The United Arab Emirates' Hope mission to Mars in photos

The UAE's first interplanetary mission

The United Arab Emirates' Hope mission, which arrived at Mars on Feb. 9, 2021, will conduct a detailed examination of the Martian atmosphere.

Also known as the Emirates Mars Mission, Hope is an orbiter designed to spend one Martian year (two Earth years) looking at the Red Planet's atmosphere, studying how it eroded over time until Mars no longer was able to host liquid water on the surface.

Click through this Space.com gallery to learn about why the Arab country embarked on such a bold mission, and what this will mean for the country's science, engineering and education communities.

Full story: Welcome to Mars! UAE's Hope probe enters orbit around Red Planet.

Hope mission personnel celebrate the receipt of signal confirming the spacecraft arrived in orbit around Mars on Feb. 9, 2020.

With the successful Mars orbit insertion, the UAE becomes the fifth entity to reach the Red Planet, joining NASA, the Soviet Union, the European Space Agency and India.

Full story: Welcome to Mars! UAE's Hope probe enters orbit around Red Planet.

Engineering pride

Technicians are shown here working on the Hope mission at the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre in Dubai.

Going to Mars was meant to spur the nation's technology industry to great heights, and also to create a planetary science community in a region where there was practically none before the mission.

This is the first time any Arab nation has attempted a Red Planet mission, and the development happened quickly as UAE leaders first considered a Mars orbiter in 2014.

Looking at the spacecraft bus

The UAE has decided to ramp up its own spacecraft-building technologies — such as building Hope's "bus," or main structural component seen in this picture — to diversify the nation's industries.

The nation is largely built on oil revenue and is looking to create other streams of income on top of this one, and it hopes that the Mars mission would help spur technological development in other sectors, such as electronics.

Finishing touches

The nearly complete Hope Mars orbiter undergoes checks during the final launch preparations on June 6, 2020.

The team brought on international partners to help get the spacecraft ready efficiently, including the University of Colorado at Boulder's Laboratory for Atmospheric and Space Physics.

The partnership benefitted from the university's expertise on the Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution (MAVEN) mission, which is also studying the Martian atmosphere with different science questions.

Hope is ready!

Some spacecraft engineers pose before the Hope orbiter on Feb. 18, 2020. The UAE built the spacecraft domestically, while asking for international expertise to meet their goal of performing new science at Mars with their very first mission.

Personnel quickly embedded themselves in the international community of Mars scientists to get up to speed on the latest science and to pick what aspects of the planet were best worth studying.

The rocket

Hope will ride a Japanese H-2A rocket to orbit, lifting off from the Tanegashima Space Center in Japan.

This booster has already sent aloft at least one interplanetary mission — Japan's Akatsuki spacecraft, which studied the planet Venus. Other prominent missions launched on this rocket type include Selene (aka Kaguya) that studied the moon, the Ikaros solar-sailing spacecraft, and the Hayabusa 2 mission that returned a sample from the asteroid Ryugu in late 2020.

Cruising to Mars

This artist's illustration shows the Hope orbiter making its way into space on top of the H-2A rocket.

The satellite has a total mass, with fuel, of 3,300 lbs. (1,500 kilograms), according to NASA, and is about the size and weight of a small car.

The spacecraft is expected to last for at least two Earth years in Mars' orbit, but its mission can be extended to 2025 if the spacecraft remains in good health and funding is available for the mission extension.

