Behold! Hubble telescope catches stunning photos of planetary nebula fireworks

Incredible new images from the Hubble Space Telescope reveal nearly dead stars spewing blasts of hot gas into deep space in strange but stunning ways.

From studying those images, scientists now suspect that two spectacular nebulas are each powered by a pair of stars merging together. As they do so, the stars spit shock waves of energy through the surrounding gas and dust the stars have previously leaked. Scientists used the full range of Hubble's instruments

"When I looked in the Hubble archive and realized no one had observed these nebulas with Hubble's Wide Field Camera 3 across its full wavelength range, I was floored," Joel Kastner, an astronomical imaging specialist at Rochester Institute of Technology in New York and lead author of the new study, said in a statement.

Related: 50 fabulous deep-space nebula photos

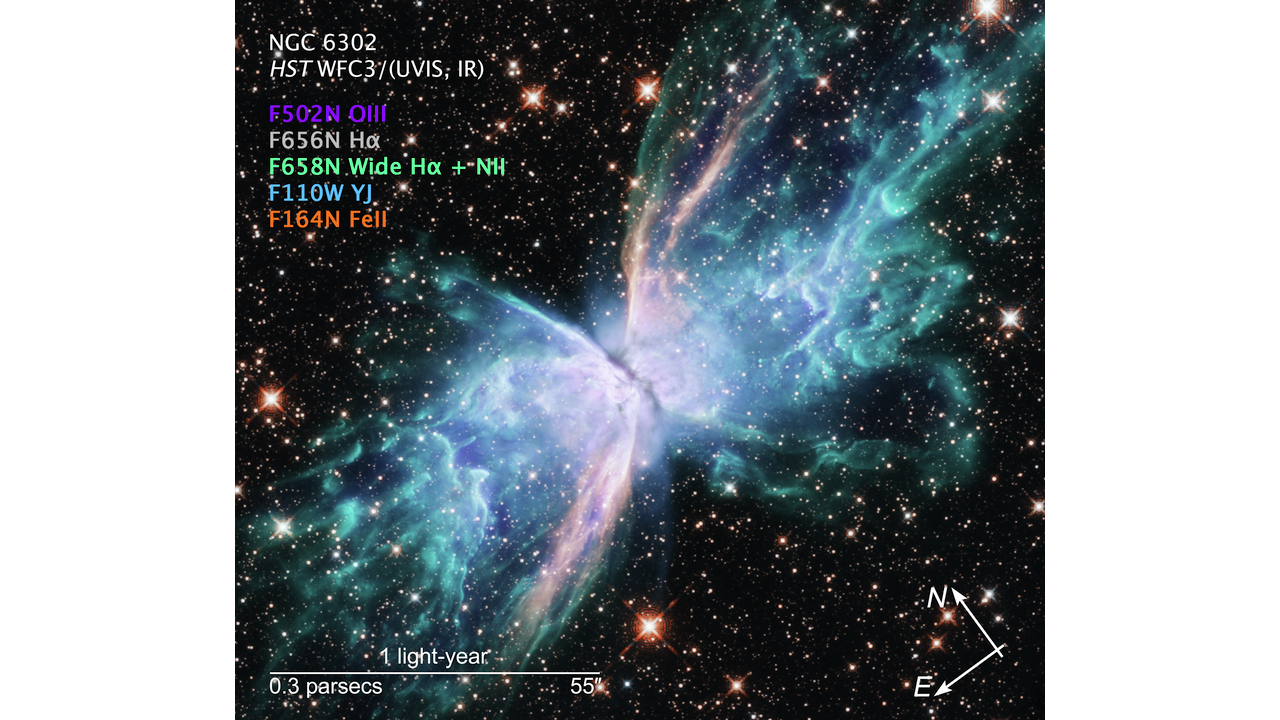

Hubble has studied plenty of nebulas over its 30-year career, of course. But most of those images have relied primarily on optical and near-infrared light only, according to the scientists behind the new research. The new images add near-ultraviolet light as well, incorporating the whole range of light wavelengths that Hubble can observe.

"As I was downloading the resulting images, I felt like a kid in a candy store," Kastner said. "These new multi-wavelength Hubble observations provide the most comprehensive view to date of both of these spectacular nebulas."

