'Immortal stars' could feast on dark matter in the Milky Way’s heart

These stars might be using dark matter as fuel.

"All good things must come to an end." That adage holds true in the cosmos as well as on Earth.

We are aware that stars, like everything else, must die. When they run out of the fuel supply needed for nuclear fusion at their cores, stars of all sizes collapse under their own gravity, dying to form a dense cosmic remnant like a white dwarf, a neutron star, or a black hole. Our own star, the sun, will meet this fate in around 5 billion years, first swelling out as a red giant and obliterating the inner planets, including Earth. After around 1 billion years, this phase, too, will end, leaving the core of the sun as a white dwarf ember surrounded by a cloud of cosmic ashes in the form of cooling stellar material.

Scientists have developed the Hertzsprung-Russell diagram, a chart of stellar life, afterlife and death. This diagram tracks stars of all masses through their evolution from main sequence hydrogen-burning stars to dense cosmic remnants.

However, new research has revealed that some stars at the heart of our galaxy may be thumbing their noses at our best models of stellar life and death. These stars could be feeding on dark matter, the universe's most mysterious stuff, to effectively grant themselves cosmic immortality, thus necessitating the creation of a "dark Hertzsprung-Russell diagram."

Related: Across the universe, dark matter annihilation could be warming up dead stars

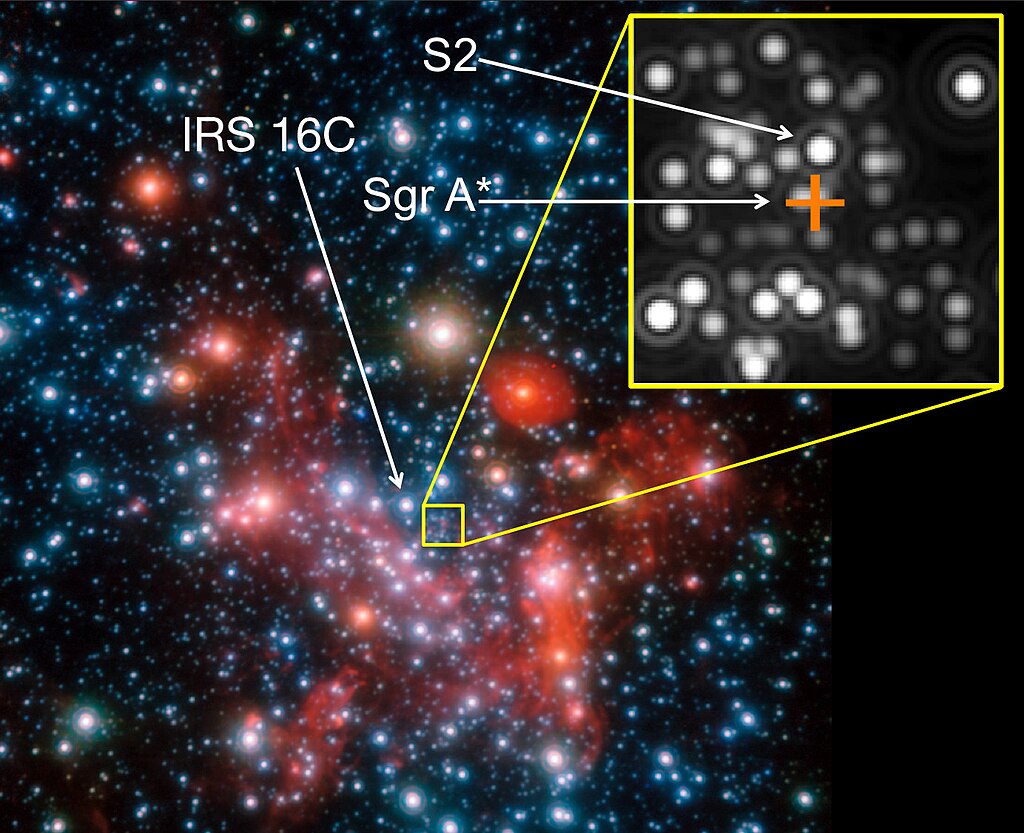

"The Galactic Center of the Milky Way is a very extreme environment and very different from our location in the Milky Way," research team leader Isabelle John of the Kavli Institute for Particle Astrophysics and Cosmology told Space.com. "The stars closest to the Galactic Center, the so-called 'S-cluster stars,' are very puzzling.

