How do astronauts use the bathroom in space?

To boldly go! Astronauts may seem superhuman, but they have the same basic needs as the rest of us, and that includes using the toilet in space.

"Do it in the suit."

Those were the disconcerting words that the first American in space, Alan Shepherd, heard on May 5, 1961, when he advised the launch pad team he needed to urinate. Shepherd did as instructed, urinating in his spacesuit, short-circuiting his electronic biosensors.

Shepherd's spacesuit hadn't been outfitted with a urine collection system because his mission had not been expected to last long enough for him to need to urinate.

NASA didn't take any such chances with John Glenn's mission to space during the first Mercury orbital flight on February 20, 1962. Glenn's spacesuit was equipped with the first functioning urine collection system, a wearable containment belt, latex roll-on cuff, plastic tube, valve and clamp, and a plastic collection bag, which would inform systems used by male astronauts throughout the space shuttle program. In fact, Glenn's urine collection system is so historic it has been on display to the public at the National Air and Space Museum since 1976.

Related: This is the astronaut's video guide to going to the bathroom in space

Since the Mercury orbital flights and the space shuttle program, stays in space have become longer, with astronauts at the International Space Station (ISS) staying for up to six months. And the new era of extended space stays is upon us, meaning astronauts who must wear clothes for long periods can't be walking around in damp or soiled underwear or attached to rubber hoses. This has led to a drive to design and build space toilets to perform the most basic of human needs in space while considering utility and comfort.

How do toilets work in space?

Toilets come in an array of forms here on Earth, depending on culture and geographical location. But one single principle applies to all toilets on terra firma, whether a hole in the ground or a golden throne with a built-in bidet, waste disposal hinges on gravity, Associate Professor of Geology, University at Buffalo Tracy Gregg wrote in the Conversation.

The microgravity experienced in space can make the process of disposing of human waste more tricky and even dangerous. The lack of gravity means waste could float from space-based toilers, which would not only be harmful to astronauts' health, but if this occurred aboard the ISS or another space station, free-floating waste could damage sensitive equipment.

This means rather than relying on gravity to dispose of waste, toilets on the ISS and on spacecraft use suction and airflow. According to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), the weak gravity of space means, as well as using suction, that astronauts on the space shuttle have to strap themselves to the toilet as they go about their business.

The microgravity is counteracted by a wealth of handholds and footholds that ensure an astronaut won't drift off the toilet at a critical moment. While urinating, astronauts hold a suction funnel to their skin to prevent leaks. When the toilet lid is lifted to pass solids, suctioning begins immediately to reduce odors, according to Gregg.

What happens to the waste?

Solid waste passed into toilets in space is sucked into garbage bags that are then placed in airtight containers. Toilet paper, wipes, and gloves are also placed in these containers. These containers are loaded into the cargo ships that bring resources from Earth to the crew of the ISS. These ships are then dropped back into the atmosphere of Earth, where they burn up permanently, disposing of astronauts' solid waste. Some feces is freeze-dried and returned to Earth for testing.

Disposal of astronauts' liquid waste on the ISS is more complicated. Water is such a valuable resource in space that urine can't just be allowed to be destroyed in the atmosphere. Each crewmember of the ISS needs about 1 gallon (3.8 liters) of water each day for drinking, food preparation, and hygiene uses like brushing teeth. Urine is collected by toilets on the ISS and is passed to the Water Recovery System, which also collects sweat and moisture in expelled breath. This is then forwarded to the Water Processor Assembly (WPA), which then turns it into drinkable water.

"We recycle about 90% of all water-based liquids on the space station, including urine and sweat," NASA astronaut Jessica Meir said. "What we try to do aboard the space station is mimic elements of Earth's natural water cycle to reclaim water from the air. And when it comes to our urine on ISS, today's coffee is tomorrow's coffee!"

Currently, feces isn't recycled to extract wastewater, but this is something that NASA is working on.

Advancements in space toilets

The first space toilet was designed for use in NASA's Skylab orbiting platform, the first space station, in 1973. The toilet was little more than a hole in the wall attached to a bag and fan that astronauts defecated in during 1973 and 1974 missions, heat-drying feces.

