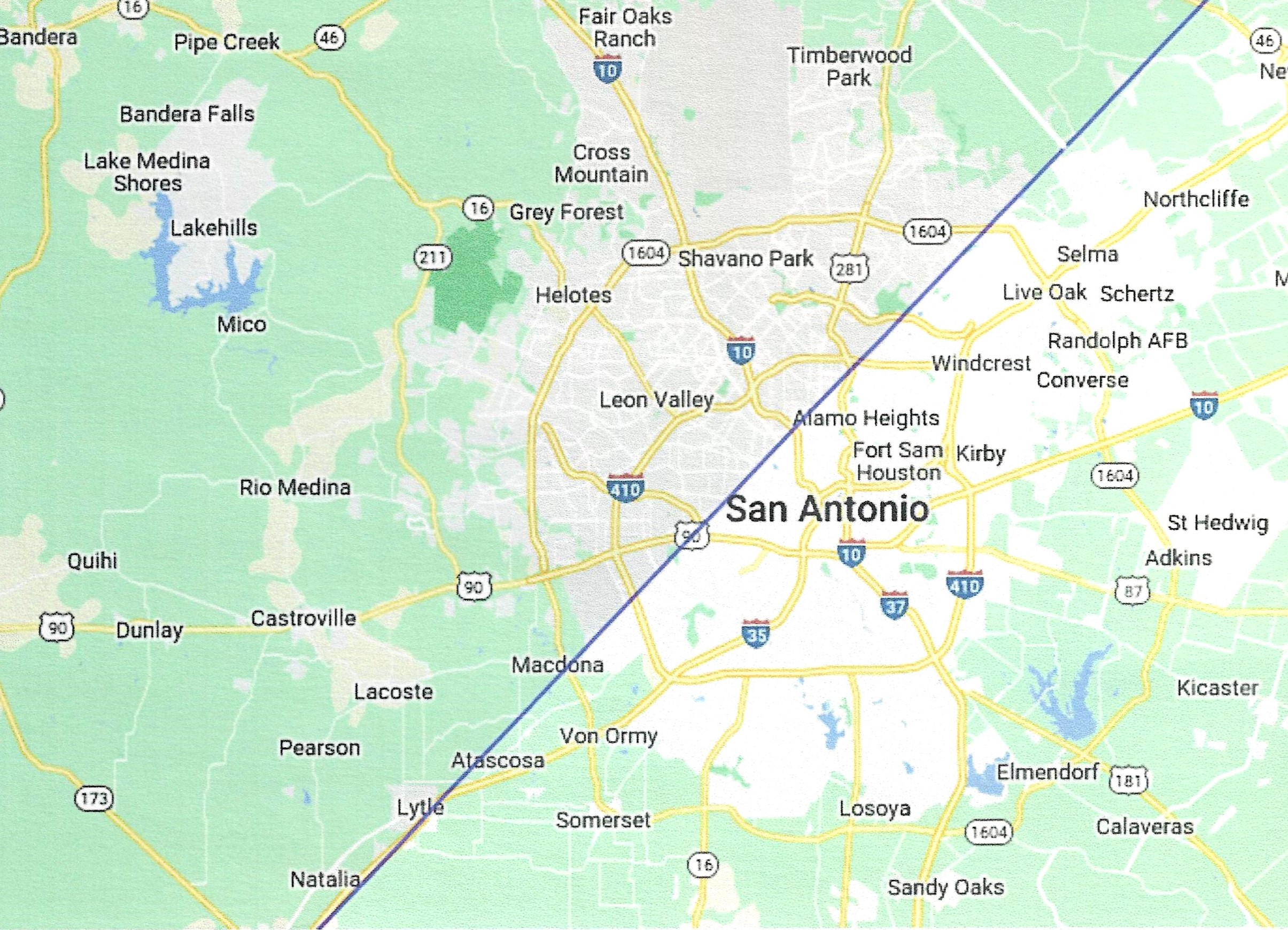

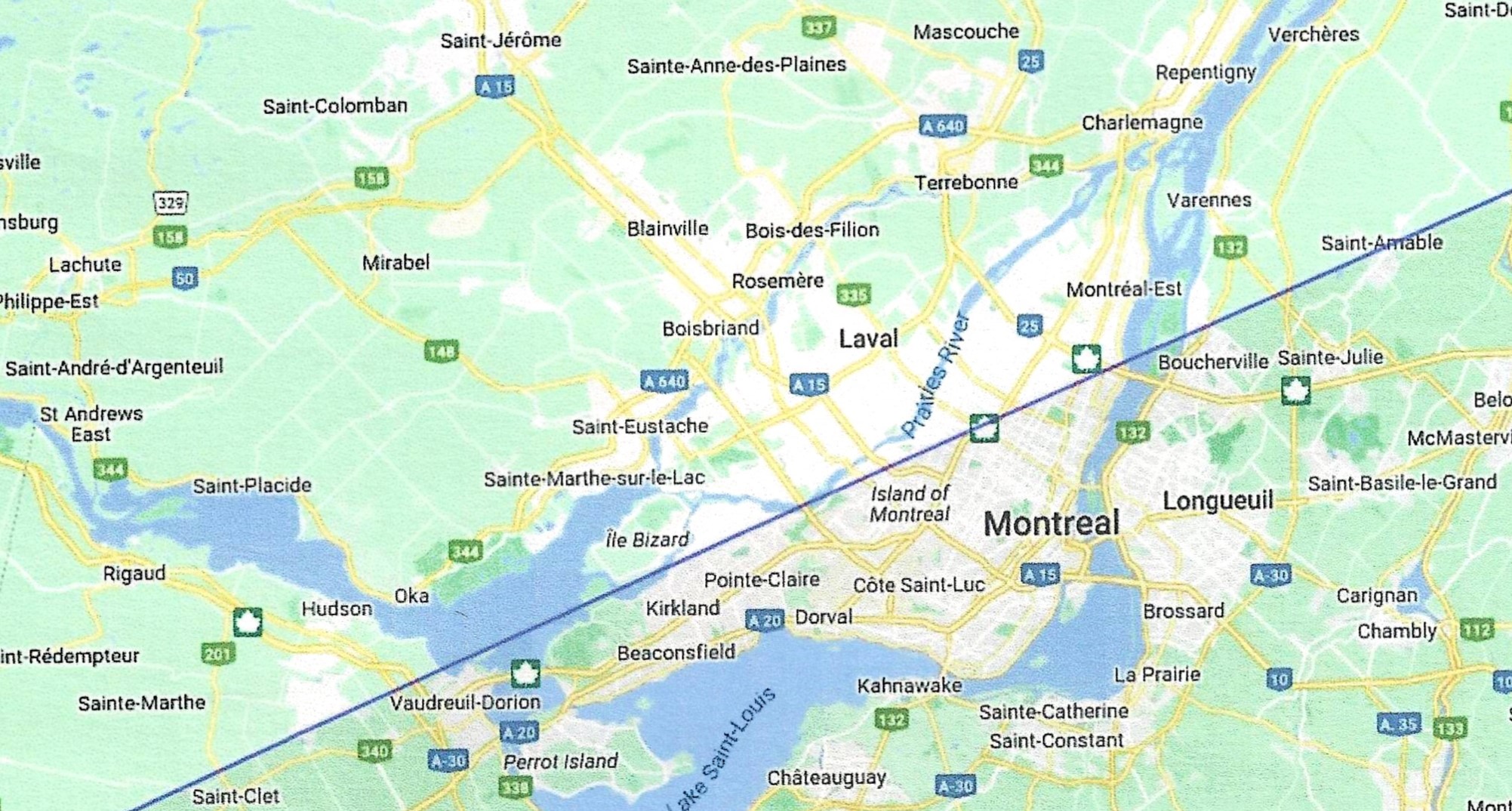

Interestingly, for our upcoming eclipse, there will be cities that will be similarly "cut in half" by the moon's dark shadow, such as San Antonio and Montreal