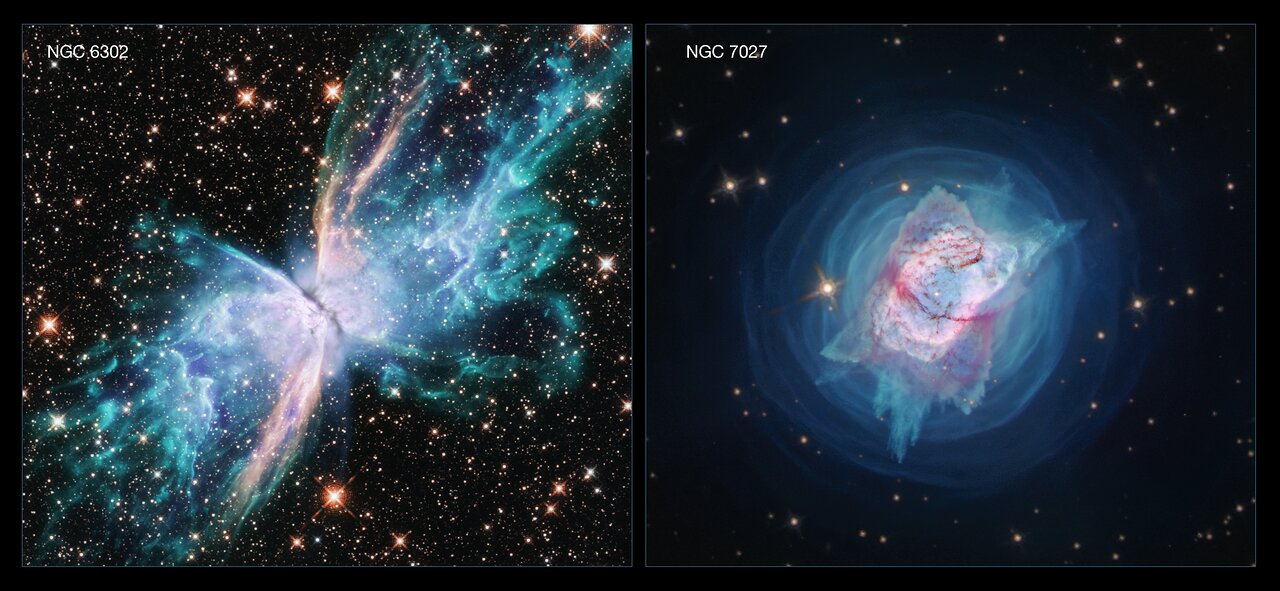

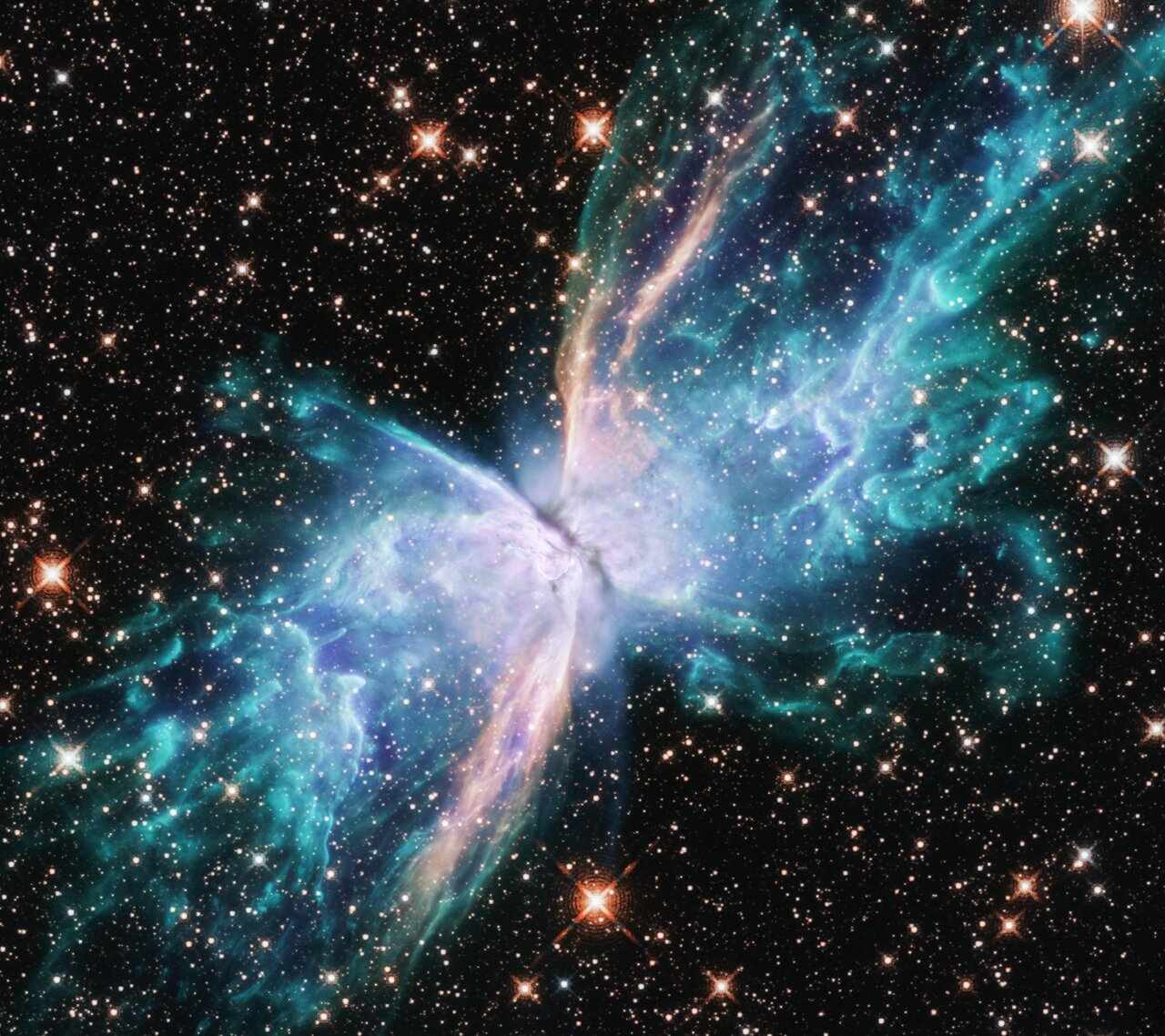

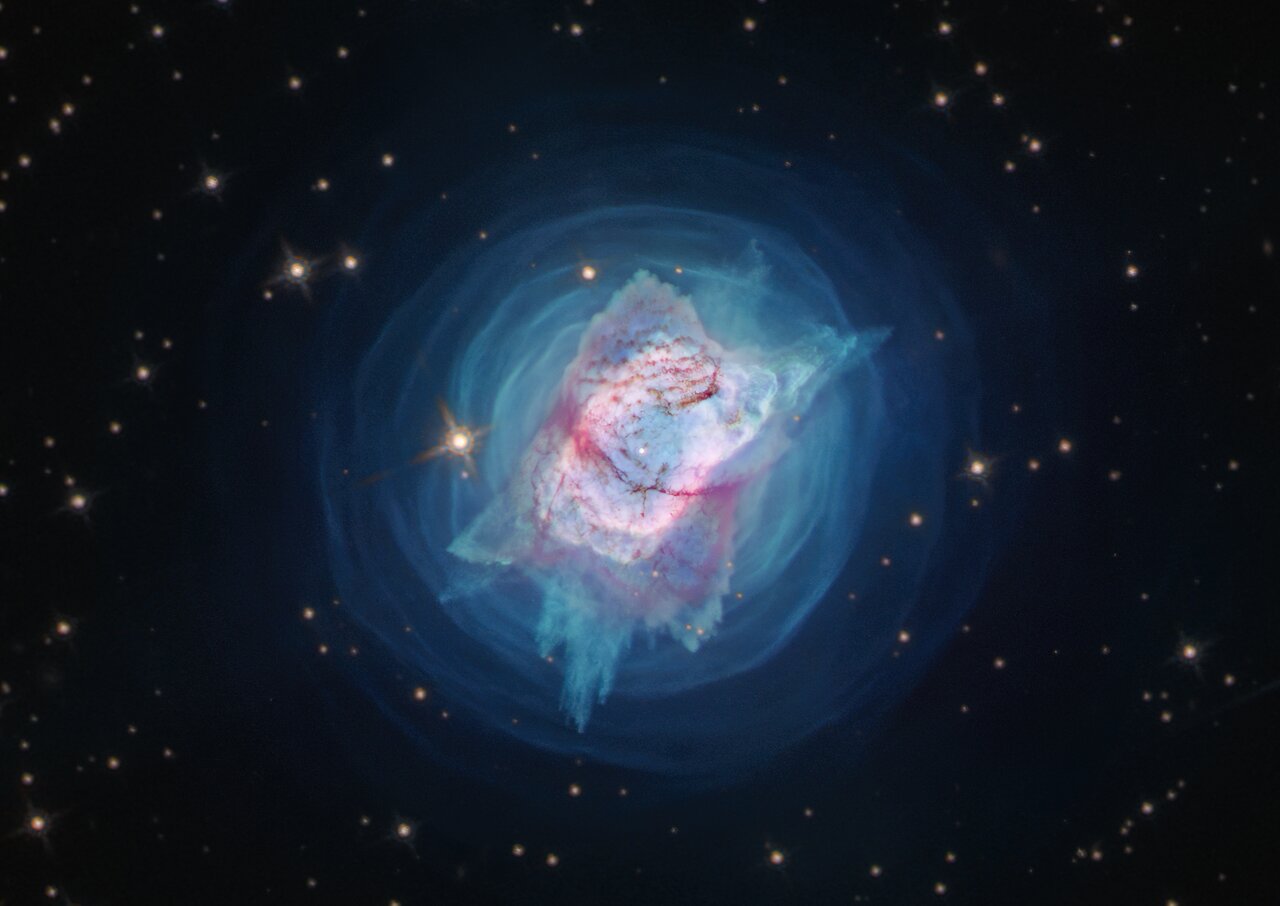

Those nebulas are known formally as NGC 6303 and NGC 7027. The first is nicknamed the Butterfly Nebula because it appears to sprout two large, delicate wings; the latter reminds the researchers on the current project of a jewel bug with a hard, metallic case. Both nebulas are relatively young, and the Butterfly Nebula is particularly well studied.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But despite plentiful past studies of the nebula, scientists see new details in the new Hubble observations, in particular the pinkish S-shaped line running from the upper right to lower left of the image. That line marks a specific type of iron called singly ionized iron, unusual in structures like this one.