The ISS toilets were first designed in 2000, with all astronauts having to urinate while standing up and defecate while strapped to the toilet and their rears vacuum sealed to the seat. Gregg explained this didn't didn't work very well and was hard to keep clean.

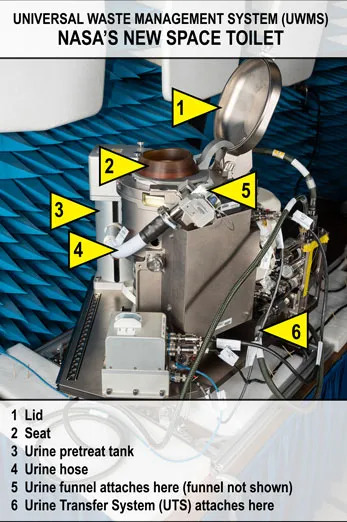

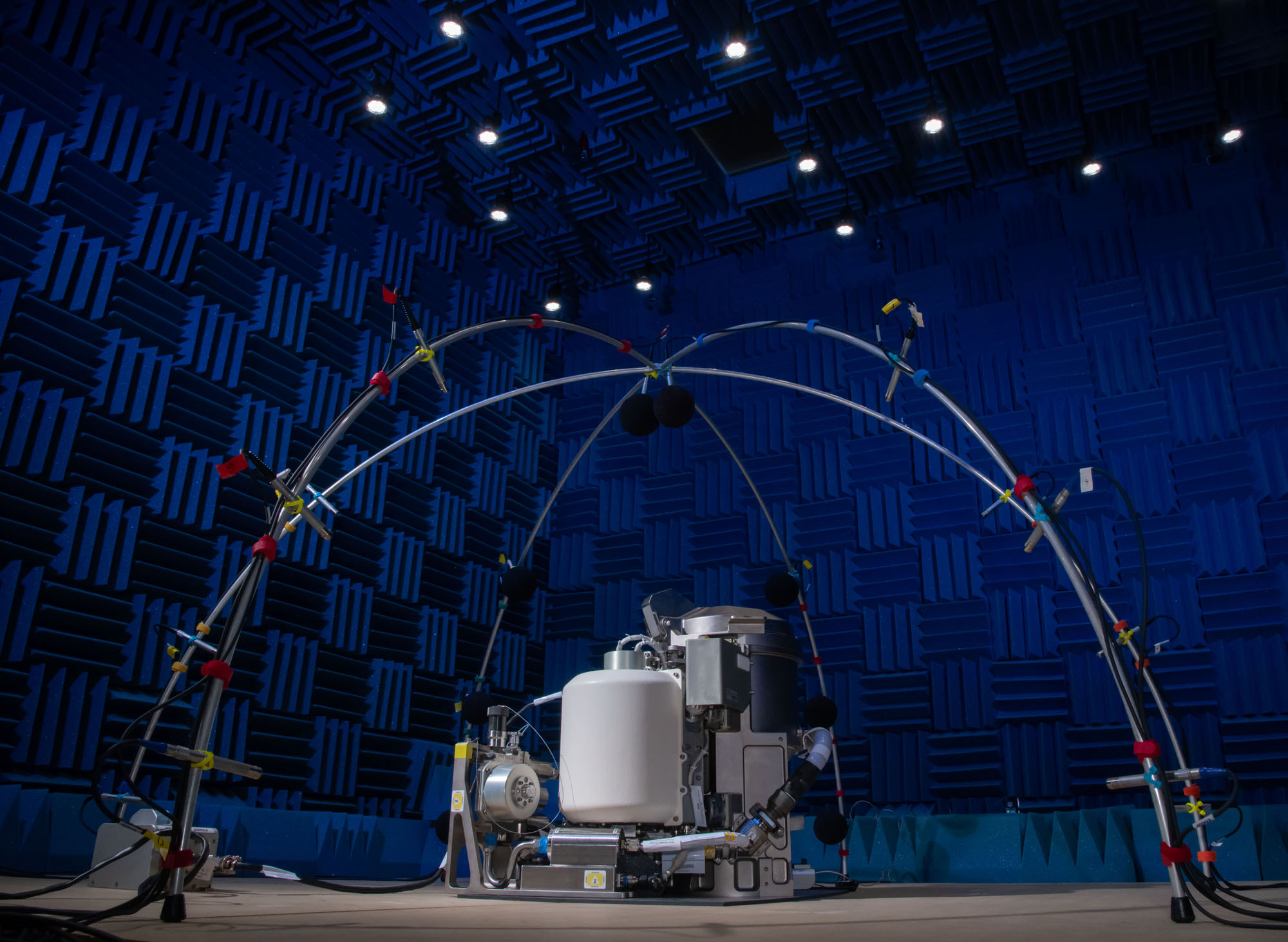

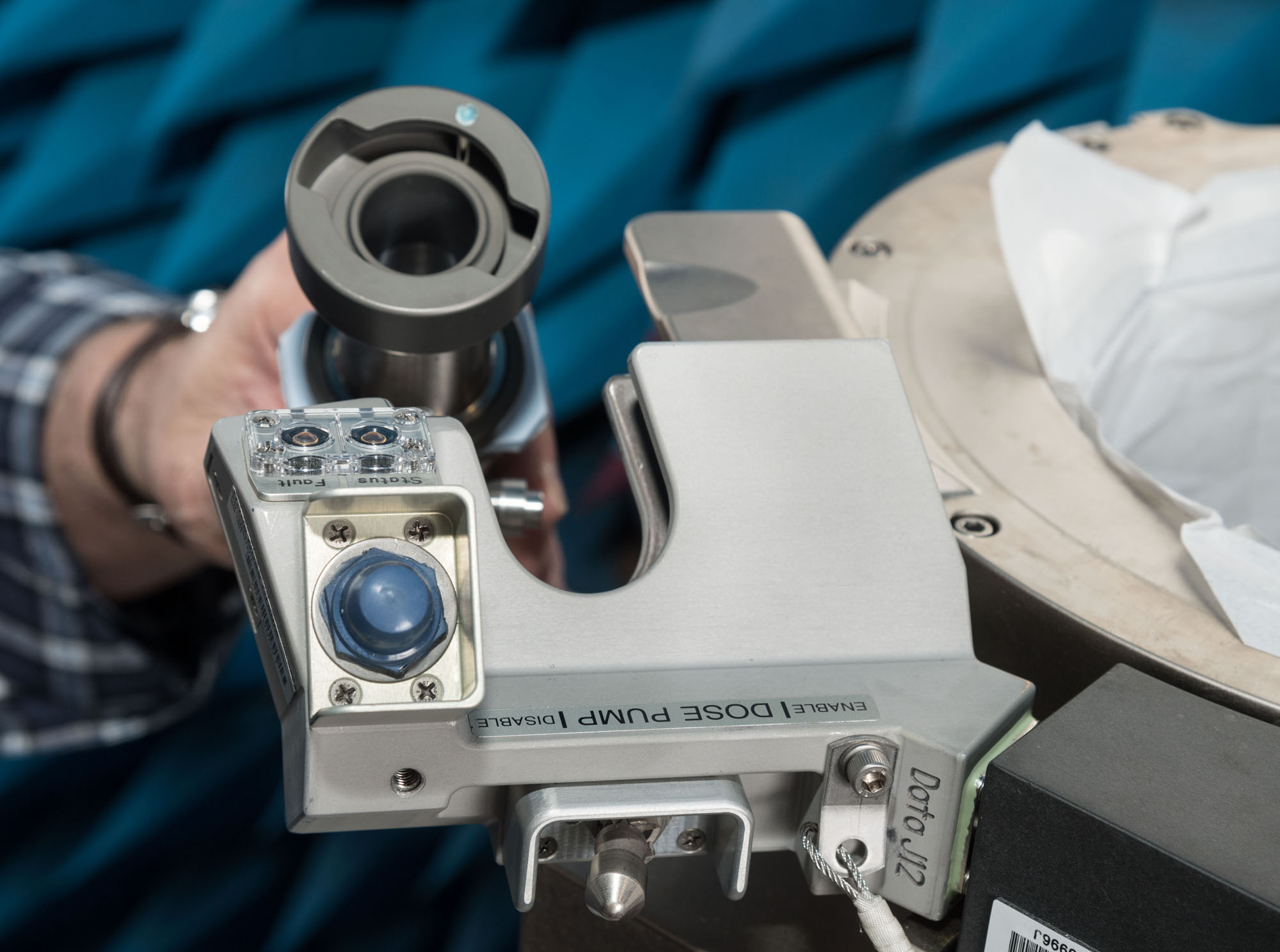

Thus, in 2018, NASA developed its first new space toilet for decades, taking astronaut feedback about existing facilities into account. The result was a titanium unit called Universal Waste Management System (UWMS) that cost $23 million to develop. The toilet, which was sent to the ISS in 2020, is 28 inches (71 centimeters) tall, making it around half the size of the Russian-constructed toilets at the space station. On the ISS, toilets are located in the Zvezda, Nauka, and Tranquility units.

The comparatively small size of the UWMS space toilet is a result of the fact that is designed to be fitted into the Orion space capsule, the crew vehicle of the Artemis mission. As part of the Artemis III mission, the Orion capsule will carry the first woman to the moon.

Fittingly, while previous space toilets were outfitted specifically for men, making them uncomfortable and inconvenient for women to use, the UWMS toilet has been designed to be better suited to women. Johnson Space Center's Melissa McKinley headed up the project and explained that the toilet seat had been tilted and raised to make it easier to use while seated. The newer toilet has also been designed with elongated and scooped-out funnels that allow astronauts to urinate and defecate at the same time. McKinley added that prior to this, astronauts had been forced to choose one function at a time.