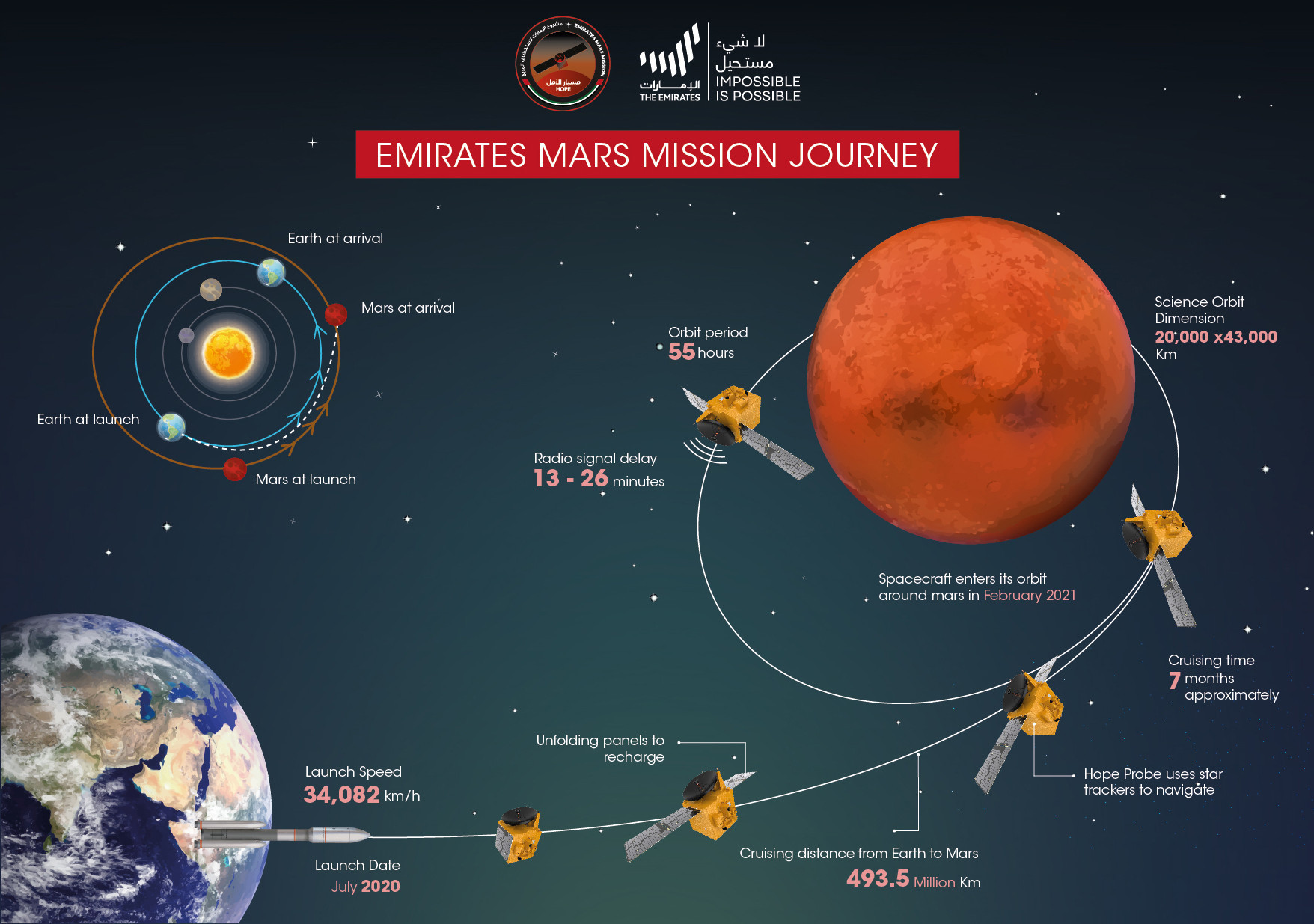

Complicated maneuvers in space

This illustration shows in detail all the mission steps required to get Hope into orbit around Mars.

Shortly after launch, it unfolded its solar panels to recharge its batteries for the trip to Mars. As Hope approached the Red Planet, it used its star trackers to navigate and to enter the correct orbit.

The final orbit will be a 55-hour-long, slightly elliptical path around Mars that measures roughly 12,500 by 26,700 miles (20,000 by 43,000 kilometers). At its widest, the orbit of Hope will be 10 times the diameter of Mars.

