How NASA's OSIRIS-APEX asteroid probe survived its 1st close encounter with the sun

'It's phenomenal how well our spacecraft configuration protected OSIRIS-APEX.'

OSIRIS-APEX emerged "unscathed" from its closest-ever brush past our sun on Jan. 2, scientists announced on Tuesday (May 28).

The probe, originally known as OSIRIS-REx, aced its sample-return mission to the asteroid Bennu and is now headed to the space rock Apophis on an extended mission. That new mission calls for OSIRIS-APEX to glide 25 million miles (40 million kilometers) closer to the sun than it was designed to operate. Scientists deem several such close passes necessary for the probe to get on a path to reach Apophis in 2029.

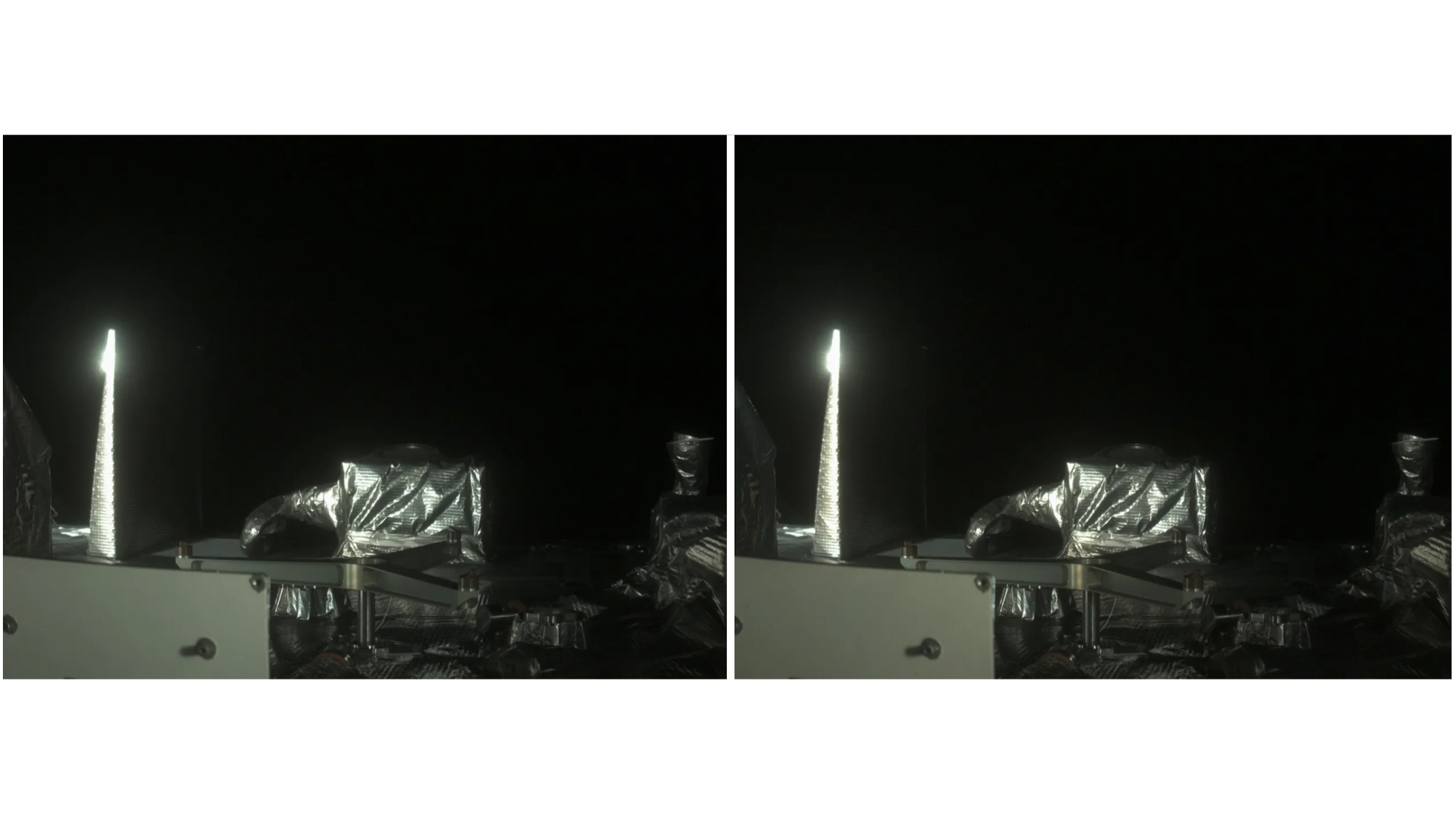

OSIRIS-APEX is in an elliptical orbit around our sun, which puts it at a point closest to the star once every nine months. Its first such close approach occurred on Jan. 2. To prepare for the intense blast of radiation, in early December the mission team tucked in one of OSIRIS-APEX's two solar panels such that it shaded the probe's most sensitive instruments, while the second panel faced the sun in order to power the spacecraft.

Related: How NASA's OSIRIS-REx mission will help protect Earth against asteroid Bennu and its flyby in 2182

This bit of creative engineering protected the spacecraft during its dangerously close approach to the sun, just like computer simulations had previously predicted, the mission team shared this week in a NASA statement.

"It's phenomenal how well our spacecraft configuration protected OSIRIS-APEX, so I'm really encouraged by this first close perihelion pass," said Ron Mink, the mission systems engineer for OSIRIS-APEX at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland.

Telemetry data downloaded from the spacecraft in mid-March assured scientists of its good health. By early April, the probe had gotten far enough away from the sun to resume normal operations, according to the NASA statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists and engineers were also pleasantly surprised to note that an onboard camera fared even better than expected after being exposed to high temperatures during the encounter. MapCam, a medium-range camera that previously mapped Bennu in color and will also map Apophis, saw a 70% reduction in cumbersome white spots called hot pixels since April of last year, the last time the camera was tested.

Hot pixels occur due to prolonged exposure to solar radiation and are a common issue for cameras in space. While they are normally resolved with controlled heat using onboard heaters, OSIRIS-APEX's camera was restored naturally, thanks to the spike in heat from the close solar encounter, scientists said.

While mission team members are relieved that OSIRIS-APEX is safe after its first close approach to the sun, they noted that it's unclear how five more such encounters may impact the probe and its instruments.

The next closest approach to the sun is scheduled for Sept. 1, when the spacecraft will once again pass within 46.5 million miles (74.8 million km) of the sun's surface, well within the orbit of Venus and well beyond the probe's originally envisioned operational limits.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social