Space hygiene FAQs

How did Apollo 11 astronauts go to the bathroom?

The Apollo 11 astronauts didn't have toilets. Instead, they urinated into a urine collection device worn under their clothing, which they attached to themselves using roll-on cuffs. The urine was transferred through a rubber transfer tube to a tank, from where the majority of the liquid waste was vented into space with a small amount was freeze-dried and stored for testing upon return to Earth.

How do astronauts wash clothes?

The simple answer to this is 'they don't.' Because water is such a limited resource on the ISS astronauts on the space station wear their clothes until they are too dirty to continue to wear, according to the Canadian Space Agency. After this, they place the clothes into waste receptacles, and they are eventually burned up in the atmosphere. Washing clothes in space is also unfeasible because any detergent used would make the recycling process and water purification difficult.

Where do astronauts get water from when in space?

Water is recycled constantly on the ISS, with NASA aiming to achieve the recycling of 98% of used water expelled by the crew in sweat, breath, and urine. This is handled by the ISS's Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS), including its Urine Processor Assembly (UPA), Water Recovery System, and Water Processor Assembly (WPA).

Additional resources

European Space Agency astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti takes viewers on a tour of the ISS explaining the complicated and slightly intimidating toilet system. In this video, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency astronaut Koichi Wakata explains the water recovery system of the ISS, which recycles urine and wastewater into clean water. The infographics Show explains how NASA's $23 million toilet works.

Bibliography

How do astronauts go to the bathroom in space? The Conversation, [2021], [https://theconversation.com/how-do-astronauts-go-to-the-bathroom-in-space-153370]

Life Support Subsystems, NASA Johnson Space Center, [accessed 02/09/24], [https://www.nasa.gov/reference/jsc-life-support-subsystems/]

Boldly Go! NASA's New Space Toilet Offers More Comfort, Improved Efficiency for Deep Space Missions, NASA, [accessed 02/09/24], [https://www.nasa.gov/humans-in-space/boldly-go-nasas-new-space-toilet-offers-more-comfort-improved-efficiency-for-deep-space-missions.]

How do toilets work in space? JAXA, [accessed 02/09/24], [https://iss.jaxa.jp/kids/en/life/04.html]

H. Hollins, Forgotten hardware: how to urinate in a spacesuit, Advances in Physiology Education, [2013], [https://journals.physiology.org/doi/full/10.1152/advan.00175.2012]

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

Unclear Engineer I can still remember when Congressmen were giving NASA a hard time for "spending $1,000,000 on a toilet seat" during budget hearings. Too bad it wasn't feasible to send them up for a week. That would have been a great mind-changer!Reply