Astronomers pierce cosmic dust of 'Jewel Bug Nebula' to study anatomy of a dying star

A brand new spectrograph on the Gemini North telescope has seen first light, detecting elements in a dying star known as the Jewel Bug Nebula.

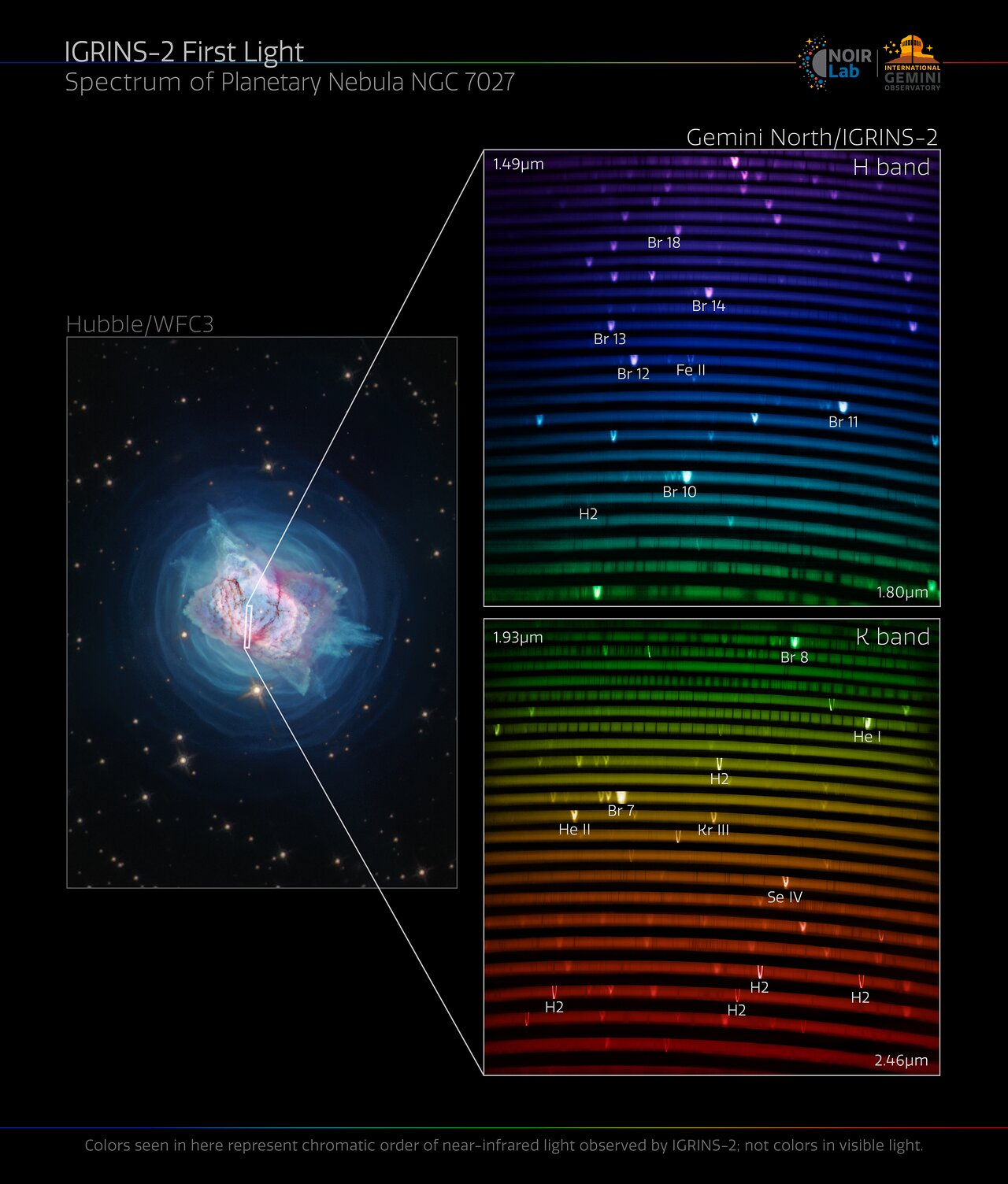

Astronomers with the Gemini North Telescope on Mauna Kea in Hawaii have released the first spectrum from a brand new spectrograph capable of peering deep into the veils of cosmic dust that line our universe.