"This iron emission is a sensitive tracer of energetic collisions between slower winds and fast winds from the stars," Bruce Balick, an astronomer at the University of Washington and a co-author on the new research, said in the same statement. "It's commonly observed in supernova remnants and active galactic nuclei, and outflowing jets from newborn stars, but is very rarely seen in planetary nebulas."

In addition, the scientists say that the twisted, asymmetrical nature of the iron emissions suggests that the Butterfly Nebula, which is 2,500 to 3,800 light-years away from Earth, is home to two unevenly matched stars.

Meanwhile, the jewel bug-like nebula shows a different type of violent activity. "Something recently went haywire at the very center, producing a new cloverleaf pattern, with bullets of material shooting out in specific directions," Kastner said.

He and his colleagues believe that here, 3,000 light-years away from Earth, a massive red giant star has recently swallowed its companion star. If this hypothesis is correct, the shell-like bubbles are made of gas that was slowly ejected over the long death spiral of the stars, while the more angular interior emissions date to the pair's collision.

In both cases, mergers at the heart of the nebulas seems to be responsible for their dramatic appearances, according to the scientists.

"The hypothesis of merging stars seems the best and simplest explanation for the features seen in the most active and symmetric planetary nebulas," Balick said. "It's a powerful unifying concept, so far without rival."

The research is described in a paper published June 15 in the journal Galaxies.

- The best Hubble Space Telescope images of all time!

- The Hubble Space Telescope and 30 years that transformed our view of the universe

- Glowing nebula decorates space in Hubble image

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.