'Finding Our Place in the Universe' Details Quest for Earth's Supercluster: Author Q&A

Finding Laniakea was an adventure.

The newly translated book "Finding Our Place in the Universe," out today (May 21), details how scientists discovered the vast supercluster of galaxies that contains the Milky Way — using careful calculations to reveal the supercluster's intricate, feathery shape.

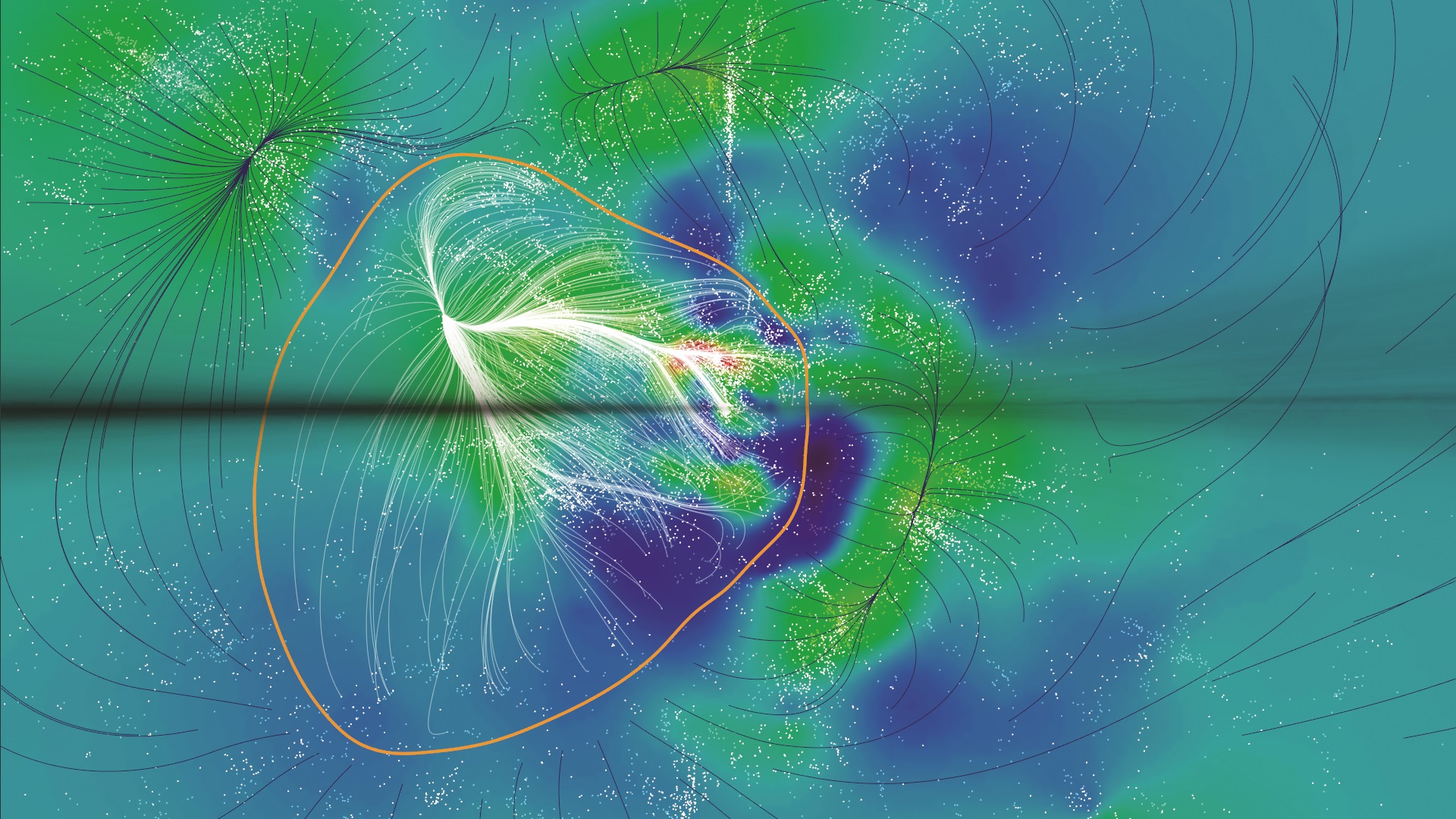

In 2014, the French astrophysicist Hélène Courtois was part of a research team that discovered the supercluster, which is known as Laniakea ("immeasurable heaven" in Hawaiian). Laniakea is more than 500 million light-years in diameter and contains approximately 100,000 galaxies, the brightest of which is our own Milky Way. Those galaxies appear to be moving toward what is known as the "Great Attractor," an unseen force 160,000 million light-years away that pulls galaxies within Laniakea toward it inexorably.

To determine Lanaikea's extent, the research team measured the distance from Earth to other galaxies and then measured each galaxy's movement due to other objects' gravitational pull. The scientists found that some galaxies tended to move in one direction, some in another — but since every galaxy is moving toward a spot called the Great Attractor, there is an outer bound even for something as large as Lanaikea. As of 2014, we have known where that outer bound lies. Now that Laniakea has been identified, Courtois is focusing on finding the causes of an ongoing, accelerated expansion of galaxies.

Related: Will the Great Attractor Destroy Us?

Courtois, a professor at the University of Claude Bernard Lyon 1 in France, wrote a French account of the discovery of Laniakea in 2016. Now, MIT Press has published an English version entitled "Finding Our Place in the Universe." The book details Courtois' own journey as an astrophysicist, while simultaneously telling the story of more than two decades of work that culminated in the discovery of Laniakea. It is an accessible and engaging volume, light on equations but teeming with personal anecdotes. Space.com caught up with Courtois recently to discuss the quest for Laniakea, what happens now and why science should never be solemn.

Space.com: Why did you choose to tell the story of discovering Laniakea as a quest?

Hélène Courtois: I like storytelling. When I was attending a lecture as a student, I really liked when the person would make it sound like a story. I thought it was better to give the story the way I experienced it in time, rather than to give a chapter on how you do you astrostatistics, how you do observation, how you do …

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It's a little bit less common, maybe, to do it this way. So I was eager to try it as a story.

