Did a NASA telescope detect cosmic 'hot dogs' or Dyson spheres?

"As a mainstream WISE Team member, working on WISE-detected distant galaxies, the steady occasional reference to 'Dyson spheres' since launch has been an annoyance."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

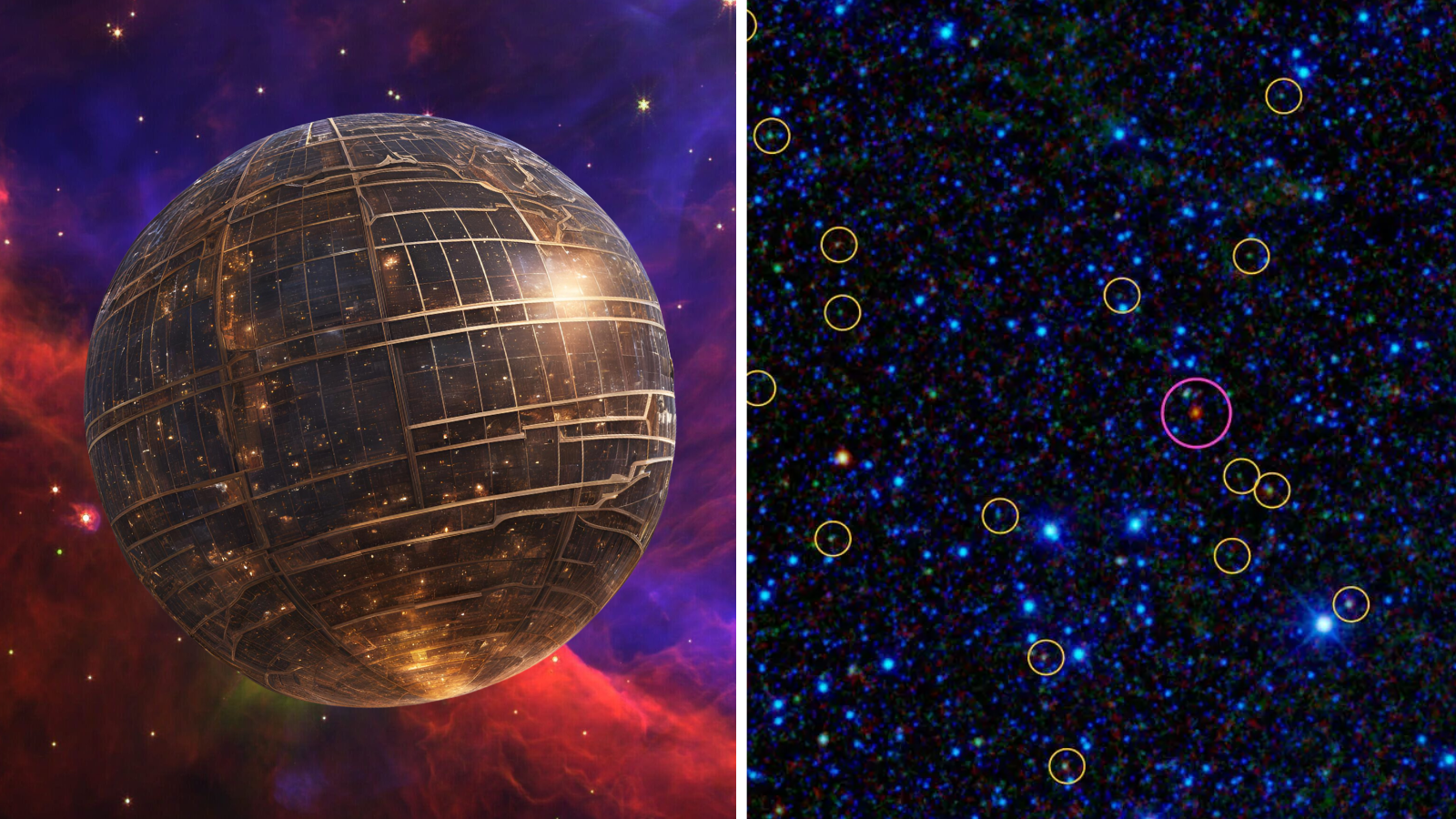

Earlier this year, scientists proposed that one of NASA's spacecraft — the Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, or WISE — may have discovered signals that could indicate the presence of megastructures used to harvest the energy of stars. These so-called "Dyson spheres" would be a sign of highly advanced civilizations capable of making major changes to their planetary systems.