"They show a series of properties that are not found anywhere else: It is not clear how they got so close to the center, where the environment is thought to be rather hostile to star formation."

John added these S-cluster stars, which lie within around three light-years of the very heart of our galaxy, also seem to be much younger than would be expected if the stars had migrated to this region from elsewhere in the Milky Way. "Even more mysteriously, not only do the stars look unusually young, but there are fewer older stars than expected," she continued. "Additionally, it seems like there are unexpectedly many heavy stars."

John and colleagues postulate that a reason for these unusual features could be that these stars gather large amounts of dark matter, which then annihilates within them. This process could provide them with an entirely new and unexpected form of fuel.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Our simulations show that stars can survive on dark matter alone as fuel, and because there is an extremely large amount of dark matter near the Galactic Center, these stars become immortal," John added. "This is quite fascinating because our simulations show similar results to the observations of S-cluster stars: Dark matter as a fuel will keep stars forever young."

"The idea of immortal stars," John continued, "can explain many of the unusual properties of the S-cluster stars at once. If stars at the Galactic Center become immortal due to the high dark matter density, this can account for the unusually large abundance of seemingly young stars at the Galactic Center while simultaneously explaining the lack of older stars."

Dark matter is its own worst enemy

Dark matter is a problem for physicists because, accounting for an estimated 85% of the universe, it is invisible to us because it doesn't interact with light. Additionally, dark matter doesn't seem to interact with "ordinary matter." This everyday matter is made up of protons, neutrons, and electrons and it comprises all the stars, planets, moons, asteroids, comets, gas, dust, and living things in the universe.

Scientists can only infer the presence of dark matter because it interacts with gravity, and this interaction can affect ordinary matter and indeed light. If interactions between dark matter and ordinary matter do happen, however, these are rare and weak; scientists don't believe we've never detected such an interaction.