Space.com: You mention toward the beginning of the book that in some cases you gave up mathematical precision or very precise science in order to be comprehensible. Why did you make that decision?

Courtois: It was easy for me to make this decision, because, actually, I like to talk to the large public about science. I understood very quickly that you don't need equations, actually, if you give people a sense of physics. To me, mathematics is a language, so I can explain things using mathematics, but I can also explain the same things using words. Mathematics is just another language which allows you to go into some more abstract concepts, but you don't need them in order to understand the big picture of a story.

I like to be able to explain this science to a 6-year-old kid, a teenager and someone who already knows a lot of things — and I can adapt.

Space.com: You highlight unheralded women in the history of astrophysics throughout the book. Do you think astrophysics has become more appreciative of women's contributions in your lifetime?

Courtois: In France, only 9% of full professors in particle physics or astrophysics are women, while at entrance of university, there are 25% of girls in physics. There should be at least 25% women full professors. My idea to highlight women astronomers was to show that it's possible. It was not really to make a big deal about it, because my male colleagues are supernice, supercool. I love them. We have no problems. But we don't see enough girls in STEM. And I don't really know why. ... It's not a problem between girls and boys. It's something else.

Space.com: Another theme of your book is that science is a process of continuous discovery and learning and being willing to change your mind as new data emerge. Why did you choose to emphasize that?

Courtois: When students come to me to do an internship, they think I will give them a very specific subject and that I know what they will do Week 1, Week 2, Week 3, Week 4. … I tell them I will give them a question, and we are going to work on this question, and at the end of 2-3 months, we will have more questions than we had at the start. But they are so happy, because the more questions you have that means you found a little bit of the answer along the way and the question is getting more and more interesting. The first question is sometimes very broad, but then it's all the small questions that are the most interesting. I wanted to explain this.

Related: 8 Modern Astronomy Mysteries Scientists Still Can't Explain

Space.com: So, getting to the science of the book, your discovery of our supercluster depended on something called the Great Attractor. What is it?