Yet, not everyone was sold on these detections, and a scientist working with WISE (the spacecraft was renamed "NEOWISE" in 2013) is determined to set the record straight. He suggests the signals are far likelier to represent dusty galaxies with shrouded and ravenous black holes that are colorfully named "Hot DOGs."

"As a mainstream WISE Team member, working on WISE-detected distant galaxies, the steady occasional reference to 'Dyson spheres' since launch has been an annoyance," British astronomer and University of Leicester astronomer Andrew Blain told Space.com. "The appearance of the paper over the summer almost saying 'here they are' was finally too much!"

Dyson sphere detections get cooked

As humanity is quickly discovering, the price of being a technologically advanced civilization has to do with the huge energy demands that come with our inventions.

But the primary energy source in any planetary system is its central star, meaning that alien civilizations (if they exist, of course) could turn to their stars to siphon off the stellar energy they require directly, preventing any of this energy from leaking into space and becoming unusable.

Related: Life after stellar death? How life could arise on planets orbiting white dwarfs

A "Dyson sphere" is a hypothetical megastructure that could surround a star and directly harness its energy. This technology was first suggested by physicist Freeman Dyson in 1960. Since then, many scientists have been hunting these potential megastructures, reasoning that the detection of such a thing would constitute the discovery of a highly advanced alien race.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One potential signal from such an energy-harvesting megastructure would be the detection of excess "waste heat" in the form of infrared radiation. Indeed, the team known as Project Hephaistos searches for such signals among 5 million stars using data from WISE, the Gaia spacecraft, and other telescopes.

In May 2024, Project Hephaistos is the group that published a paper in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society (MRNAS) declaring the detection of seven unusual objects that may fit the bill. These objects resembled red dwarfs, the most common and longest-living stars in the Milky Way, but had an unusual infrared signature that didn't resemble other such stars — a signature that may indicate Dyson spheres.

That's what prompted Blain to speak up.

He warns that assuming such a signal indicates a Dyson sphere is an act that's "fraught with danger" due to potential noise associated with a large sample of stars. Even more importantly, he warns about confusion with emissions from dusty background galaxies, particularly Hot DOGs.

"The number of Hot DOGs in any patch of sky is just right to see seven in the area searched for WISE," Blain said. "And there are definitely Hot DOGs, whereas it’s not at all clear if there are Dyson spheres."

