India is on its way to the moon again — this time, to the lunar surface.

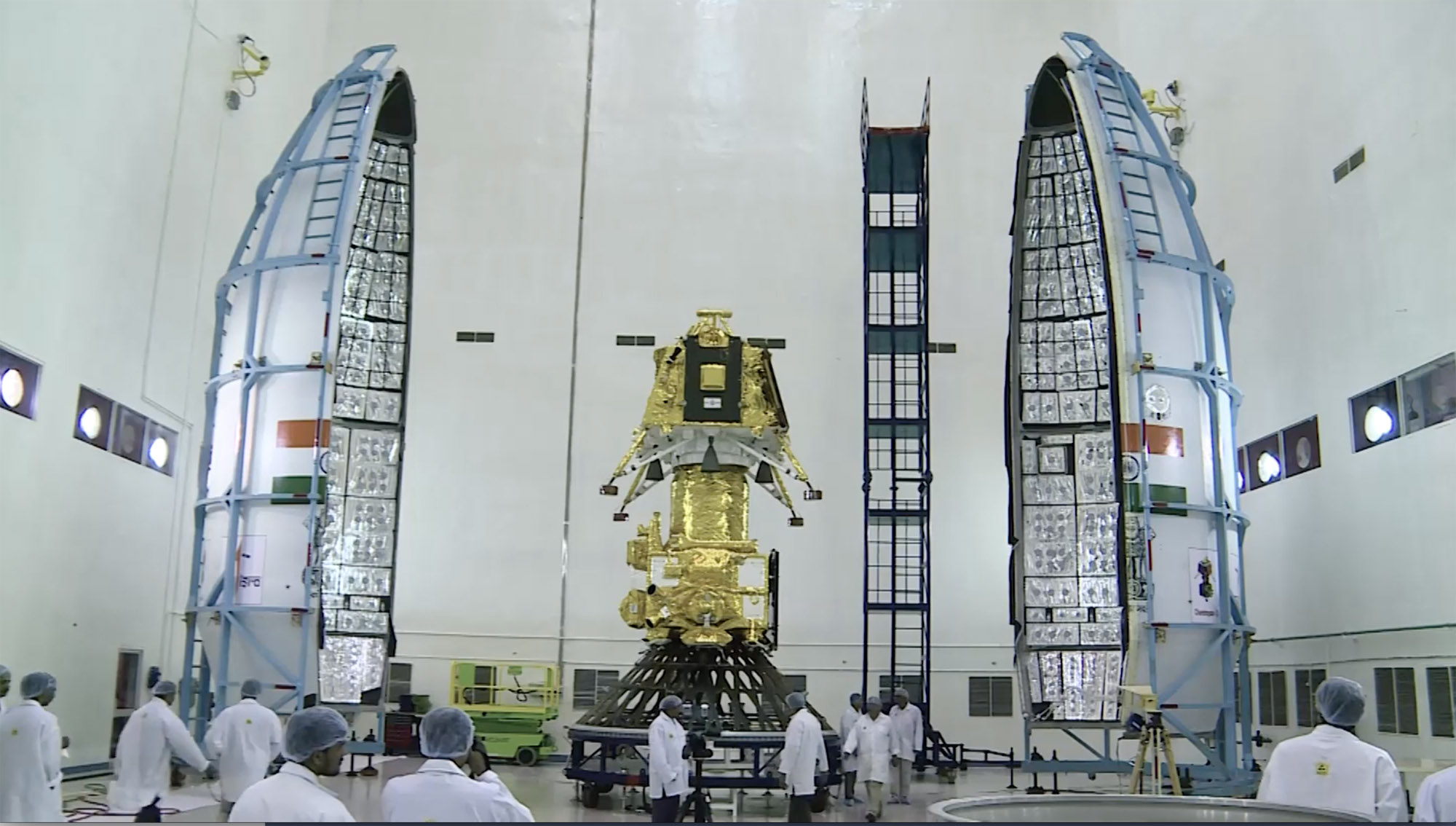

The nation's robotic Chandrayaan-2 mission launched today (July 22) from Satish Dhawan Space Centre, rising off the pad atop a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle Mark III (GSLV Mk III) rocket at 5:13 a.m. EDT (0913 GMT; 2:43 p.m. local Indian time). The launch came after just over a weeklong delay due to a rocket glitch, and just days after NASA celebrated the 50th anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing.

"My dear friends, today is a historical day for space and science technology in India," said K. Sivan, Chairman of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO), adding that the GSLV Mk III rocket placed Chandrayaan-2 in a better orbit than expected. "It is the beginning of a historical journey of India towards the moon and to land at the place near the south pole, to carry out scientific experiments, to explore the unexplored."