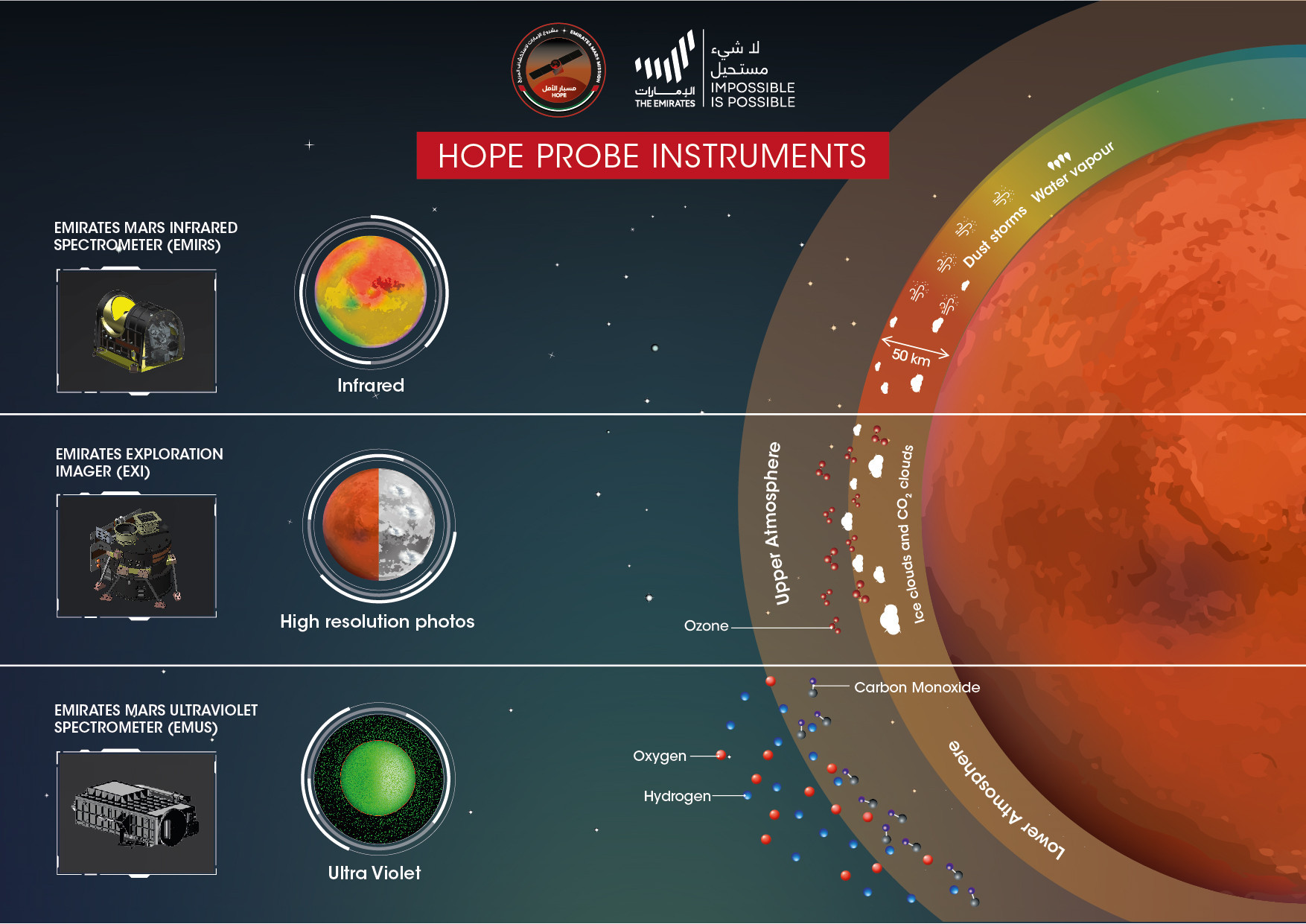

Martian instruments

There are three main instruments on the Hope orbiter:

The Emirates Mars Infrared Spectrometer (EMIRS) will look at the Martian atmosphere's dust, ice clouds, water vapor and temperature profile.

The Emirates Exploration Imager (EXI) will image the Martian atmosphere to look for dust, water ice and ozone abundance.