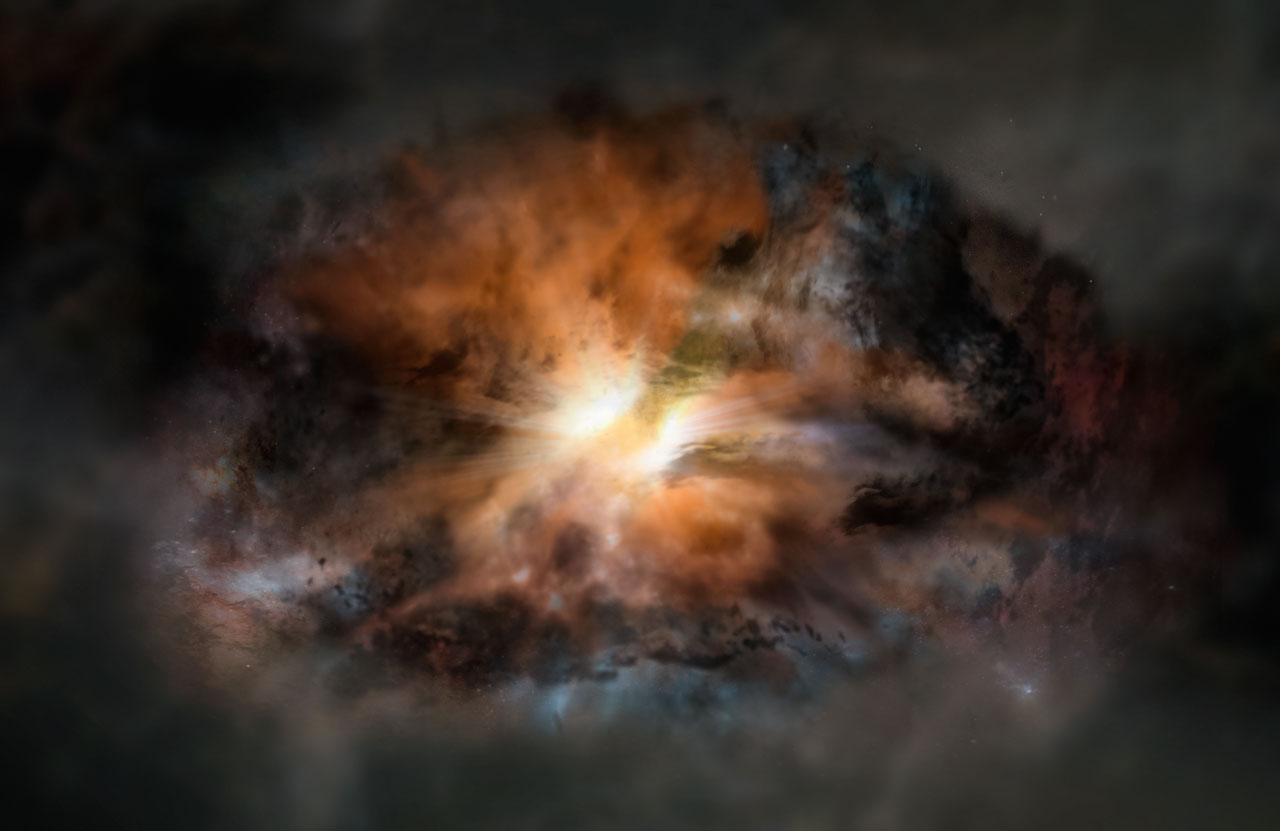

Hot DOGs or "Hot Dust-Obscured Galaxies" are very powerful galaxies with feeding supermassive black holes at their hearts. They are dark in visible light because of obscuring envelopes of dust that surround them. However, Hot DOGs are bright in infrared light, which can slip through the dust shrouds around these galaxies without being absorbed.

WISE first discovered Hot DOGs in the early 2010s. Their population includes WISE J224607.57−052635.0 (W2246-0526), which, upon its discovery in 2015, was labeled the "most luminous galaxy" ever seen.

Blain also explained why Hot DOG galaxies may have been mistaken for Dyson spheres in WISE data.

"If the Hot DOG galaxy happened to lie behind a star being sought for a 'Dyson sphere,' in the infrared, they'd look similar," he said. "With 5 million stars surveyed, finding seven Hot DOGs within an arcsecond or so in angle atop the star is just what you'd expect. We purposely didn’t look for Hot DOGs behind stars, as the star stops them being optically dark."

So, does this mean speculation about the WISE-detected Dyson spheres? Blain certainly thinks so.

"I think it's settled — there could be Dyson spheres, but it's not very likely that is what these objects are. Observations of the targets could be very useful though — as not many Hot DOGs have been studied in great detail, and the foreground star makes some observations much easier, as it can be used to correct for the atmosphere," Blain said. "Also, I realized that any bunch of aliens capable of building a Dyson sphere are also capable of hiding it by sending us a faux signal. That they could hide is the interesting thing from my perspective — so they could lurk in the cosmos, but we wouldn't be able to tell."

While some will be disappointed by the potential dismissal of Dyson sphere detections, Blain has different concerns. "I was more disappointed that WISE data would be used for such a speculative enterprise," he said.

Blain's research is published on the repository site arXiv.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.