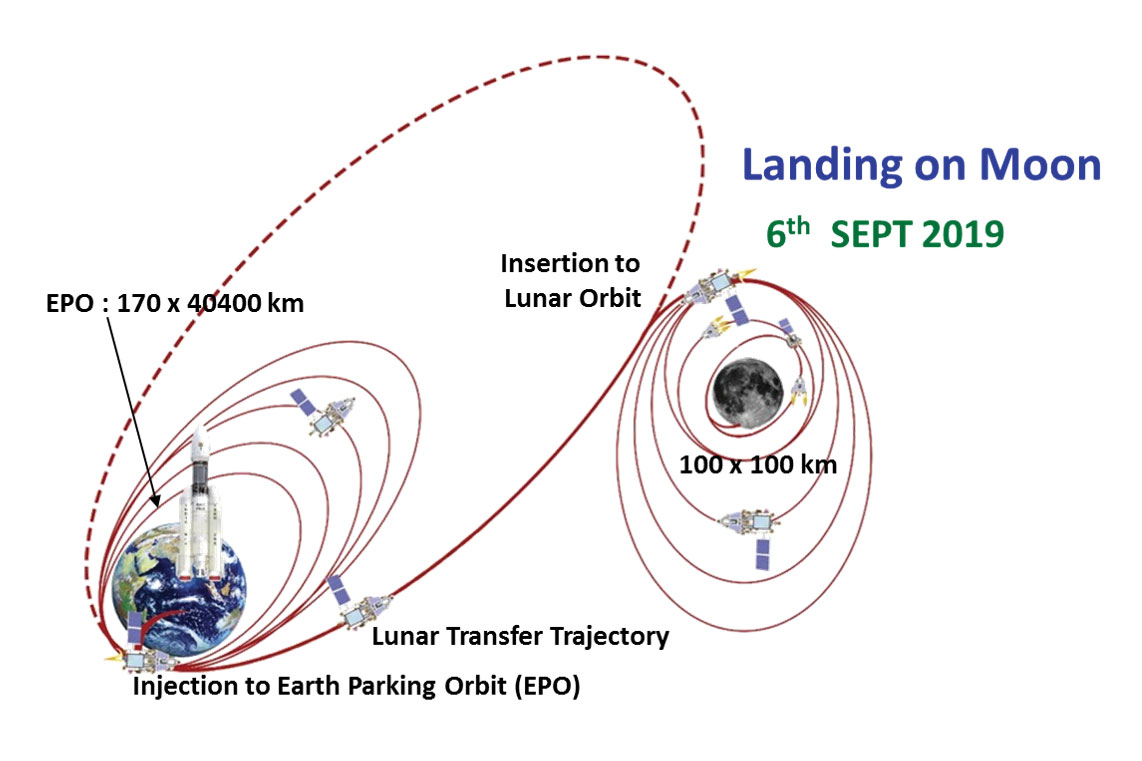

The liftoff kicks off a long and looping deep-space trip. If all goes according to plan, the spacecraft will reach lunar orbit on Sept. 6 and then put a lander-rover duo down near the moon's south pole shortly thereafter.

Related: The Science of India's Chandrayaan-2 Moon Mission

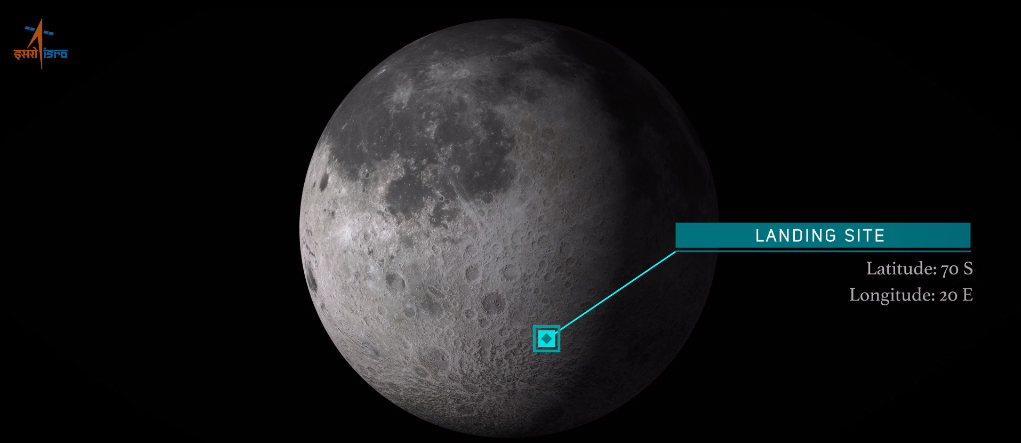

A successful touchdown would be historic; to date, only the United States, the Soviet Union/Russia and China have managed to soft-land a craft on the moon. And none of these touchdowns have been in the south polar region, which is believed to harbor huge amounts of water ice on the floors of permanently shadowed craters.

