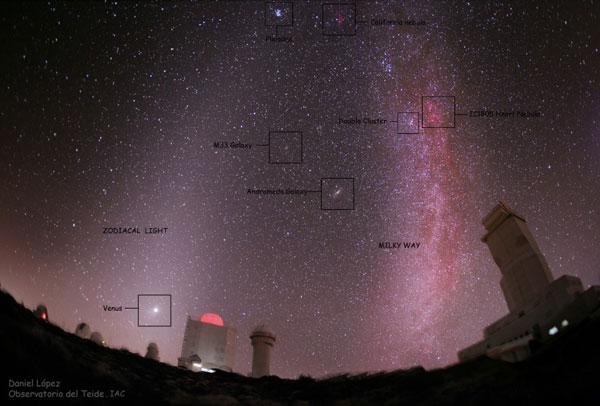

Zodiacal light: How to spot the rare celestial glow in the night sky

One of the sad things about the significant increase in light pollution over these past 30 or 40 years is that it is making certain celestial sights all that more difficult to see. One of these is a phenomenon that I myself have only seen firsthand twice in more than a half-century of skywatching. For someone who has spent the majority of his life in brightly-lit environments, sighting it was a real treat for me. The first time came in April 1986, when I led a tour group to the supremely dark skies of the Andes Mountains in Chile to view Halley's Comet.

The second time came in 2001, when I spent several nights in the desert country of southern Arizona, a trip timed specifically to coincide with a predicted storm of Leonid meteors. It was on the first night of that trip, under a magnificent star-spangled sky, that I again saw what I had seen 15 years earlier in Chile.

It actually crept up on me with no advance notice.

Related: Zodiacal light: how to see the mysterious glow

Where did that town come from?

It was around 3 a.m. when rather near to the eastern horizon I noticed some sort of a very faint, whitish, diffuse glow. After about a half-hour later, when I again looked in the same direction, I could still see the glow, although it now appeared somewhat brighter and appeared to be reaching a bit higher into the sky. After another half-hour, the glow seemed brighter still and now extended well up into the eastern sky. I was really puzzled. It was almost as if some town or a distant city had suddenly materialized from beyond the nearby hills and was producing some sort of light haze protruding upwards against the sky. I then checked my watch ... no, dawn was not due to break for at least another hour or so.

Then, all at once, I realized what I was looking at. "Of course!" I said to myself. "I'm looking at the zodiacal light!"

There was no need for me to feel embarrassed, for over the ages countless others have been fooled as well. In fact, the Persian astronomer, mathematician and poet Omar Khayyam (1048 -1141) made reference to it as a "false dawn" in his one long poem, "The Rubaiyat."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Reflected light from meteoroids

That faint ghostly glow was once thought to be solely an atmospheric phenomenon: possibly reflected sunlight shining off the very high atmosphere of Earth. Today we know that while it is indeed reflected sunlight, it is being reflected not off our atmosphere, but rather off of a non-uniform distribution of interplanetary material; debris likely left over from the formation of our solar system.

These countless millions (or perhaps billions) of particles — ranging in size from small boulders to micron-sized dust grains — seem densest around the immediate vicinity of the sun, but extend outward, beyond the orbit of Mars, and are spread out along the plane of an imaginary line on the sky called the ecliptic (a path that the sun follows throughout the year). Hence the reason for the name "zodiacal" light; is because it is always seen projected against the zodiac constellations.

Though meteoric particles are concentrated in this region, they are widely separated. If, for example, the particles were of pinhead size and five miles apart, there would still be enough within the Earth's orbit to reflect the amount of light that is usually observed.

When and where to look

The best time to see the zodiacal light is when the ecliptic appears most nearly perpendicular to the horizon. For those in the Northern Hemisphere, the best time to see it is after sunset during February and March, in the western evening sky. The best morning views — in the eastern sky — come during August and September (though I made my Arizona sighting in mid-November).