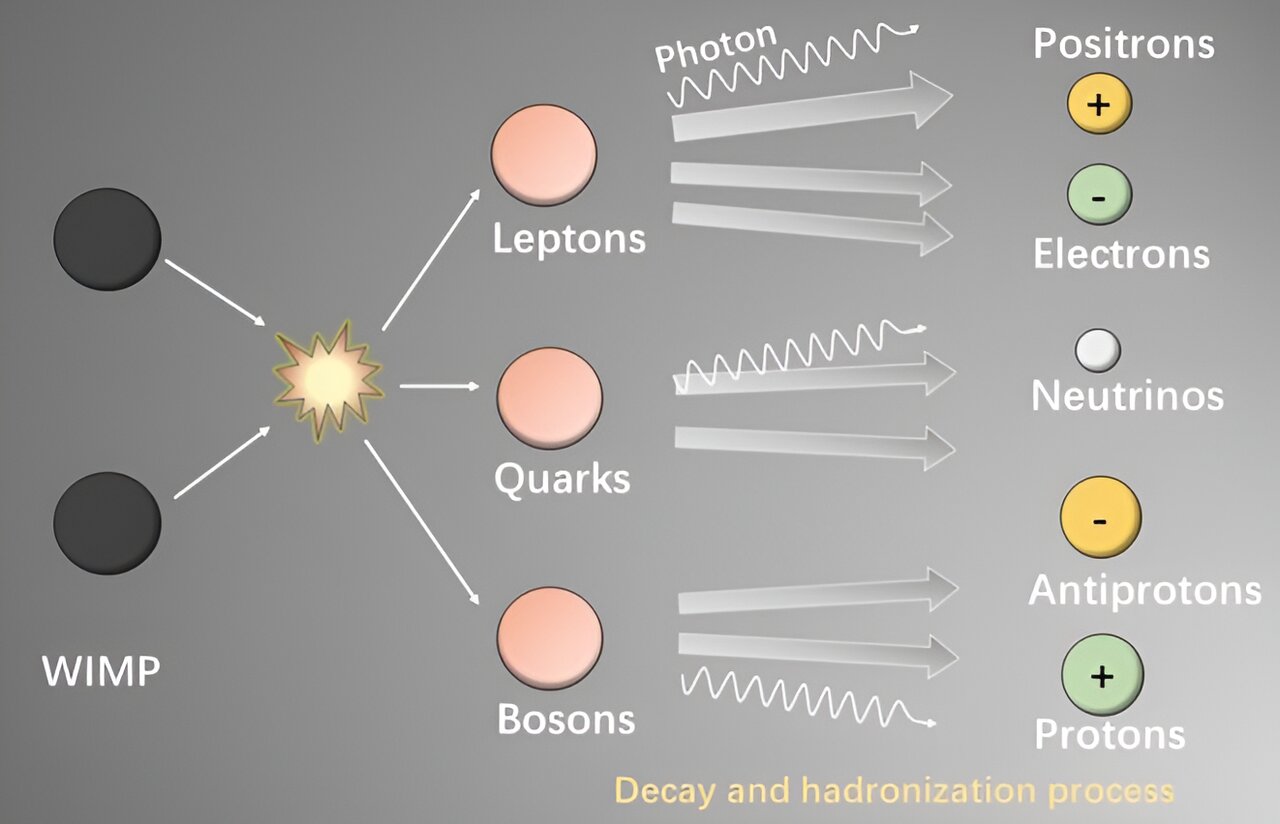

What is less certain is whether dark matter interacts with itself. To understand what this means, remember that ordinary matter particles all have an antimatter version of themselves. For instance, there is a positively charged antiparticle called a positron for a negatively charged electron. And when matter and antimatter meet, they annihilate each other, releasing energy.

"Dark matter annihilation is analogous to the annihilation of matter and antimatter: if a particle and its antiparticle meet, they get destroyed and produce other particles, for example, photons. Similarly, dark matter particles could annihilate in such a way," John said. "In many dark matter models, the dark matter particles are considered to be their own antiparticle, which means that any two dark matter particles can annihilate with each other."

We don't see dark matter annihilation, however, so it must be fairly rare. That means, John says, it would be more likely to occur in an environment where huge amounts of dark matter can be crammed together. Maybe the ultradense region at the heart of a star is where gravity, which dark matter does interact with, is strongest.

Could the sun become immortal too?

Main sequence stars burn hydrogen in nuclear fusion processes during their lifetimes. This creates helium, the majority of the star's energy, and the outward "radiation pressure" that balances out the inward push of the star's own gravitational forces. This cosmic tug-of-war between radiation pressure and gravity lasts for millions, or even billions, of years and keeps these stars in stable equilibrium.

"For most of a star's life, these processes happen primarily in the core of the star, where the gravitational pressure is highest," John said. "We show that if stars collect a large amount of dark matter, which then annihilates inside the star, it can also provide an outward pressure, making the star stable due to dark matter annihilation rather than nuclear fusion. So, stars can use dark matter as a fuel instead of hydrogen.

"Stars use up their hydrogen, which will eventually cause them to die. On the other hand, dark matter can be collected continuously, which makes these stars immortal."

