A Mars 'Hope': The UAE's 1st interplanetary spacecraft aims to make history at Red Planet

"If a small nation like us is able to achieve this kind of mission and get ourselves to Mars, then everything is possible."

Next week, the United Arab Emirates will launch its first-ever interplanetary mission, a Mars orbiter that the nation hopes will inspire the region and advance Red Planet science.

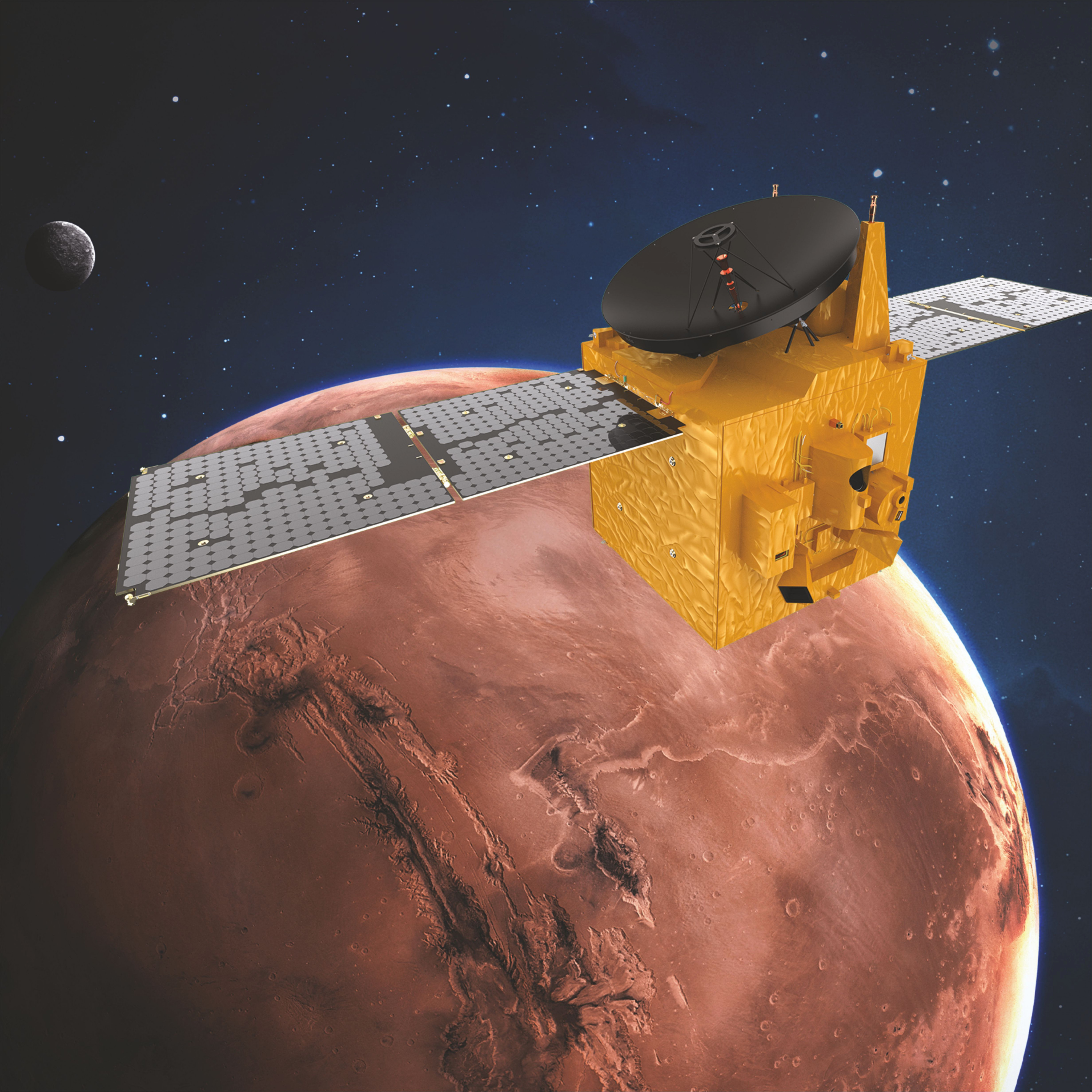

The mission, called Hope or the Emirates Mars Mission, is designed to spend one Martian year, or about two Earth years, studying the thin Martian atmosphere. Mission personnel hope that the spacecraft's results will teach scientists something new about the Red Planet's past and present atmosphere — and perhaps even help humans keep our own planet's atmosphere from becoming its twin. But the mission is also an ambitious step for a country not yet 50 years old that reached space for the first time only in 2009.

