The UAE wants to rewrite what we know about weather on Mars

A nagging problem with planets is that they are just so large: Send a spacecraft to one patch of a planet and inevitably, some of the things you learn will apply only right there.

That struggle is particularly difficult when scientists ponder a planet's atmosphere and weather. By definition, these are global phenomena, and they interact with other global phenomena in intricate ways.

That conundrum is why, despite a rich history of spacecraft observations of Mars, scientists are still puzzling over how the planet's atmosphere really works — from top to bottom, pole to pole, and dawn to dusk and back again.

Related: Mars 'Hope': UAE's 1st interplanetary spacecraft aims to make history

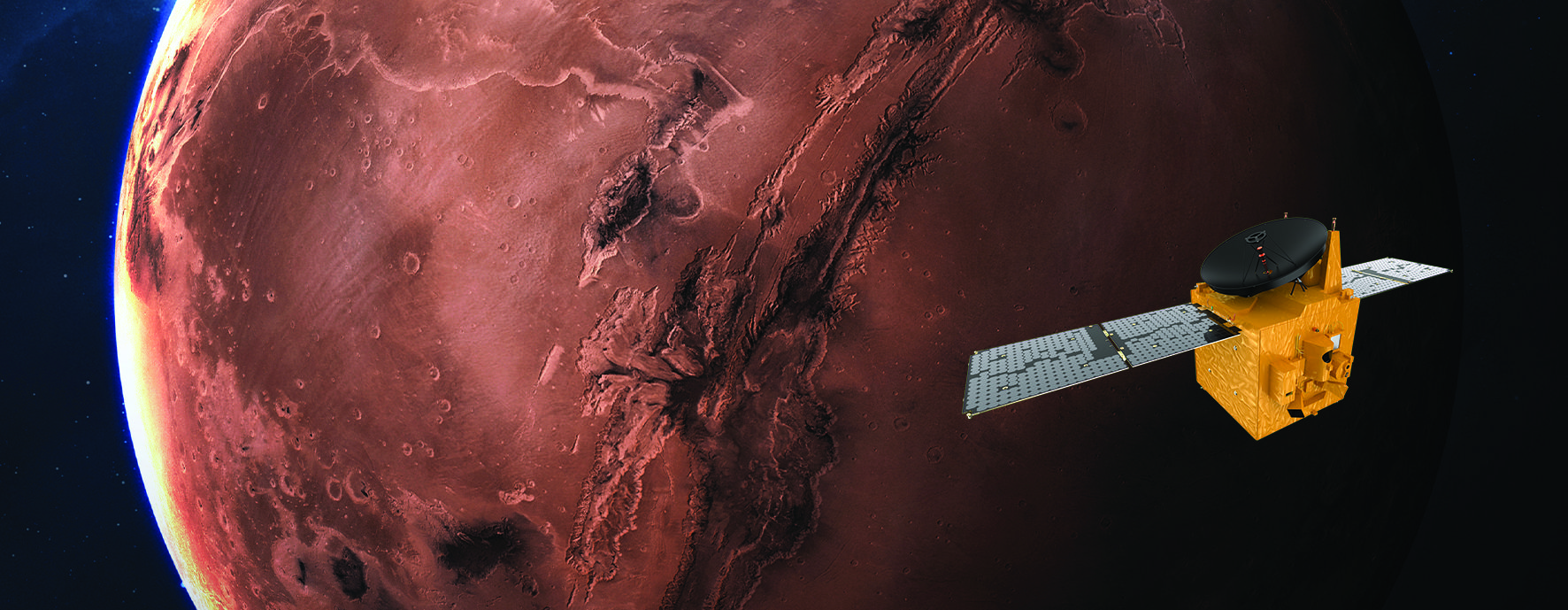

If all goes well, a mission from a country that's a newcomer to planetary science will soon begin to gather the data scientists need for a truly global understanding of the Martian atmosphere. The United Arab Emirates (UAE) plans to launch its first interplanetary spacecraft, called the Emirates Mars Mission or Hope, on Tuesday (July 14), with liftoff scheduled for 4:51 p.m. EDT (2051 GMT).