The Emirates Mars Ultraviolet Spectrometer (EMUS) is a spectrometer that will examine changes in the atmosphere and emissions of hydrogen, oxygen and carbon monoxide, among other things.

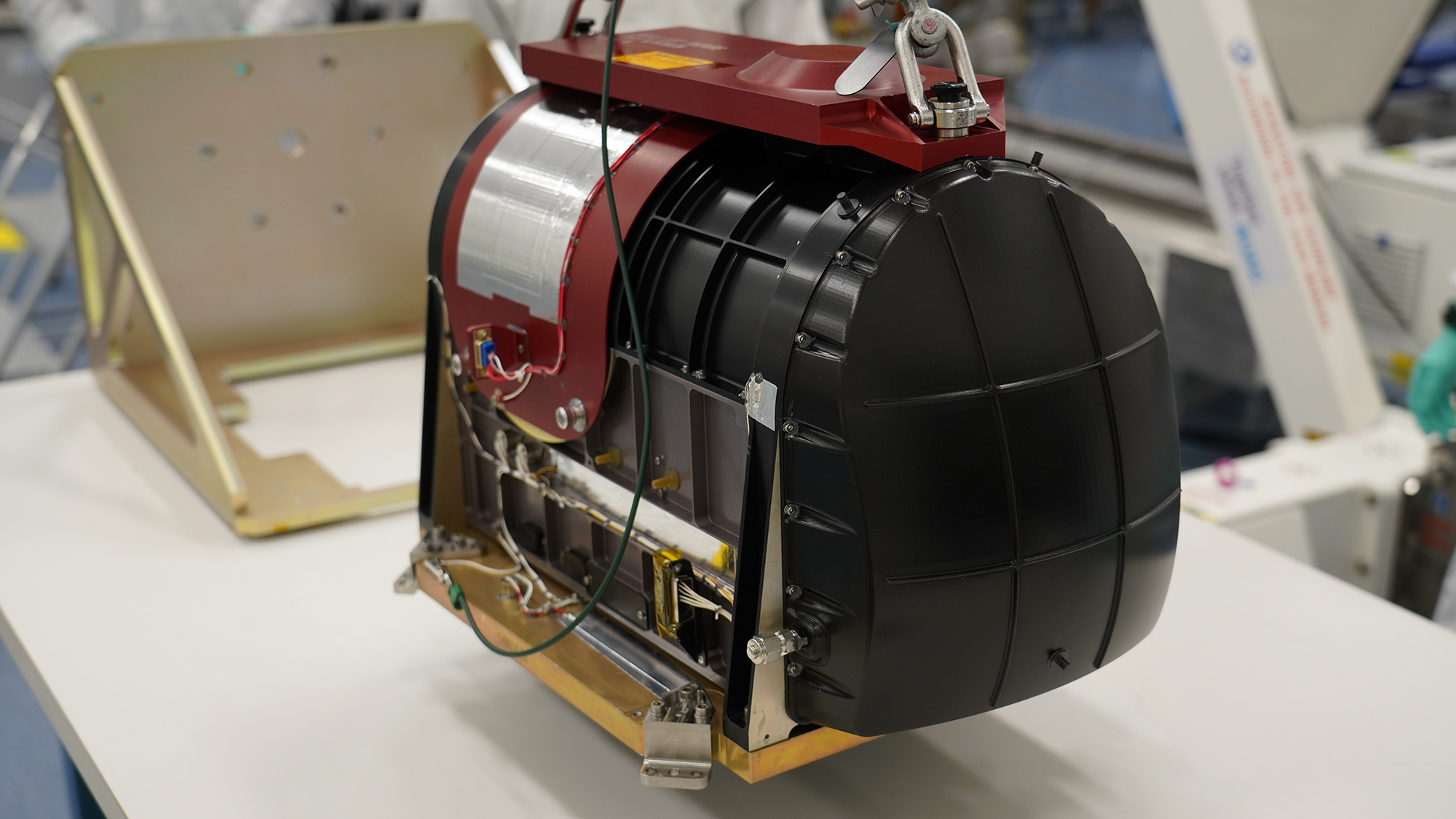

EMIRS closeup

This is a closeup of the Emirates Mars Infrared Spectrometer (EMIRS).