Chandrayaan-2 was originally scheduled to launch on July 14 but was delayed for eight days by an issue with the rocket.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A long time coming

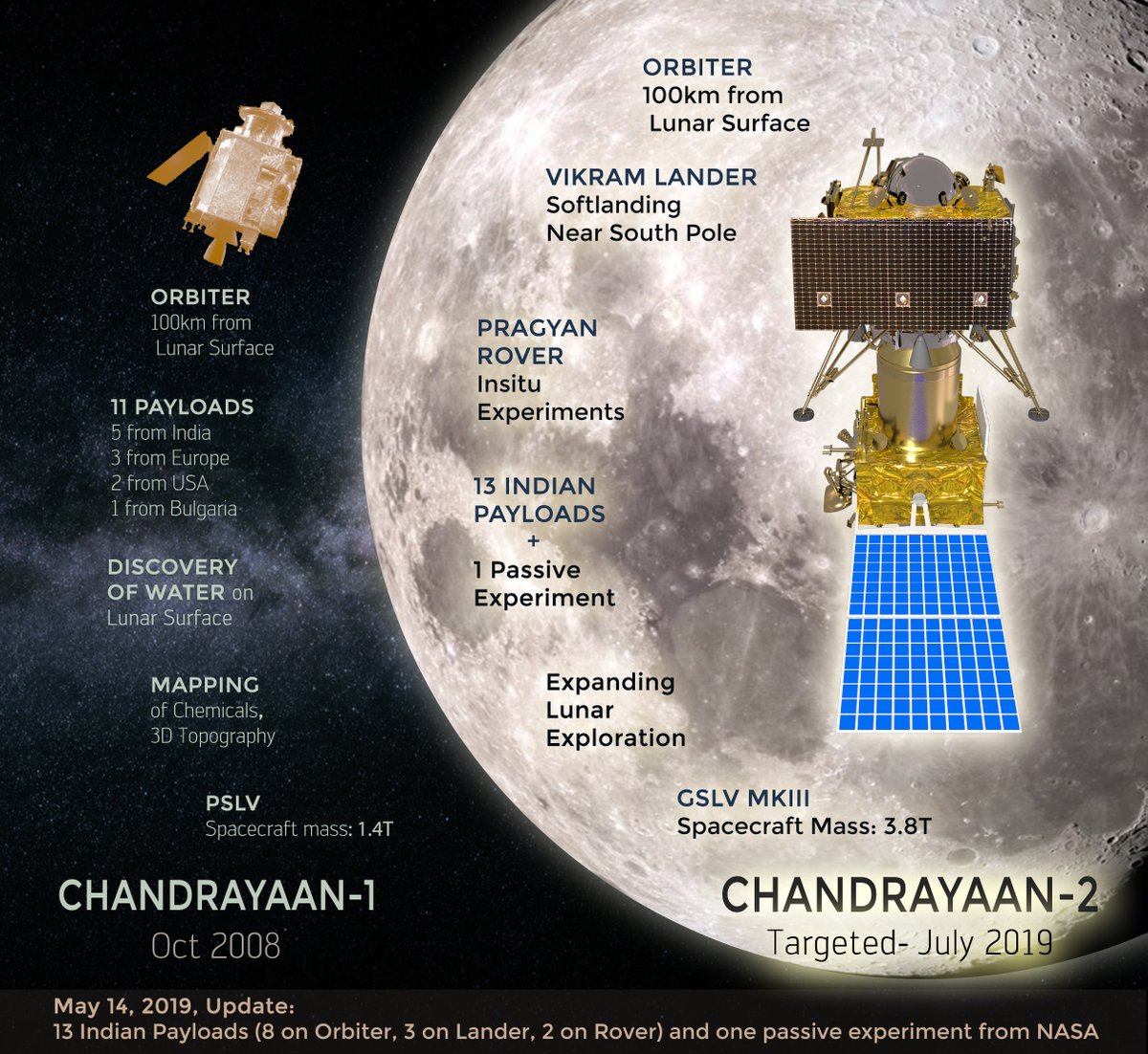

India already has one robotic moon mission under its belt: the successful Chandrayaan-1, which launched in October 2008 and operated through August 2009. Chandrayaan-1 consisted of an orbiter and an impactor, which slammed hard into the lunar south pole in November 2008. Both of these craft spotted evidence of water ice on the moon.

