A space laser is tracking subglacial lakes hidden in Antarctica

ICESat-2 has discovered more subglacial lakes.

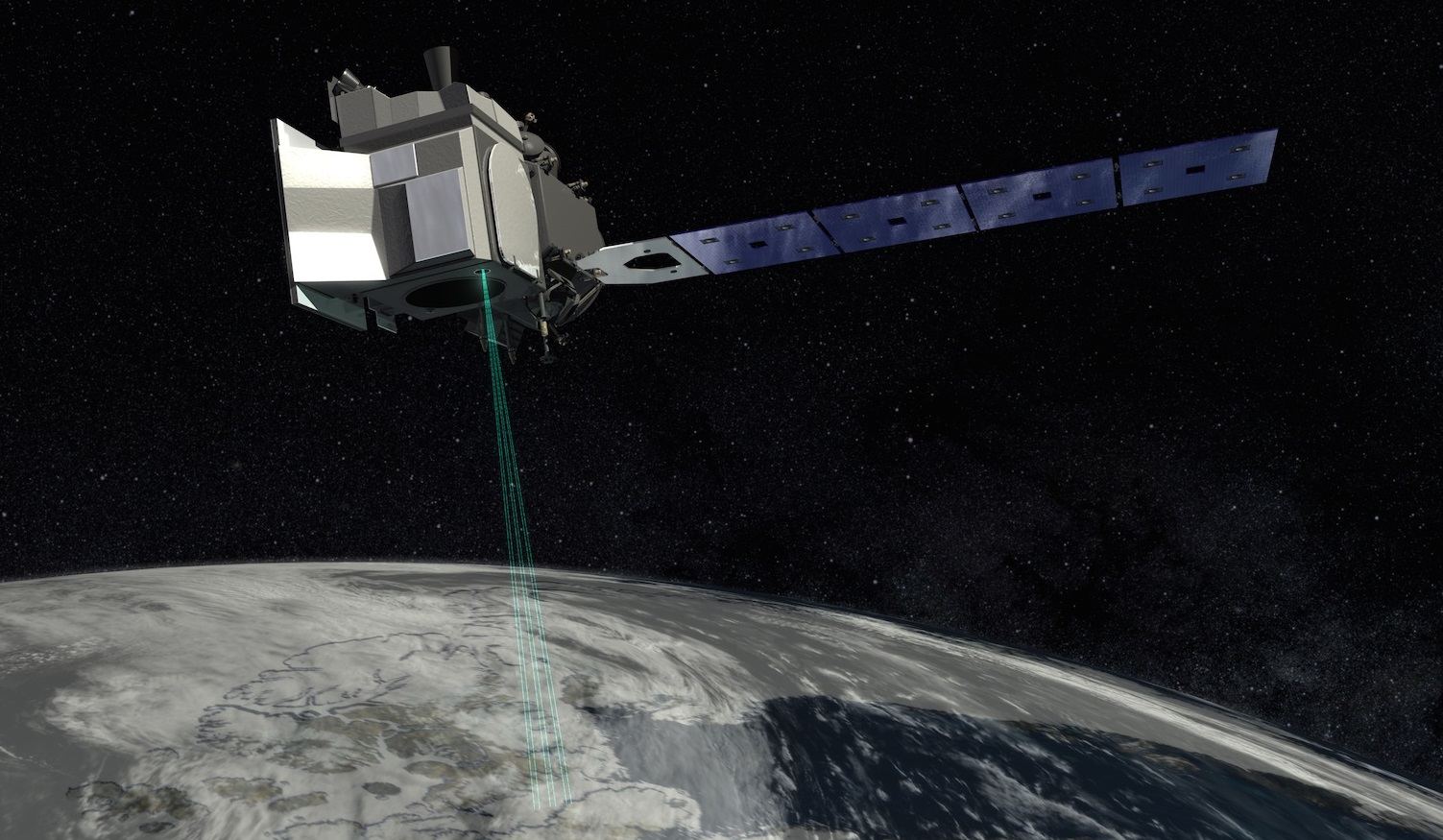

A NASA satellite in space that shoots a laser beam down to Earth has spotted still more subsurface lakes sandwiched between Antarctica's land and ice.

Antarctica is land with hundreds of feet or meters of ice sitting atop it. In between these two layers, elements such as the friction from the ice and the continental bedrock, fluctuations in how much downward pressure the ice exerts, and heat released from Earth creates hundreds of hidden lakes. These pocket lakes are dynamic, too: In 2007, glaciologist Helen Amanda Fricker used data from NASA's Ice, Cloud and land Elevation Satellite (ICESat) to discover that these lakes fill and drain via a network of subglacial waterways.

ICESat retired in 2010m, but its successor, ICESat-2, has picked up where the earlier mission left off, including discovering more subglacial lakes, according to a NASA statement.

Related: Watch this giant iceberg break off from Antarctica

The discovery of these interconnected systems of lakes at the ice-bed interface that are moving water around, with all these impacts on glaciology, microbiology and oceanography — that was a big discovery from the ICESat mission," Matthew Siegfried, geophysicist and lead investigator of a new study published July 7 in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, said in the statement.

"ICESat-2 is like putting on your glasses after using ICESat," he added.

The changing volume and shape of these subglacial lakes impacts the elevation of the ice above them. ICESat-2 tracks the rise and fall of the Antarctic surface elevation to help scientists figure out what's happening to the otherwise invisible lakes underneath the ice.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Related: 'Last Ice Area' in the Arctic may not survive climate change

The Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System (ATLAS) is the only instrument on ICESat-2. It measures how long it takes for its laser beam to bounce back into space from Earth. If the laser hits a tall land feature, the light takes less time to reach space than it would have if it hit a low-lying regio so, this technique helps scientists monitor elevation changes to landscapes. ATLAS' highly-precise time measurements can count to a billionth of a second, the equivalent of centimeters in elevation, according to NASA.

Like its acronym suggests, ICESat-2 is a mission to study the frozen water parts of the world known as the cryosphere, which includes ice sheets, permafrost, the snow caps on mountains and winter snow cover. The cryosphere is vital to cooling down Earth, storing and slowly releasing fresh water and preventing sea levels from rising.

Antarctica is one of the most important segments of the cryosphere, and what happens there has consequences for the rest of the planet.

And the continent's hidden subglacial lakes matter because they release water into the sea via a series of natural drainage waterways, according to NASA. The amount of water released into the ocean by these lakes and channels, as well as how this water flows along ocean currents, are important details that scientists need to monitor to develop a big-picture understanding of Antarctica as climate change intensifies.

"It's not just the ice sheet we're talking about," said Siegfried. "We're really talking about a water system that is connected to the whole Earth system."

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.