"I think one of the messages of this mission is hope, which is the name of the probe itself," Hessa Al Matroushi, science data and analysis lead for the mission at the UAE's Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Center, told Space.com. "If a small nation like us is able to achieve this kind of mission and get ourselves to Mars, then everything is possible."

Related: Meet Hope: The UAE's first spacecraft bound for Mars is now complete

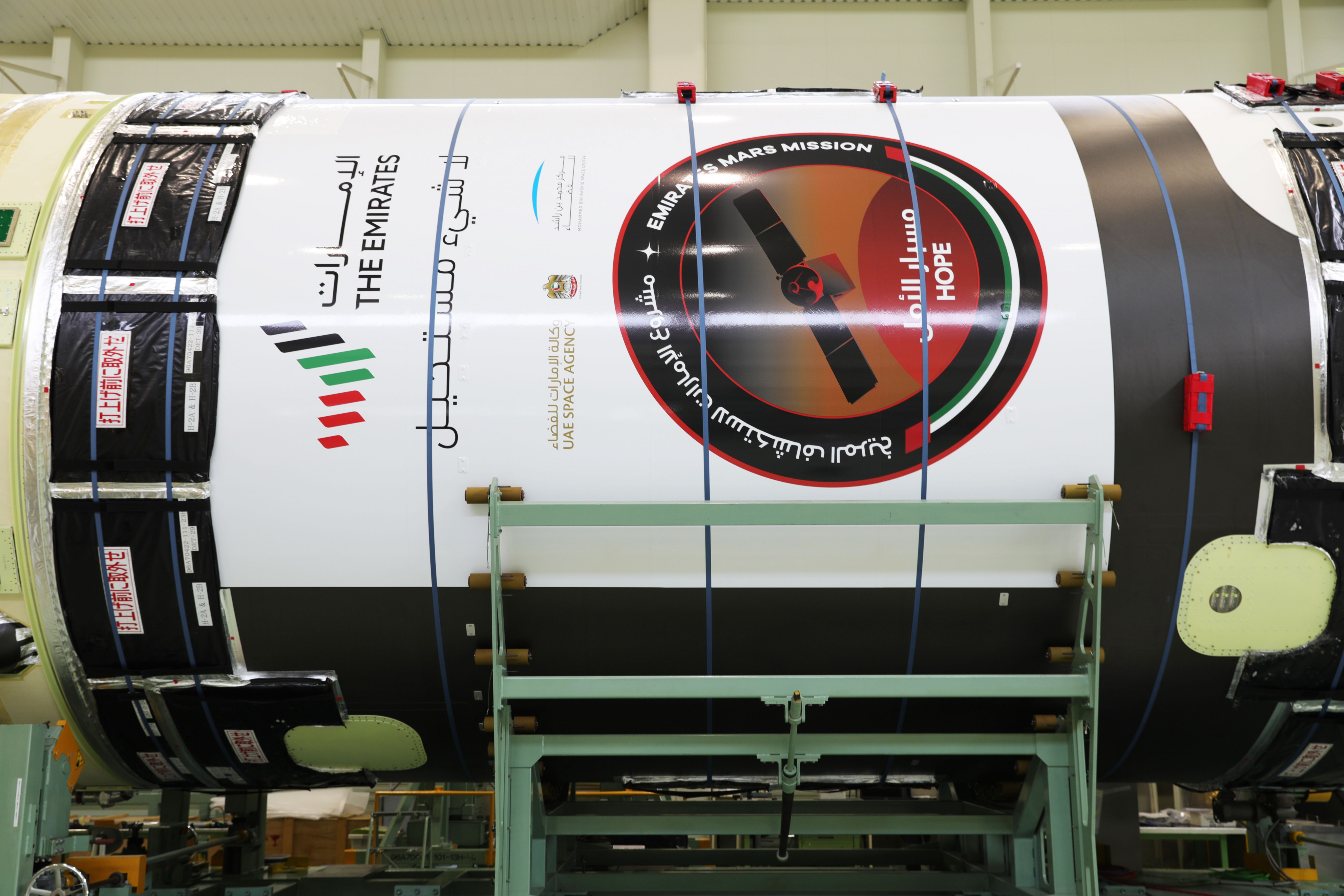

Now, that satellite is tucked into the nosecone of a Japanese H-2A rocket at the Tanegashima Space Center in Japan, awaiting its moment to leap from Earth. Launch is currently scheduled for 5:51 a.m. local time on July 15 (4:51 p.m. EDT or 2051 GMT July 14).

