This Hubble Telescope galaxy image could help reveal how stars are born (photo)

NGC 4654 is a spiral galaxy with some interesting nuances of stellar formation.

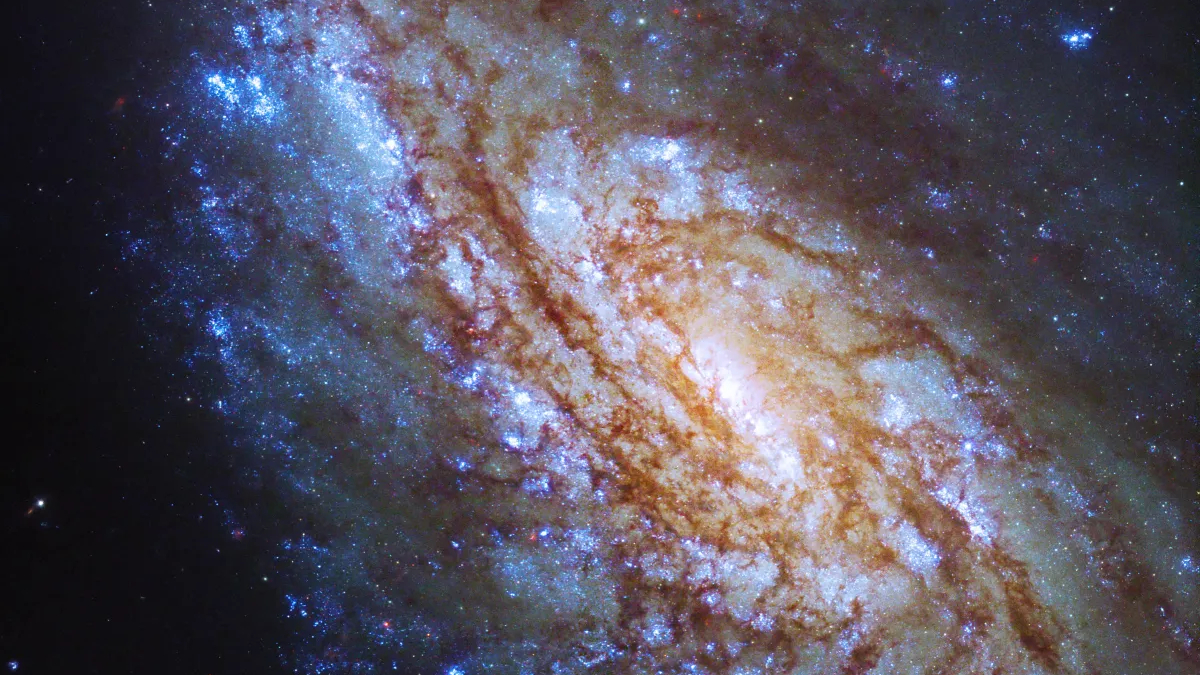

With its fluorescent blues and espresso-brown hues, this Hubble Space Telescope image of the Virgo Cluster galaxy is undeniably worth a double-take. It's part of NASA's endeavor to share a new galactic image every day from Oct. 2 and Oct. 7, a lovely treat for space-gazers everywhere.

But, like with all beautiful space visuals, the book behind the stars is often just as striking as the cover.

What you're looking at here are the swirling spiral arms of a galaxy named NGC 4654, which is located some 55 million light-years from Earth. Right off the bat, that means we're seeing this realm as it was 55 million years ago, because one light-year equals the time it takes for light to travel one year. Once this galaxy's photons finally reached the Hubble Space Telescope, the observatory was able to capture their source in visible, ultraviolet and even infrared wavelengths. And this image is the product of its effort.

Related: Hubble Space Telescope sees spiral of star formation in neighboring galaxy

Over 500 million years ago, according to a statement accompanying the image, NGC 4654 is believed to have interacted with another galaxy known as NGC 4639, and the latter is thought to have stripped the former of some gas along its edge. Presumably, that happened as a result of NGC 4639's gravitational pull. Ultimately, scientists think this interaction limited star formation at NGC 4654's edge because all that interstellar gas contains the parts required to make new generations of stars in the first place.

In fact, that's why NASA says studying galaxies like this stunning one we see in the Hubble photo is important. It's a way to investigate how stars form. And understanding how stars form is crucial for a variety of reasons — for example, it could help us study how planets are born around stars the way Earth came together around the sun.

NGC 4654 is one of many galaxies in the Virgo constellation, a celestial dot-to-dot that's actually the second-largest constellation in the sky. Visible to anyone in the northern hemisphere and to most in the southern hemisphere (though not exactly very easily), NGC 4654 is considered an "intermediate" galaxy because it contains two types of hypnotic arms — barred and unbarred.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Barred spirals have ribbons of stars, gas and dust that cut across their central regions like, yes, "bars." Unbarred spirals do not.

Further, the release states, NGC 4654 has an asymmetric distribution of stars and neutral hydrogen gas — possibly due to a process where the entire Virgo cluster puts pressure on the galaxy as it moves through what's known as the intracluster medium. That's basically a superheated plasma, or ocean of charged particles, made mostly of hydrogen.

"This pressure feels like a gust of wind – think of a biker feeling wind even on a still day — that strips NGC 4654 of its gas," the release says. Peculiarly, that process also is expected to have halted star formation in the galaxy, yet NGC 4654 appears to have popped up stellar bodies at a similar rate to its unaffected galactic siblings. Voila: There's another reason to figure out the connection between cold gas in galaxies and star formation.

A friendly reminder that even though other telescopes have earned the spotlight recently, most notably the James Webb Space Telescope, Hubble is still wonderfully trudging along.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.