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

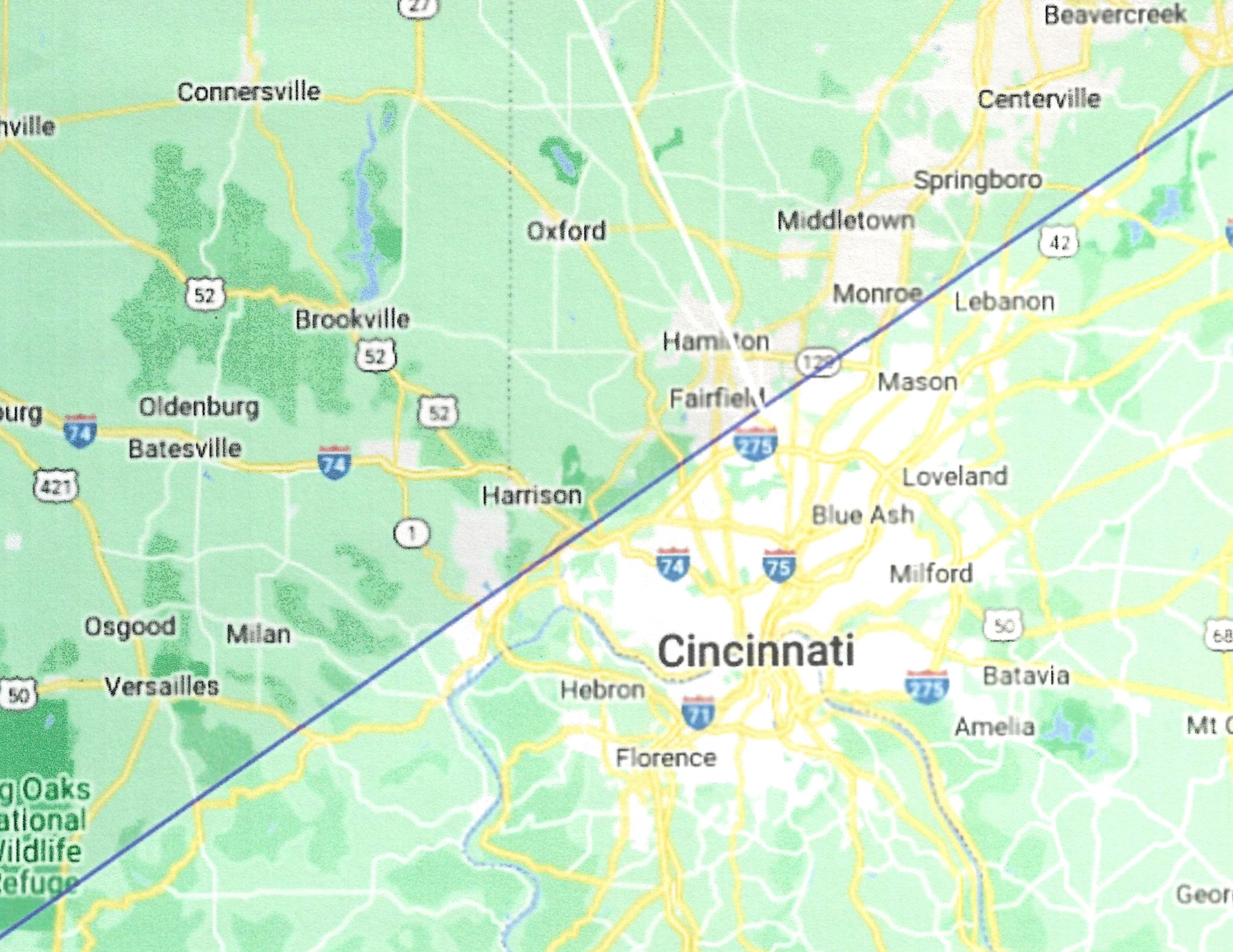

While other large metropolitan areas such as Cincinnati and Toronto will lie just outside the totality zone.

Will the corona be evident for these places as it was in 1925 outside of totality for parts of New York?

Views from the edge

Keep up to date with the latest eclipse content on our eclipse live blog and watch all the total eclipse action unfold live here on Space.com.

Seemingly supporting this idea, is that during the total eclipse of March 7, 1970, an amateur astronomer stationed at Chatham, Massachusetts, which was roughly 4 miles (7 km) outside totality, reported to Sky & Telescope magazine, that he ". . . was able to see the corona for a few seconds," using a 4-inch Schiefspiegler reflecting telescope.

Other observations in 1970 that were made near the edge of the path of totality, showed that certain phenomena, such as Baily's beads, the flash spectrum and shadow bands, persisted for at least 10 times their duration as seen from the center line of totality. Baily's beads, for instance, lasted for nearly a minute before the start of totality and for a similar interval at the end. The ruby red chromosphere remained visible throughout totality. The corona was seen before the sun was completely eclipsed and, even at the limit of the moon's shadow, the corona may have been visible for a minute or two more.

The diamond ring was born

The 1925 eclipse also gave birth to the now oft-used term "diamond ring effect." On the front page of the Jan. 25 edition of The New York Times, it was noted that: "A thin, luminous ring, set with a great gem of soft-burning light, hung in the eastern sky yesterday morning . . . while most of New York's population of six million gazed at it. For several seconds the jewel sparkled with a pure and mild radiance, then trembled and melted into the circle of light which rimmed the inky black disk of the moon. The total eclipse had come."

It appears that those who were just outside of totality had a protracted view of "the great gem" which seemed to hang on for a good many seconds during the maximum phase of the eclipse. Many apparently contacted The Times afterward, to ask why the astronomers did not alert them to the possibility of seeing this beautiful product of an almost-total eclipse. The Times, in turn, asked one of America's leading astronomers, Henry Norris Russell, to provide an explanation. In the Jan. 26 edition, under the headline "Scientists Missed Sun's 'Diamond Ring,'" we read in part:

". . . spontaneously called 'the diamond ring' by numbers of observers in New York, and this term, hitherto unknown to astronomy, was apparently fixed forever as a technical term in the literature of the subject by Saturday night."

