Hypersonic missile defense program moves toward 2 prototypes

The need for speed is real when it comes to missile defense.

The Department of Defense's Missile Defense Agency (MDA) has selected Northrop Grumman and Raytheon Missiles and Defense to continue developing prototypes of a Glide Phase Interceptor (GPI), a planned next-generation countermeasure to defend against hypersonic weapons.

While there are several different classes of hypersonic weapons that differ significantly, hypersonic weapons are typically defined as those that travel at Mach 5 or faster, or greater than five times the speed of sound. While it remains unknown what form the GPI will take, concept art typically depicts the interceptor as a rocket-boosted missile, although its exact payload is unknown.

A new contract modification published by MDA last week now brings the total value of the contracts awarded to Raytheon and Northrop Grumman to over $60 million. That funding is intended to allow the contractors to develop their designs in advance of a February 2023 review of a prototype hypersonic interceptor.

In a press release, Northrop Grumman's vice president of launch vehicles, Rich Staka, said "GPI will play a central role in ensuring the United States maintains the most reliable and advanced missile defense systems in the world that are capable of outpacing and defeating evolving missile threats." Meanwhile, Raytheon's announcement noted that the company will use digital engineering tools that allow for more rapid, less expensive development and will build on existing systems and technologies in their design.

Related: The US military just launched 3 rockets from a NASA center to boost hypersonic weapons research

The MDA wants to build a multi-layered defense system that links space-based sensors, ground-based radar, and various military weapons systems together in a singular network that will identify, track and attempt to intercept and destroy hypersonic targets.

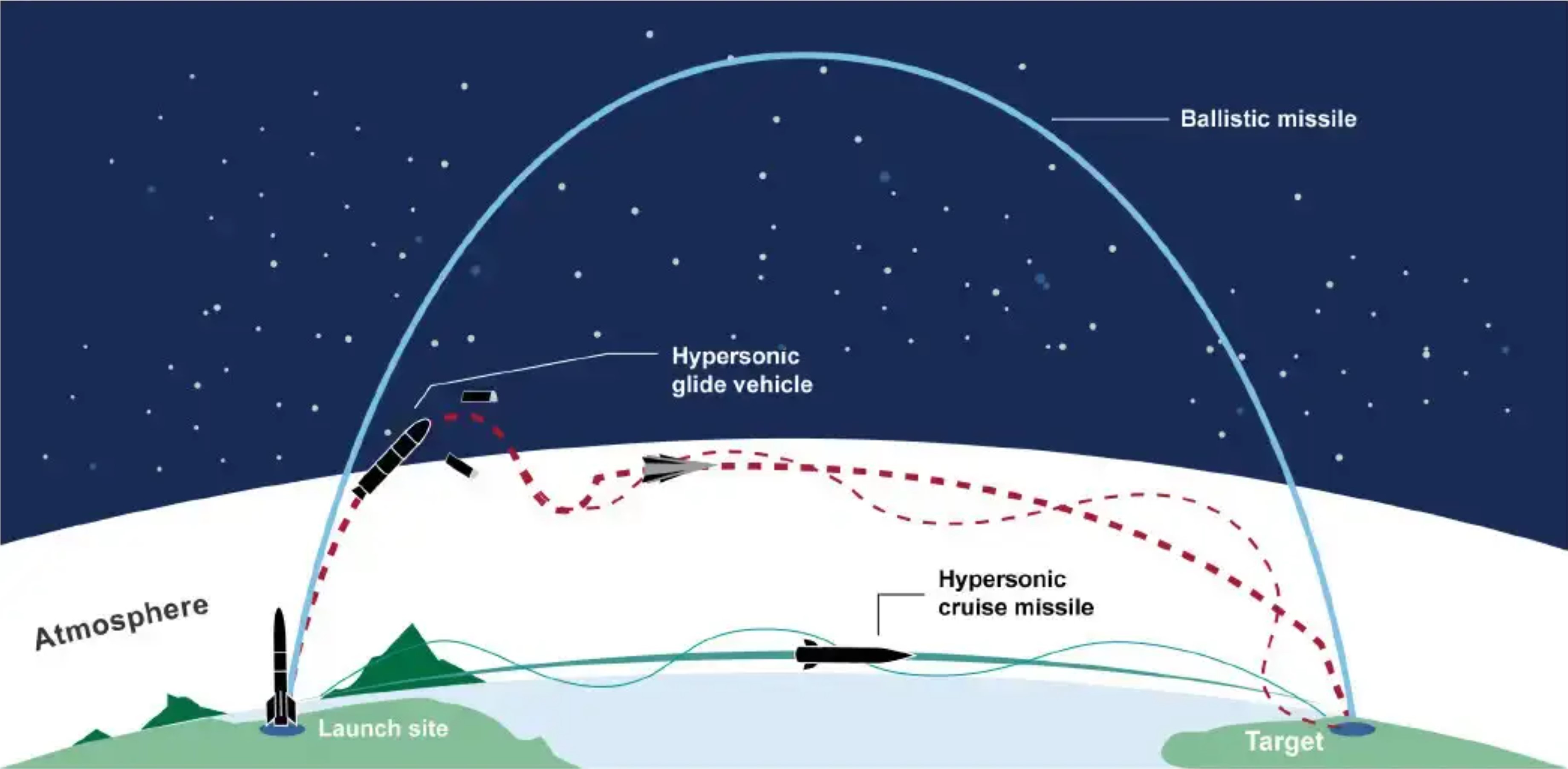

Some hypersonic weapons, known as boost-glide vehicles, are much more difficult to track than ballistic missiles due to their unique flight characteristics. After a rocket boosts such a hypersonic weapon to a desired speed and altitude, these vehicles are then released into the atmosphere. In flight, these vehicles travel at low altitudes at speeds multiple times faster than the speed of sound but they can also execute abrupt maneuvers, including changing their trajectories. It's this combination of speed and maneuverability that makes hypersonic glide vehicles so difficult to defend against — and why the MDA wants a capable interceptor to defeat these threats during this phase of flight.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The United States Air Force announced its first successful hypersonic weapon test in May 2022, but several foreign nations have already demonstrated hypersonic weapons that could pose a threat to America's current missile-defense systems. China has tested several hypersonic missiles, while even North Korea has claimed to have tested their own hypersonic glide vehicles. Russia even claims it has used the dizzyingly fast weapons against Ukraine during its current invasion.

Given these claims, it's no wonder that the Missile Defense Agency requested $225 million for hypersonic defense programs in its budget request for fiscal year 2023, which begins Oct. 1. If either company participating in the Glide Phase Interceptor program can produce a viable prototype with the new funding, the Pentagon would be one step closer to its vision for defending against this terrifying class of weapons.

Email Brett at BTingley@Space.com or follow Brett on Twitter at @bretttingley. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Brett is curious about emerging aerospace technologies, alternative launch concepts, military space developments and uncrewed aircraft systems. Brett's work has appeared on Scientific American, The War Zone, Popular Science, the History Channel, Science Discovery and more. Brett has English degrees from Clemson University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. In his free time, Brett enjoys skywatching throughout the dark skies of the Appalachian mountains.