In collaboration with Arizona State University, the Mohammed bin Rashid Space Centre in Dubai designed EMIRS to measure the dust, ice clouds, water vapor and temperature profile of the Martian atmosphere. These observations will add on to other missions' work at the Red Planet and lead to a greater understanding of planetary atmospheres more generally.

Hope, riding aboard a a Japanese H-IIA rocket, launched successfully on July 19, 2020 from the Tanegashima Space Center in Japan. This was a historic launch for the UAE, as it is their first mission launch to Mars.

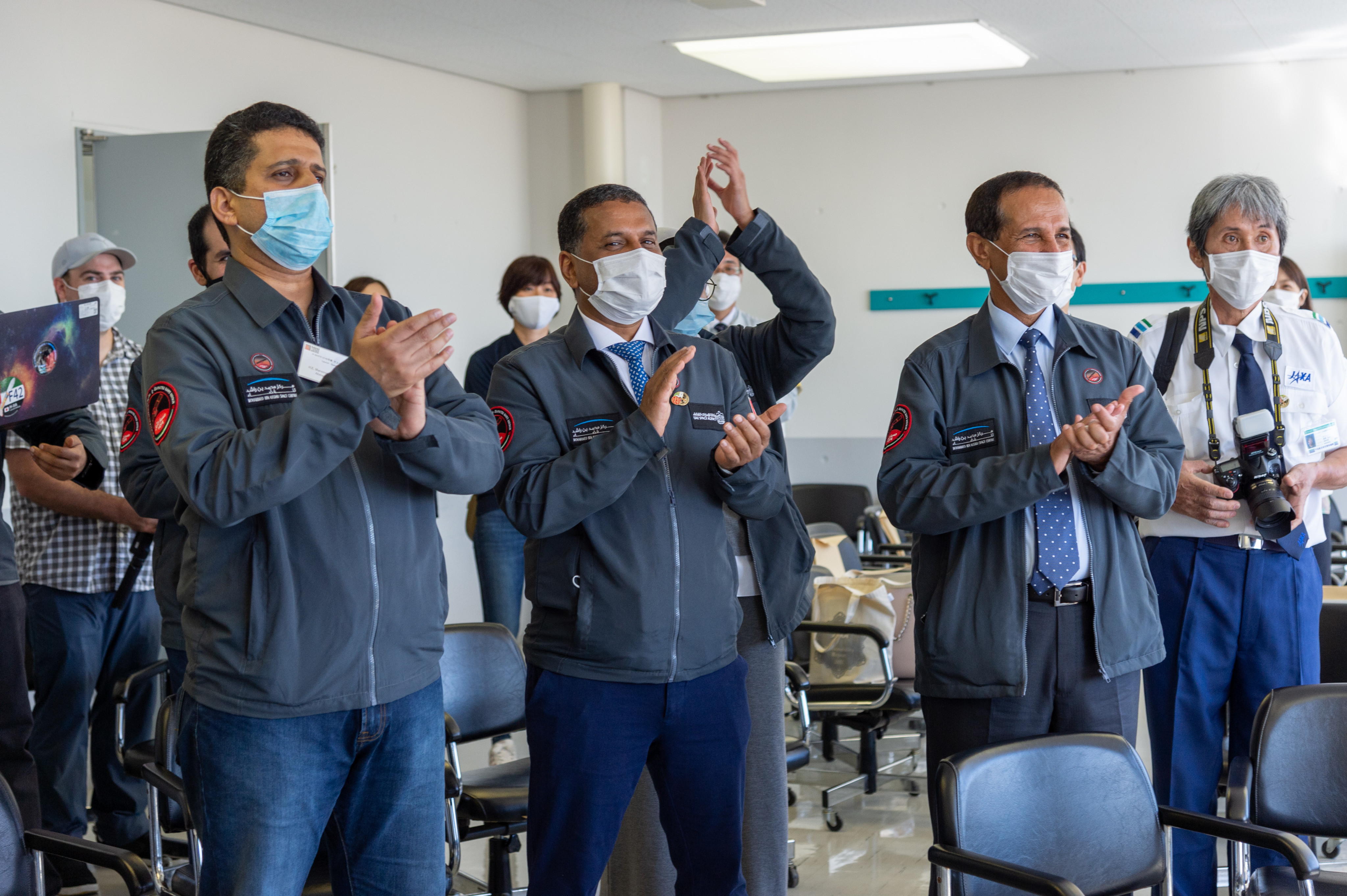

Crowds, launch technicians and official attendance were strictly limited due to the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, with everyone wearing masks to minimize the risk of transmission.

Aside from the new precautions implemented to contain the pandemic, the launch went as planned and the spacecraft successfully began its seven-month journey to Mars.