Courtois: The Great Attractor is a place in the universe, not very far from us. All galaxies [in our supercluster], including ours, are converging in this direction. But it's a place we can't observe. [The Great Attractor lies in the "Zone of Avoidance," in which a profusion of gas and dust makes it impossible to see anything.] For example, [imagine that] you want to peer into the living room of your neighbor because it's very interesting — but you have a tree in front of your window, so you can't observe the living room directly. It's a little bit annoying. We call it the Great Attractor because the galaxies are moving very fast in this direction.

Sometimes people would ask me where I can look with my binoculars or my telescope to see Laniakea. And I would tell them it's everywhere around you —- Northern Hemisphere, Southern Hemisphere. If you want to look at Laniakea, it's the most difficult to find, because we're inside it.

Space.com: You also discuss a concept called "peculiar velocity." What are peculiar velocities, and how did they help identify Laniakea?

Courtois: Peculiar velocities are the velocities of galaxies which are due to gravitation. Mass attracts another mass. Peculiar velocity is the velocity due to the mass which is distributed around a galaxy in the universe. And we have to be careful, because the universe is expanding — but it's not a real velocity when a galaxy is going away from another galaxy due to expansion.

For example, let's say you have a checkered tablecloth in the bistro cafe, and you have two pints of beer sitting on the tablecloth, and if you stretch the tablecloth so all the squares will expand and the two pints will go away one from the other because you are stretching the tablecloth. So this is expansion — but actually we don't care about this. It's very easy to remove this velocity, because it’s just the space-time of the grid underneath which is expanding. It's not a physical velocity, actually. But with the two pints of beer, they have a mass and they want to become closer to each other, so they are attracted. We want to measure this very small velocity of attraction — this is the peculiar velocity. [Researchers calculated peculiar velocities for every galaxy in our supercluster relative to Earth. As the researchers noted when announcing Laniakea, "a map of peculiar velocities can be translated into a map of the distribution of matter." This is what they did to discover the extent of Laniakea.]

In writing the book, I was thinking that I should write "gravitational velocity," but peculiar velocity is the term we use in science.

Space.com: What's the most exciting thing on the horizon for your research?

Courtois: When you find just one supercluster, of course, there's one question — are we right or are we wrong? We have now found 10 superclusters, so we are very reassured that what we're doing is correct.

Now, the big question I have with my team is: What is gravitation, and why do galaxies in other superclusters fly so fast? We may need to change the language of how we describe velocity — we may need to change the equations of gravitation.

At the moment, 50% of physicists think we should look for invisible matter. I never call it "dark matter," because if it was dark, we could see it. Not only do we want to understand gravitation, we want to understand acceleration of the expansion of galaxies. I always say acceleration of the expansion instead of "dark energy" because it's not dark — if it was dark energy, we would see it. For now, the best term is acceleration of the expansion.

Space.com: Toward the end of the book, you say, "Science isn't solemn." Please expand on that.

Courtois: You can be happy doing this job. People think science is so serious, and it's not the way I am living my job, and it's not the way my colleagues are living their job. My colleague Brent Tully, at the University of Hawaii, says that we "play seriously." The universe is so beautiful, and I can understand how this beauty is put together — it's playful, it's joyful, lots of happiness doing science.

If you understand something and it stays in your drawer, it's the same as not understanding it if it's just for you. If you die, it's not new knowledge for humanity. The only way to make science advance is to tell everybody!

This interview has been edited for length and clarity. You can buy "Finding Our Place in the Universe" on Amazon.com.

- This 3D Color Map of 1.7 Billion Stars in the Milky Way Is the Best Ever

- Meet Hyperion: Colossal Supercluster in the Early Universe

- Supercluster of Galaxies Space Wallpaper

Follow Marcus Banks on Twitter @marcusabanks. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Marcus is an economic sociologist whose research interests encompass how labour, welfare and finance market risks are experienced in low income households, consumer credit and welfare, gender segmented labour markets, behavioral economics, and the sociology of money. He's also currently the Senior Research Fellow (casual), Better Work and Wellbeing Group, College of Business and Economics, University of Tasmania.