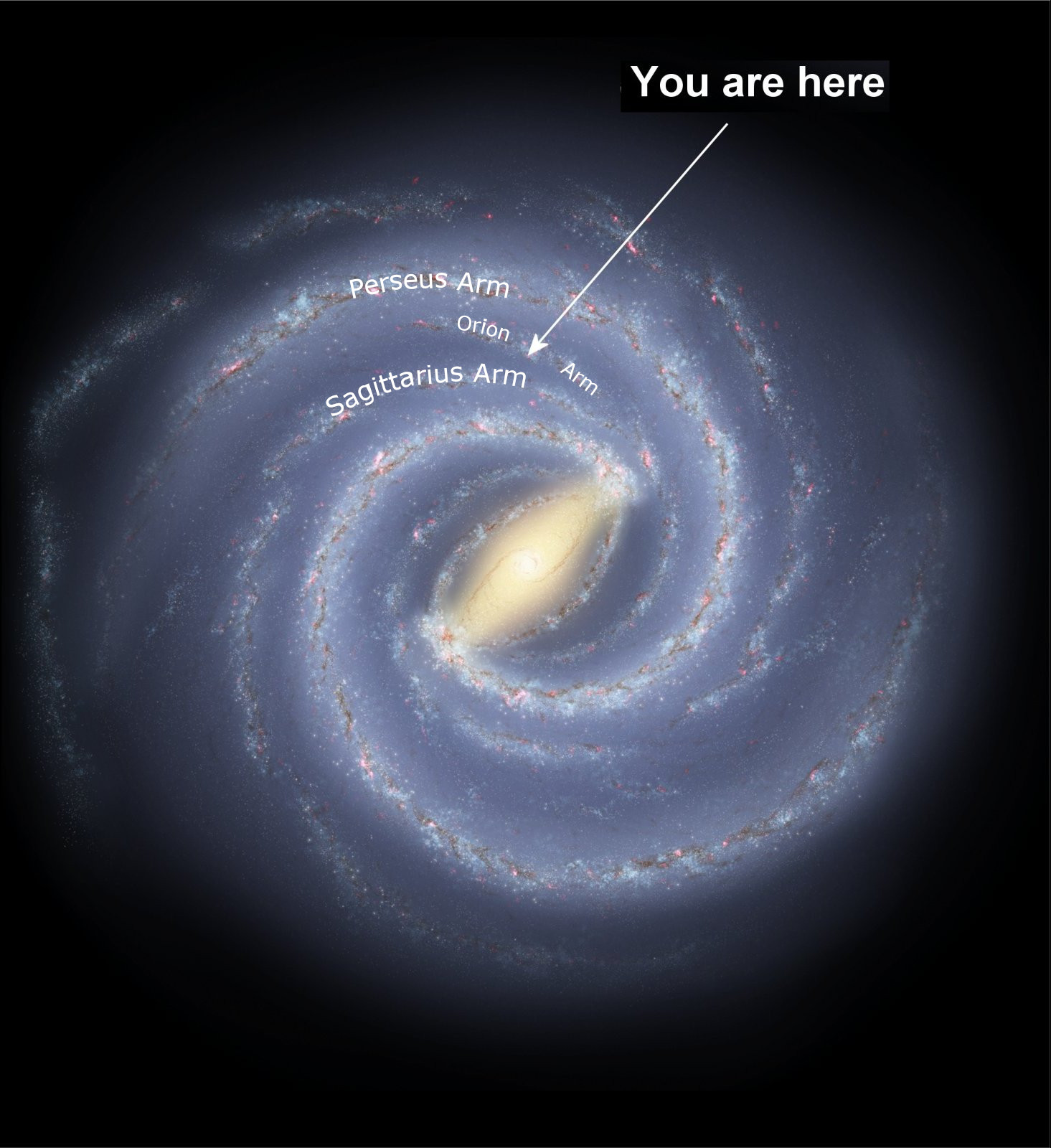

So, could the sun grant itself immortality by switching to this alternative fuel source? John thinks not. Located midway out on one of the Milky Way's spiral arms, it is just in the wrong spot in our galaxy to access this dark fountain of youth.

"Stars need very large amounts of dark matter to efficiently replace fusion. Throughout most of the Milky Way, the dark matter density is not high enough to affect stars significantly. But at the Galactic Center, the density of dark matter is very high, potentially many billion times higher than on Earth, which provides the amount of dark matter needed to make stars immortal," Jon explained. "So, our sun is not immortal."