The $200 million Hope mission was always designed to make that sort of larger statement both at home and abroad. The decision to go to Mars was meant to jolt the nation's technology industry and create a planetary science community where essentially none existed. The mission would pose a host of challenges, known and unknown, and be the first time an Arab country reached for another planet.

And everything would need to happen fast, much more quickly than a traditional Mars mission might. UAE leadership began floating the idea of sending an orbiter to Mars in 2014. And they had a deadline: arrival at Mars before December 2021, the nation's 50th anniversary. Because of the finicky orbital mechanics of reaching our neighbor, that meant blasting off this summer — and if the spacecraft misses its window, it will need to wait 26 months to try again.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team was asked to tap international expertise and domestically build a spacecraft that could conduct new science at Mars on that timeframe. That meant mission personnel needed not only to manage the engineering challenges of spaceflight, but also to become part of the international community of Mars scientists. They needed to be familiar enough with the history of Mars exploration to identify what projects might be scientifically promising.

"We don't want to have these massive amounts of data and nobody's interested in it," Fatma Lootah, manager for Hope instrument science, told Space.com. "We want this data to be novel, this data to be breakthrough."

The team decided to focus on the atmosphere of Mars, which probes have studied before but not comprehensively. By putting Hope into an orbit no spacecraft has used at Mars, the mission will be able to study the upper and lower atmosphere simultaneously, allowing scientists to better understand how they interact. The unique orbit will also give scientists the first detailed understanding of Mars weather at large: across the globe, throughout the day and over the full seasonal cycle.

The team also needed to be pragmatic enough to choose something feasible on the assigned timeline, and to bring in colleagues who could make that schedule more manageable. One such partnership was with the University of Colorado at Boulder's Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics, which houses the science team of NASA's Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission, which has been orbiting Mars since 2014 studying a different set of atmospheric questions.

That mission's principal investigator, Bruce Jakosky, said that working as project scientist on Hope has been a very different experience from his time on NASA missions. "One is very aware [while] working on this of the international collaboration. That's new," he told Space.com. "We're working hand in hand with the Emiratis on this, and that really brings a different perspective to how one approaches a mission."

Jakosky said that for Hope, mission work wasn't just about the mission itself, it was about the international stage. "The UAE today doesn't have a strong science background. I will point out it did 1,000 years ago, they were the leaders in the world and I see this as an opportunity for them to regain some of that stature," he said. "It is a big step to take to do a Mars mission. Historically more have failed than have succeeded."

Since the UAE began its space program, it has considered spaceflight to be about more than just getting a piece of metal and electronics into space. The country has built itself on oil revenue but knows that income is unstable and wants to diversify. Some of the motivation for a Mars mission was that such a project would force developments in technology and other non-oil sectors.

"If you deliver something that works in space and is capable of performing tasks in space, it sends also a strong message about the quality of work you do within your country," Omran Sharaf, mission lead for the Hope spacecraft, told Space.com earlier this spring of the UAE's decision to build its first fully domestic satellite, KhalifaSat, which launched in 2018.

But while the UAE wants to make a statement, the scientists on the Hope mission are here to do science.

"When this [mission] was announced, a lot of people were like, 'Oh, they're just doing it for show,'" Lootah said. "It's not for that at all; it's for the greater good. This novel science that's going to come out, the data, this is going to further humanity's knowledge of another planet, the most similar planet to Earth we know of right now. So I think I want to focus on the science."

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her on Twitter @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.

-

Hammer Good luck to any and all who try. I'd rather see attempts made to the outer system and icy moons.Reply -

Lovethrust Reply

I would too but that would be way too big of a first step! Remember the US out of all the spacefaring nations is the only one to make it too Jupiter and beyond...Hammer said:Good luck to any and all who try. I'd rather see attempts made to the outer system and icy moons. -

Hammer Reply

Thanks for bringing that up. I've never really thought about it before, we ARE the only country that has been to the outers.Lovethrust said:I would too but that would be way too big of a first step! Remember the US out of all the spacefaring nations is the only one to make it too Jupiter and beyond...