Eclipse justice meted out

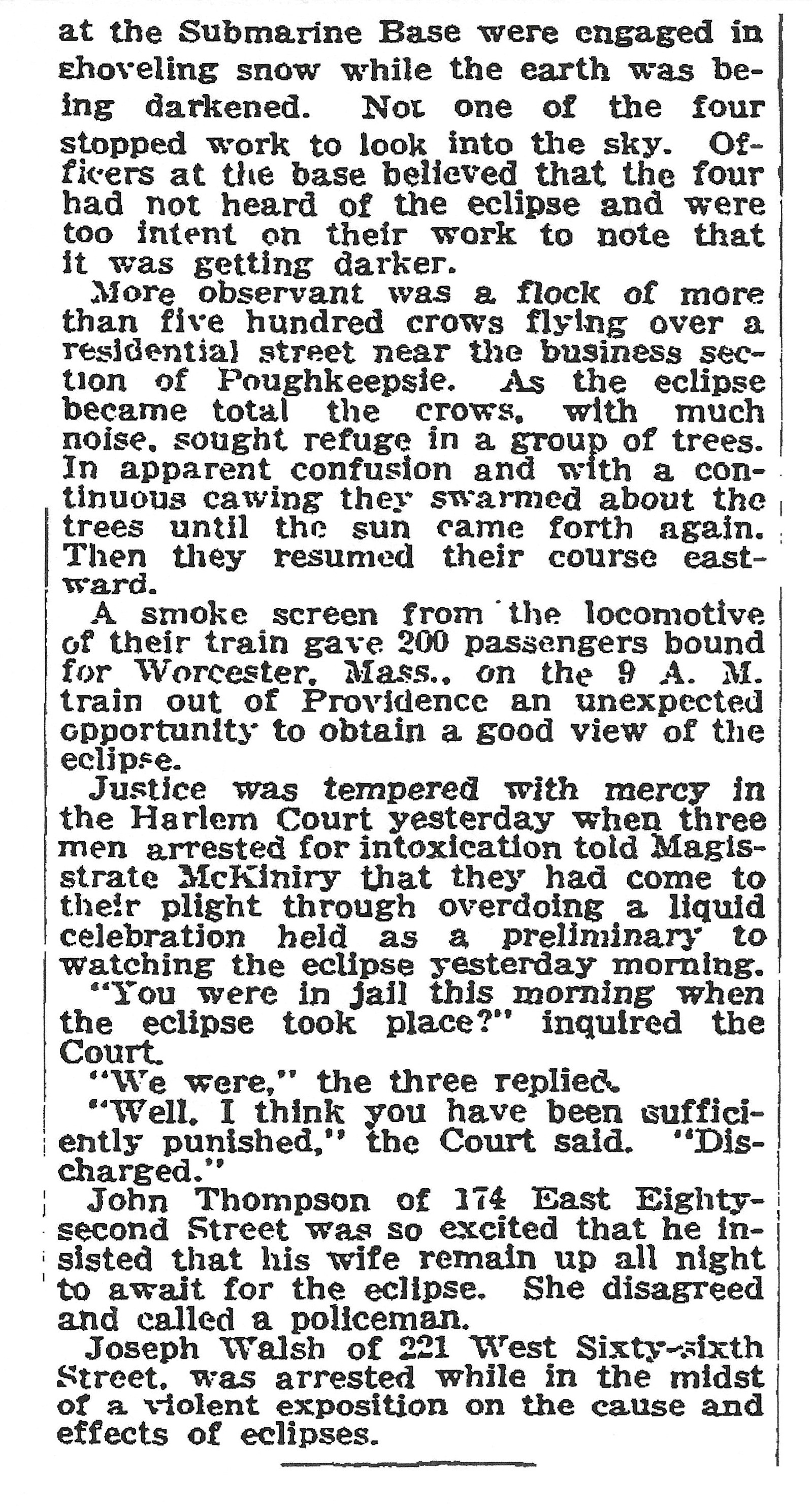

A final anecdote regarding the 1925 eclipse in New York City involved a rather unusual court case that was tried in a courtroom on the Upper East Side of Manhattan (Harlem) on the same day as the eclipse. It seems that on the night before the eclipse, three men were arrested and thrown in jail for apparently causing a ruckus thanks to the fact that they were drunk.

According to The New York Times, ". . . they had come to their plight through overdoing a liquid celebration held as a preliminary to watching the eclipse."

The three men were brought before City Magistrate Richard F. McKiniry on the same afternoon following the eclipse.

"You were in jail this morning when the eclipse took place?" inquired Judge McKiniry.

"We were," the three replied.

"Well, I think you have been sufficiently punished," Judge McKiniry said. "Discharged."

In his 1950 obituary, The Times noted that Judge McKiniry "Enjoyed a reputation for understanding human nature and for equanimity. He had a distaste for the purely legalistic in court, preferring the spirit of the law."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.