John added that the team's findings potentially indicate many secrets about dark matter itself as well as the immortal stars it could power.

"Our findings tell us that dark matter can scatter with ordinary particles, which is required to slow down the dark matter particles inside the star to capture them — also, that dark matter particles can annihilate with each other," she said. "By observing the distribution of immortal stars around the Galactic Center, we would also get some information about the distribution and density of dark matter around the Galactic Center."

John explained that, to verify these findings, astronomers need more precise observations of the innermost stars of the Milky Way to determine whether these stars lie in a "dark main sequence," which could hint towards their immortality.

They also intend to determine the effect of dark matter annihilation on different stars. Initial simulations indicate that lighter stars would become "puffy" and shed their outer layers when they switch to this dark fuel. This could explain the nature of so called "G-objects" found at Galactic Center, which are stellar bodies that appear to be surrounded by clouds of gas.

"So far, our work has focused on main sequence stars. We also want to understand how dark matter affects stars at later evolutionary stages when they have moved away from the main sequence and undergo different nuclear fusion processes," Johns said. "Our results are exciting because they show that stellar observations offer an additional and unique way of studying and understanding the interactions of dark matter with ordinary matter."

A pre-peer-reviewed version of the team's research is available on the paper repository arXiv.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

-

rod The ref paper abstract states, "Abstract We show that stars in the inner parsec of the Milky Way can be significantly affected by dark matter annihilation, producing population-level effects that are visible in a Hertzsprung-Russell (HR) diagram. We establish the dark HR diagram, where stars lie on a new stable dark main sequence with similar luminosities, but lower temperatures, than the standard main sequence. The dark matter density in these stars continuously replenishes, granting these stars immortality and solving multiple stellar anomalies. Upcoming telescopes could detect the dark main sequence, offering a new dark matter discovery avenue."Reply

*dark HR diagram*, something different than the standard HR diagram to explain the stars seen in the report. "The dark matter density in these stars continuously replenishes, granting these stars immortality and solving multiple stellar anomalies."

In the old days (I am old, 70 years) I understood p-p chain, CNO, and triple alpha process fusion for interpreting HR diagram plots, now I must rethink much and look at DM to the rescue explaining results that indicate potential problems with some stars observed now :) This stellar evolution paradigm should be interesting to follow as it develops. -

mokeshame This is the case but not entirely. The black holes in the center of our Galaxy have one purpose that is adding one dimension to the two that already exists. With this fenomenon an group of particles, let say our Milky Way can fuel itself for ever. But this doesnt say that the black whole will forever exist. It wil evolve eventually to a higher system state. Nature can entaganle itself and thus forms particle systems.Reply

The reason behind this is that the universe has one goal. That is to accelarate itself in the void. But in order to accalerate it cannot miss steps that caused its accelartion. This means from a philosofical view that our universe(reality) is never finished but well conserved at the same time. Thus accepting that the world around is more perfect we can possibly image. -

Unclear Engineer The many stories about "dark matter" seem highly speculative and somewhat inconsistent.Reply

For instance, let's assume that dark matter is its own antiparticle and can release energy by annihilating itself. Then, it must result in the release of energy that somehow affects regular matter. Otherwise, the regular matter would continue to behave as predicted by the Hertzsprung-Russell (HR) diagram, and we would have not idea that there were "immortal dark stars" except perhaps by their gravitational effects that we could observe. I guess those would look like black holes to us if they don't emit normal photons, but do suck them in. But, if they do emit normal photons, then why aren't we detecting some annihilations somewhere? We certainly are looking for them.

And, this hypothesis also seems to indicate that this "dark matter" can scatter off regular matter. Again. we should be able to detect that, because conservation of momentum tells us that the regular matter would appear to move in a way that has no observable cause. -

bwana4swahili A pretty far out research paper considering no one really knows if dark matter exists let alone whether it has any impact on star 'youth'!?Reply