Then, the $200 million mission will embark on a seven-month cruise to Mars, slipping into orbit around the Red Planet in early 2021. Hope is scheduled to observe Mars for at least a full Martian year (a bit less than two Earth years) as it works to understand the Martian atmosphere.

If the spacecraft successfully arrives — which the team well knows is a difficult proposition — the UAE will become the fifth or sixth entity to orbit Mars, depending on how the mission's timeline compares with that of China's Tianwen-1 Mars lander, also launching this summer.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Building on the human legacy of Mars exploration

A dozen orbiters have worked at Mars before, and Hope was purposefully designed with an eye to the half-century-long history of spacecraft sent to Mars. Nevertheless, mission personnel wanted to avoid the risk of staying within the limits of what other projects have done.

"We always learn from previous missions," Mariam Al Shamsi, director of the space science department at the UAE's Mohammed bin Rashid Space Center, which runs the Hope mission, told Space.com. "There is no perfect mission, so every mission that comes up learns from the previous missions." In the case of Hope, the mission learned particularly from NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) orbiter, scientists said.

"The science of the mission is very complimentary to other missions that went to Mars," Hessa Al Matroushi, science data and analysis lead for the mission at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center, told Space.com. "But it complements them, it adds more understanding to the gaps that had been shown."

In order to strike that balance, the engineers-turned-scientists leading the mission needed to understand the scope of Mars exploration to date, which meant consulting the Mars science community. After that process, Hope leaders concluded that the atmosphere was the place to focus on to find that sweet spot.

Then, it was on to designing the spacecraft itself.

"You don't want to send two spacecraft that measure the same things, no matter how important they are," Bruce Jakosky, a project scientist on the Hope mission and the principal investigator of MAVEN, told Space.com. "What is new is making measurements that we just didn't realize needed to be made before, and in that sense, it builds on everything that has come before it."

In the case of Hope, mission personnel realized that by using similar instruments to those onboard MAVEN and other spacecraft, but putting the spacecraft into a completely unique orbit, the mission would be able to tackle some crucial questions about the Martian atmosphere.

An atmosphere of Hope

The Hope spacecraft carries three instruments: ultraviolet and infrared spectrometers, plus an imager sensitive to optical and ultraviolet light. Those instruments are packed onto a spacecraft that clocks in at 3,000 lbs. (1,350 kilograms) and will require about seven months to get to Mars, where it will focus on the Red Planet's thin, carbon dioxide-dominated atmosphere.

Although scientists have gotten atmospheric data from a host of spacecraft before, Hope brings something new to the table: it orbits over the planet's equator. "Our uniqueness comes from the orbit," Al Shamsi said. That orbit is what gives the spacecraft its ability to see how conditions in the lower atmosphere change over time on Mars.

"What this mission does is, it provides us a full understanding of the Martian atmosphere throughout the day," Sarah Al Amiri, science lead for the mission and the UAE's minister of state for advanced sciences, said during a news conference held on July 9. "So it covers all regions of Mars at all local times at Mars, and that's a comprehensive understanding that fills in the gap of changes through time through different seasons of Mars throughout an entire year."

But Hope will study the whole atmosphere, not just the lower atmosphere, where weather unfolds. In particular, it will help scientists understand what takes place in a layer called the thermosphere, which lies between the upper and lower atmosphere, about 60 to 120 miles (100 to 200 kilometers) up. Here, the gas is influenced by what's happening both near the surface of Mars and in the upper atmosphere.

"The thermosphere, it's kind of the transition point between the upper atmosphere and the lower atmosphere," Fatma Lootah, manager for Hope instrument science, told Space.com. "So it's very interesting to look into what's happening there." In particular, the scientists want Hope's data to help them connect what happens in the upper and lower atmospheres, rather than looking at the layers in isolation.

More science potential

that if the spacecraft beats the odds and successfully makes it to the Red Planet, it will aid plenty of other research as well.

