How did the solar system form?

It's a tale with many twists and turns, and quite a bit of violence.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute, host of Ask a Spaceman and Space Radio, and author of How to Die in Space. He contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Opinions and Insights.

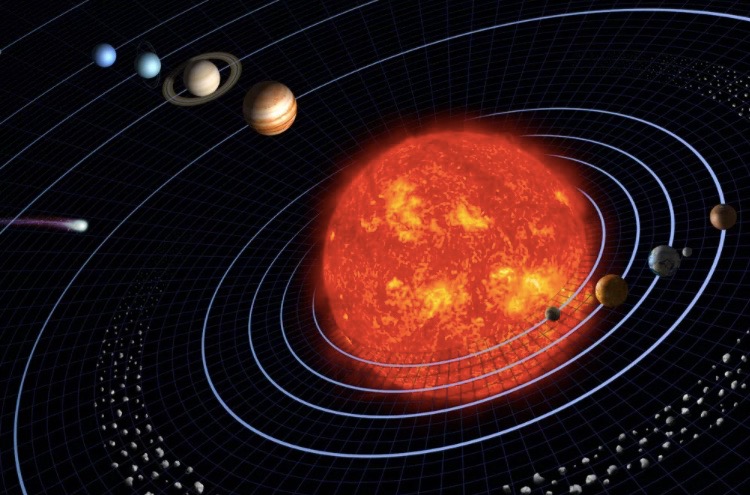

Here we are, 4.5 billion years into the lifetime of our sun, with an array of planets and smaller objects orbiting around it. How did all the planets form, and why did they end up in the orbits that they did?

The formation of the solar system is a challenging puzzle for modern astronomy and a terrific tale of extreme forces operating over immense timescales. Let's dig in.