Masked officials applaud the successful launch of the United Arab Emirates' Hope mission on July 19, 2020. The masks were necessary to contain the spread of the novel coronavirus pandemic, which posed a worldwide threat that March during the last phases of launch planning. The launch, including new precautions implemented to contain the spread, was successful.

This is an image of Mars taken by the star tracker on the UAE's Hope mission in August 2020 and shared worldwide on social media. As the probe was still far away from the planet ahead of its expected February 2021 arrival, Mars appeared as a tiny dot.

"The Hope probe is officially 100 million km [60 million miles] into its journey to the Red Planet," Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, prime minister of the UAE, wrote on Twitter on Aug. 24, 2020. "Mars, as demonstrated in the image captured by the probe's star tracker, is ahead of us, leaving Saturn and Jupiter behind."

The image was shared days after the mission nailed its first major maneuver en route to the Red Planet, safely achieving a midcourse correction.

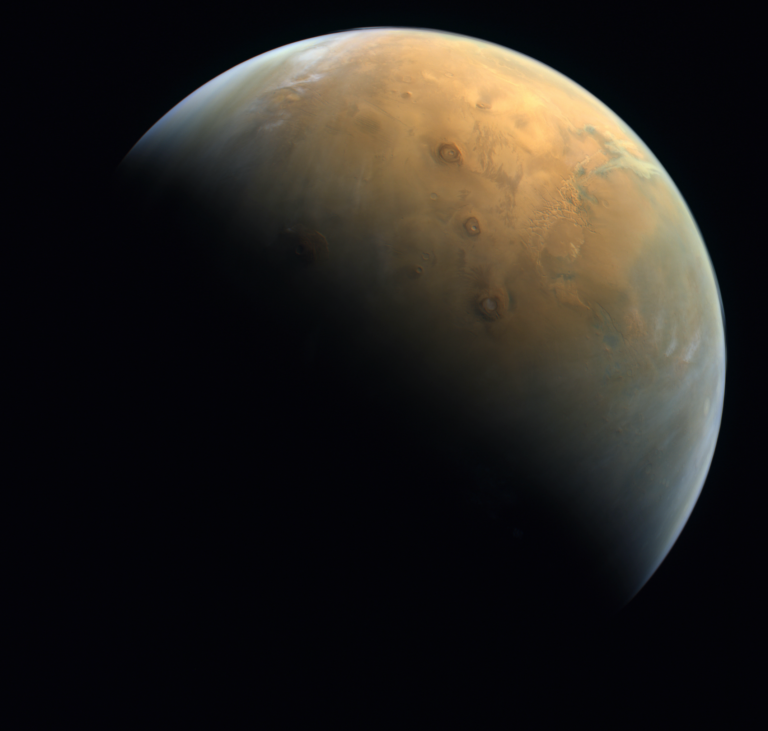

The UAE's Hope spacecraft's first photo of Mars from orbit, captured on Feb. 10, 2021.