Some of that is built into the mission's primary goals. For example, Hope's orbit will also position the spacecraft to regularly photograph the fuzzy bubble of hydrogen wisping out from the planet. MAVEN spotted that structure as it was arriving, but couldn't image the bubble regularly.

"These pictures, they're very cool to look at," Lootah said. "They're like a glowing kind of halo around the planet. So they're very beautiful to see, and I'm really excited to see these images come through."

Those images could also help scientists understand how Mars is losing its atmosphere. Once, before the Red Planet was quite so red, it had a thick, wet atmosphere like Earth's, but now it's gone. And still, the atmosphere slowly slips away from the planet's gravitational tug, drifting off into space to form that halo.

And, of course, there's the usual fact of science: that even the best scientists can't predict a planet's intricacies. "Every mission, every new instrument we've flown, has discovered things that we didn't know even to ask about," Jakosky said. "You design a mission to make measurements to answer some specific questions, and you design the instruments so that they can make the measurements you're looking to get. With most science missions, and certainly with the Mars missions all the way back to the beginning, I think everybody would be disappointed if that's all we got."

One potential opportunity for those surprise discoveries is from random events like dust storms. "I think also the most exciting thing is when you get something interesting in the data that you didn't expect, and we call them episodic events," Lootah said. "That's very exciting to see, and since it's going to cover a huge amount of the planet, we'll be able to see more episodic events. So that's also something to look forward to."

Even the data that scientists expect to see will end up supporting discoveries beyond the confines of the Hope mission itself, Al Matroushi emphasized, saying that the UAE purposefully decided to make all of Hope's data available to the public for just this reason.

"The mission was developed for our objectives, but the data can be used to answer a lot of science questions," she said. "I would be very pleased and excited to see what kind of science researchers will be able to get out of the data that the mission will provide."

But more than that, the Hope scientists are looking forward simply to being able to work with data from their own spacecraft for the first time after years of practicing on data from other missions and hypothetical data, Lootah said. "I think it's just going to be a surreal feeling."

That's also why the July 14 launch isn't the main event for the team. "I think people are excited for the launch, and we all are," Al Matroushi said. But launch pales in comparison to arrival at Mars in February 2021. "Seeing the first picture from the probe, that would be the most exciting moment, because this is where our work begins."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

-

Geomartian Built by the UAE and launched by the Japanese.Reply

The communications antenna is pretty robust and stiff for just communications. Usually a collapsible/foldable circular array is used. This looks more like a precision fire control radar rather than a communications antenna.

The optical systems on board should work quite well for acquiring a target.

It looks like it will be placed into a picket orbit of the Martian Moons around the Martian equator. Any probes landing and taking off from Phobos or Deimos will have someone looking over their shoulder.

A sample return mission from the Martian Moons is relatively easy. Phobos appears to be material accreted from meteor and asteroid impacts on Mars. A sample return mission from Phobos would be a very deep embarrassment to Houston’s fake planetary geology. A few dozen zircons from Mars would destroy Nasa’s fictional narrative of a long dead Mars. The correct narrative being a Mars recently murdered (geologically recent) by an interstellar asteroid.

This looks more like a search and destroy mission rather than a scientific mission. Nothing about this mission looks that special. It looks like a kludged design meant to prevent any sample return from Mars. It might also be there to sabotage any probe looking at anything that Houston does not want found (geology or physics, not aliens).

Phobos/Grunt was sabotaged and now it looks like the Chinese probe is about to get Houston’s special attention.

“Knowing that a trap exists is the first step in avoiding it” – Frank Herbert, Dune.

If the Chinese probe had sensors to detect that it was being painted by Hope’s “communication” antenna that would be a dead giveaway of Hope’s actual intended use. -

Edward Vix Geomartian, there are great prices at GoodRx for necessary medication, thought I'd mention it as it would appear some important ones might need refilling.Reply -

Geomartian Reply

Edward Vix said:Geomartian, there are great prices at GoodRx for necessary medication, thought I'd mention it as it would appear some important ones might need refilling.

Are you in this picture?