Our solar system: A photo tour of the planets

The pre-solar nebula

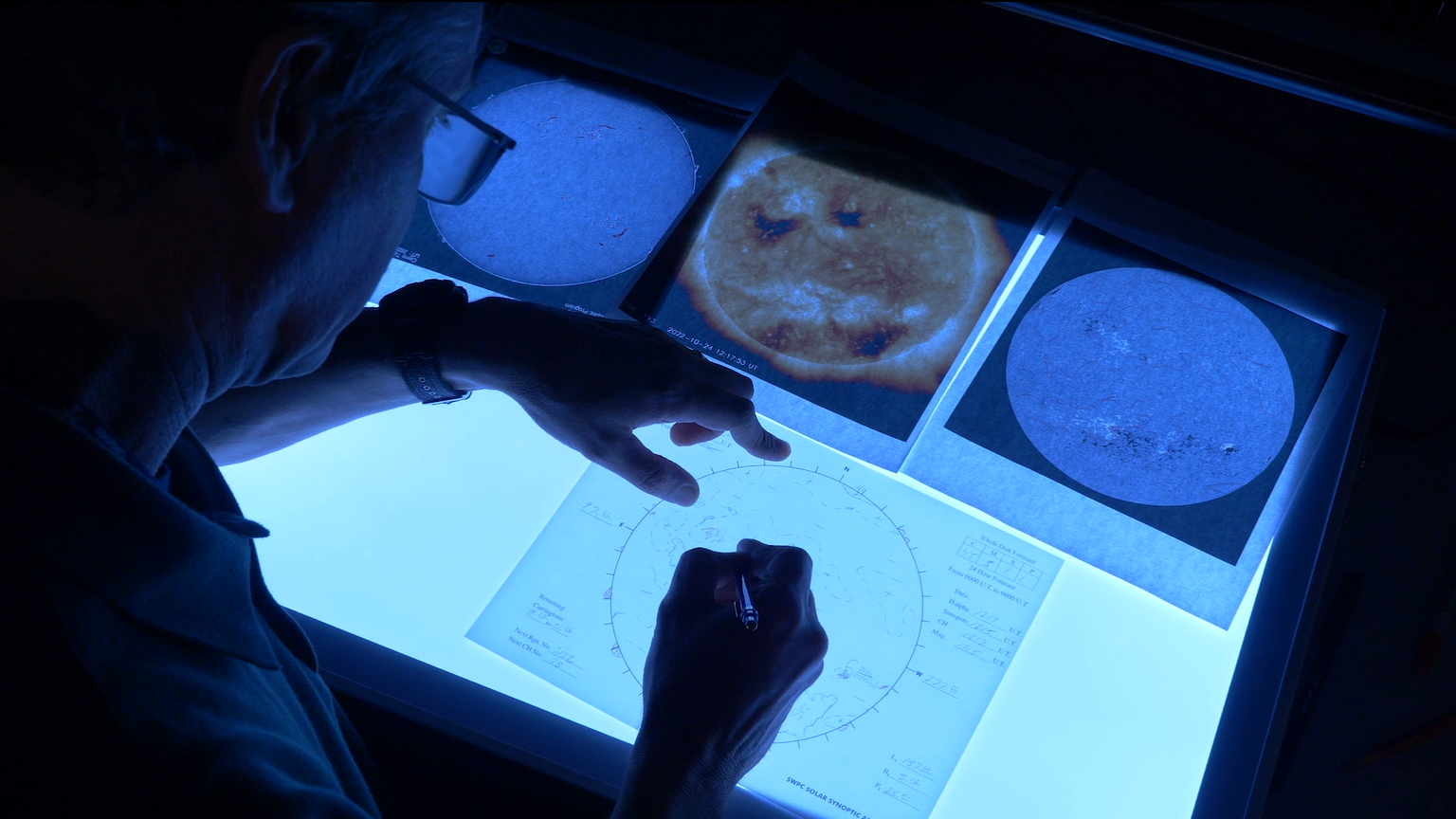

I can't help but start with: In the beginning, there was nothing. But it wasn't quite nothing. All stars form from the collapse of nebulae, which are loose clouds of gas and dust, and our sun — and solar system — are no different. Astronomers call it the "pre-solar nebula" and of course it isn't around today, but we've seen enough solar systems forming throughout the galaxy to get the general picture.

But a nebula on its own won't collapse into a solar system without something to set it in motion. In our case, we can thank a nearby supernova explosion, whose shockwave ripped through the pre-solar nebula, causing it to begin its contraction. We can tell that such a supernova went off nearby, because supernovae release great quantities of certain radioactive elements — elements that aren't normally found inside nebulae – but which we can see in our solar system today.

Once underway, the transition from nebula to solar system was irreversible. Over the course of millions of years, the nebula contracted and cooled, eventually reaching the point where a proto-sun was surrounded by a thin, rapidly rotating disk of gas and dust.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And then the fun began.

The planets emerge

Four and a half billion years ago, our sun wasn't quite the shining star that it is today. It was compact and very, very hot, but it hadn't reached the critical densities and temperatures needed to sustain nuclear fusion in its core.

But while it was still in this embryonic stage, the planets began their slow waltzing formation.

Close to the young sun, the heat and light were too intense for anything other than rocky material to remain; the ices evaporated and the loose gas like hydrogen and helium simply blew away. Those remaining rocky bits slowly coalesced, sticking together to form ever-larger clumps.

Eventually, with enough time (and the universe always, always has plenty of time to spare), those bits formed planetesimals, small almost-planets. There were a lot of them, and it was quite a violent time for our solar system as these planetesimals collided, shattered and reformed countless times. Our own Earth was struck by something nearly the size of Mars, and the debris from that impact eventually became our moon.

Out past what would eventually become the asteroid belt, however, planet formation took a different approach. Out there, it was cold enough for ices to survive, allowing planetary cores to grow to immense proportions in a short amount of time. Those large cores were then able to hoover up any surrounding material, like hydrogen and helium gas, enveloping those worlds in thick, swaddling atmospheres. That's how the giant planets were born.

Photos: Jupiter, the solar system's largest planet

The Late Heavy Bombardment

Once the planets matured, however, all was not calm in the solar system. The inner rocky worlds had stabilized, and the sun had ignited nuclear fusion. But the outer giant planets were surrounded by swarms of hangers-on — the leftover bits of debris from the chaotic planet-building process.

So they began to dance.

Astronomers suspect that the four giant planets of our solar system — Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune — initially formed much closer together than they are today, and subtle interactions with the remaining debris surrounding them caused them to shift their orbits. It took hundreds of millions of years to resculpt our solar system, and we're not exactly sure how it all went down.

In one scenario, Jupiter and Saturn migrate inward toward the sun, which caused Uranus and Neptune to drift outward. In another scenario, the worlds of our outer solar system play a game of gravitational hot potato with a bonus fifth giant planet that eventually got ejected altogether. In yet another, Jupiter wanders nearly to the orbit of Mars before jumping back out, disrupting the otherwise placid orbits of the remaining outer worlds.

No matter what, this last reshuffling caused havoc. Astronomers think that the migrating outer planets gave rise to an epoch called the Late Heavy Bombardment, a period of intense comet and asteroid impacts in the inner solar system about 4 billion years ago. The shifting of the giant worlds disturbed all the remaining material in the solar system, either sending them to safety in the frozen outskirts or barreling inward to cause trouble for the rocky planets.

Despite the violence, it wasn't all bad: the procession of comets raining in toward the inner solar system delivered an abundance of water to the rocky worlds, potentially making life, including us, ultimately possible — once the solar system settled down, of course.

Learn more by listening to the episode "AaS! 140: Who lives in the solar system?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to Mitchell L. for the questions that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.