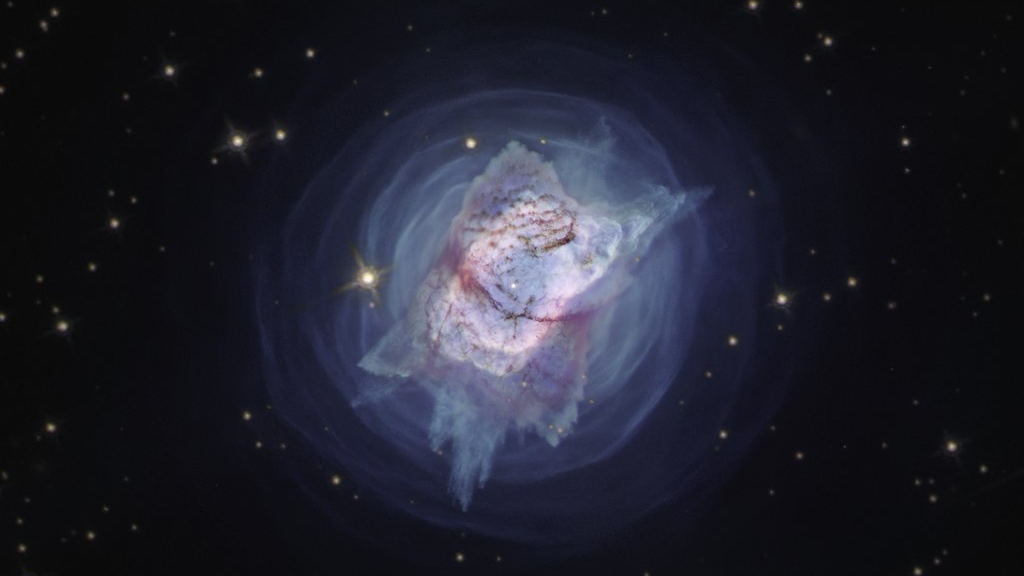

The spectrum shows details of an expanding cloud of gas and dust that a sun-like star ejected at the end of its life. This cloud is known as a planetary nebula — perhaps a misleading name as it doesn't have anything to do with planets. More specifically, this nebula is formally called NGC 7027, or the Jewel Bug Nebula, and sits about 3,000 light years away from us in the constellation of Cygnus, the Swan.

The new spectrograph that managed to observe the light of the Jewel Bug Nebula is named IGRINS-2, which is short for Immersion Grating Infrared Spectrograph-2. It’s a high-resolution instrument that operates at near-infrared wavelengths of light — wavelengths unseeable by human eyes — specifically between 1.45 and 2.45 microns. Cosmic dust is opaque at visible wavelengths, which our eyes can see, but near-infrared light can penetrate through that dust and detect what secrets lie beneath. That’s why the James Webb Space Telescope is also said to have the ability of peering behind deep space dust curtains. It's the most powerful near-infrared wavelength detector we have.

Related: Scientists catch real-life Death Star devouring a planet in 1st-of-its-kind discovery

As for the "immersion grating" bit, this is a kind of diffraction grating that uses transparent and reflective mediums to split light into its component wavelengths. That's what IGRINS-2 did with the infrared wavelengths to achieve the vibrant, detailed spectrum we see.

IGRINS-2 is an updated version of the original IGRINS spectrograph, built in 2014 by scientists at the Korea Astronomy and Space Science Institute (KASI) as well as the University of Texas.

IGRINS 1.0 has already been around the block, with periods of being installed as a "visiting instrument" on a number of telescopes including the 2.7-meter (8.9 feet) Harlan J. Smith Telescope at McDonald Observatory in Texas, and the 4.3-meter (14.1 feet) Discovery Channel Telescope at Lowell Observatory in Arizona. And since 2020, IGRINS has been installed on the 8.1-meter (26.6 feet) Gemini South Telescope in Chile.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Now, the other half of NOIRLab’s International Gemini Observatory, namely Gemini North, is receiving IGRINS-2 — and on a permanent basis.

Built once more by scientists and technicians at KASI, the first-light spectrum of the Jewel Bug Nebula is only the beginning. Following a period of integrating the instrument into Gemini North’s sub-systems and getting it to work with the telescope’s software, IGRINS-2 will primarily target regions of star-birth, as well as star-death in the case of NGC 7027, exoplanets, cool brown dwarfs that radiate mostly in the infrared, and distant galaxies swathed in dust during some of the more tumultuous stages of their evolutions.

"The ability of IGRINS-2 to peer within otherwise opaque regions of the universe will allow us to better understand how stars are born and many other astronomical phenomena hidden behind galactic dust," Martin Still, the National Science Foundation's Program Director for the International Gemini Observatory, said in a statement.

IGRINS-2 identified elements such as isotopes of bromine, helium, iron, krypton and selenium in NGC 7027, plus copious amounts of molecular hydrogen. With the powerful light-gathering capability of Gemini North’s 8.1-meter mirror at its disposal, we can expect IGRINS-2 to make even more detailed observations and many major discoveries in the future.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.