Conversely, for those who live in the Southern Hemisphere, the best view in the western evening sky comes after sunset in August and September, while the best morning view in the eastern sky comes from late March into the early part of May.

It presents a somewhat ill-defined shape, almost like a tilted cone, wedge or slanted pyramid. At the base of the cone, the light may extend some 20 to 30 degrees along the horizon (your clenched fist held at arm's length measures roughly 10 degrees). When seen at its best, it might appear as conspicuous as the Milky Way in brightness, but more often than not, contrasting only slightly with the background sky, it is so faint that even a thin haze or high cloud can obscure it.

Those who live in the tropics or at the equator are most fortunate, since the zodiacal light is always conspicuous from these regions. This is probably because from these locations the ecliptic is always favorably oriented vertically, allowing views both in the western evening sky and eastern morning sky through the entire year.

For northerners at this particular time of the year, it is just after evening twilight ends (about 90 minutes after sunset), that the zodiacal light should appear at its brightest and most conspicuous.

It would also help to use what astronomers call "averted vision." This is a technique used to see faint objects visually. It involves looking to one side of an object's position, rather than directly at it, so that light falls on to the outer part of the retina, which is more sensitive than the center of vision. For viewing the zodiacal light, this technique will put it on the most sensitive part of your eye, and improve your chance of seeing it.

Restrictions apply

As I noted at the beginning of this essay, getting a view of this ethereal glow has gotten more difficult thanks to the increase in light pollution. Only those who live far from population centers can still enjoy an old time pollution-free view of the heavens. The rest of us are handicapped, as I am at my home in Putnam County some 50 miles (80 kilometers) north of New York City. The big metropolis illuminates the southern sky up to an altitude of about 40 degrees, but it's light from local sources, such as shopping centers in nearby northern Westchester, that has caused my night sky to deteriorate toward an unacceptable level.

When the stars in a planetarium are suddenly turned on, lecturers are in the habit of ascribing to the beauty of the sight the "oohs" and "ahs" of big-city audiences. But perhaps some exclamations are expressions of disbelief by people who have never seen what the real sky looks like! Celestial sights like the Milky Way and Zodiacal Light can be appreciated only when the sky is truly dark.

Another challenging sight

On exceptionally clear nights, the zodiacal light might be seen to reach more than halfway to the point directly overhead. In fact, should you be blessed with such conditions — absolutely no artificial lighting, smoke or haze — you might also try to see the zodiacal band, which runs along the entire ecliptic and usually averages about 5 to 10 degrees in apparent width.

Also difficult to see, though perhaps a trifle brighter than the zodiacal band is the "counterglow" or gegenschein. This is a very faint oval patch of light about 10 to 20 degrees long and 6 to 8 degrees wide (overall, comparable in size to the Great Square of Pegasus) and situated exactly on the ecliptic at that point diametrically opposite to the sun in the sky. It too is interplanetary material that lies out in space beyond the orbit of Earth. It may appear ever-so-slightly brighter than the zodiacal band due to the fact that the meteoric particles directly opposite to the sun reflect more sunlight toward us than is reflected by particles in portions of the band that are not directly opposite the sun.

To see the gegenschein with certainty is no small accomplishment. It requires not only absolutely black skies, but unusual perception and visual acuity. Moreover, if it occurs anywhere in or near the Milky Way, it will be hopelessly lost in its light. The gegenschein should be centered about 10 degrees to the lower left of the second-magnitude star, Denebola in a rather star-poor region of the sky. Because of its extreme faintness, your best chance of glimpsing it is to use averted vision. Try this: look directly toward that spot in the sky where the gegenschein should be, then turn your eyes slowly to one side. Slowly returning your eyes to the spot, you just might be able to discern this large — albeit exceedingly faint — hazy patch.

Good luck!

- Source of night sky's cosmic zodiacal glow explained

- Zodiacal light Meets 'gegenschein' above ESO's Very Large Telescope (photo)

- Ghostly zodiacal light glows over Death Valley (photo)

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.