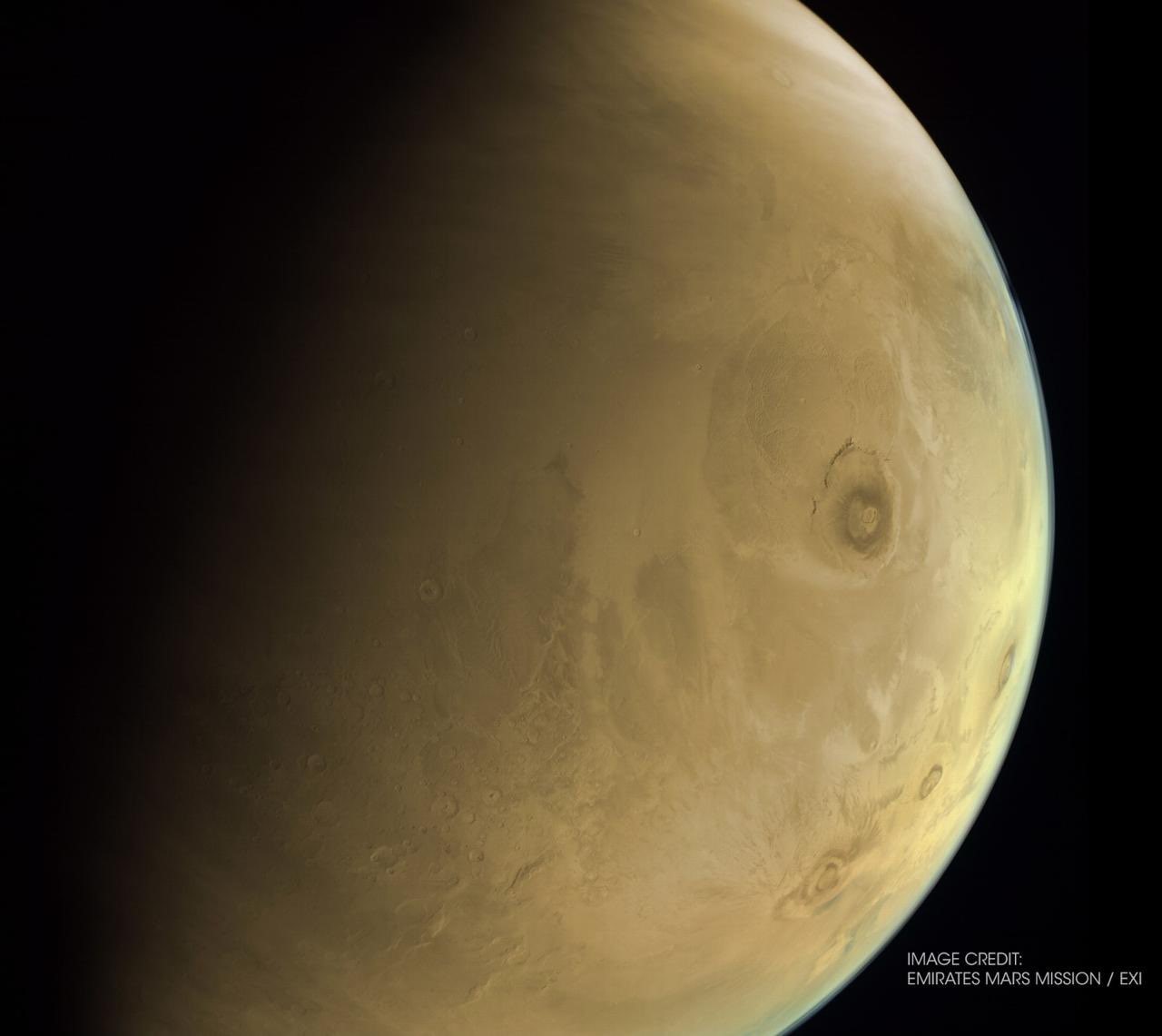

An image of Mars captured by the Hope spacecraft on Feb. 26, 2021, shows Olympus Mons, the largest volcano in the solar system.

Read more:

- A Mars 'Hope': UAE's 1st interplanetary probe will make history

- The UAE's Hope Mars orbiter: 6 things to know about the historic mission

- The boldest Mars missions of all time

Editor's note: This gallery was originally published July 15, 2020 and updated Feb. 5 and March 19, 2021.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.