There wasn't supposed to be an 11-year wait for the second lunar trip; Chandrayaan-2 was originally scheduled to launch in 2013. And the mission began as a partnership with Russia, which was to supply the lander.

But things changed after the 2011 failure of Russia's Phobos-Grunt Mars mission, which never made it out of Earth orbit. Russia decided to perform an extensive review of Phobos-Grunt's gear, which included a lander. This resulted in significant delays, with Russian officials eventually stating they could not meet even a revised 2015 launch date for Chandrayaan-2. So, in 2013, India decided to cut ties with Russia and do everything in-house.

The cost of Chandrayaan-2 is around 10 billion rupees, officials with the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) have said. That's about $145 million at current exchange rates.

Lots of science gear

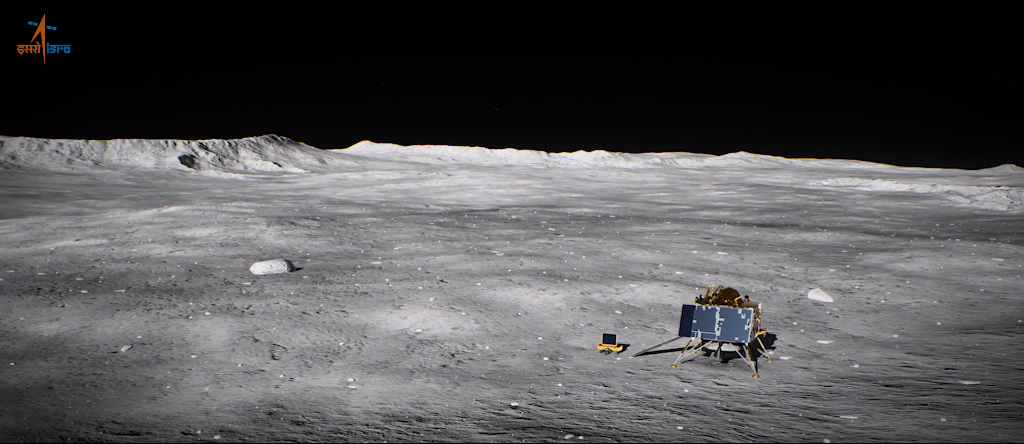

Chandrayaan-2 will settle into a circular orbit, 62 miles (100 kilometers) above the moon's surface. Eventually, the orbiter will deploy the lander-rover duo, which will touch down on a plain between the craters Manzinus C and Simpelius N, about 70 degrees south of the lunar equator.

The Chandrayaan-2 lander is named Vikram, after Vikram Sarabhai, the father of the Indian space program. The rover, called Pragyan ("wisdom" in Sanskrit), will roll down a ramp from Vikram onto the lunar surface. (Chandrayaan, by the way, means "moon vehicle" in Sanskrit.)

The six-wheeled, solar-powered Pragyan will be able to travel up to 1,640 feet (500 meters) on the lunar surface, ISRO officials have said. The rover will communicate only with the lander, which will be capable of beaming information both to the Chandrayaan-2 orbiter and directly to the Indian Deep Space Network here on Earth.

All three vehicles are packed with scientific gear. The orbiter carries eight scientific instruments, including multiple cameras and spectrometers; Vikram is outfitted with four instruments and Pragyan two.

All of these payloads were developed by Indian scientists, except one: a passive experiment from NASA called the Laser Retroreflector Array (LRA).

The LRA is designed to help researchers pinpoint the location of spacecraft on the lunar surface and calculate the distance from Earth to the moon precisely. An instrument of the same design also flew aboard Israel's Beresheet lander, which crashed during its lunar touchdown attempt in April.

Advancing exploration

The Chandrayaan-2 orbiter is designed to operate for one Earth year. Vikram and Pragyan, by contrast, are expected to work on the surface for just half of one lunar day — equivalent to about 14 Earth days. (The duo likely won't survive the long and cold lunar night.)

The data gathered by the three spacecraft should build upon the knowledge gained by Chandrayaan-1 and enable even more ambitious exploration down the road, mission team members have said.

"Through this effort, the aim is to improve our understanding of the moon — discoveries that will benefit India and humanity as a whole," ISRO officials wrote in a description of Chandrayaan-2. "These insights and experiences aim at a paradigm shift in how lunar expeditions are approached for years to come — propelling further voyages into the farthest frontiers."

India isn't alone in eyeing the moon's resource-rich south polar region. For example, NASA plans to land astronauts there in 2024, and build up a long-term, sustainable presence on and around the moon over the following years.

- The 21 Most Marvelous Moon Missions of All Time

- How NASA Scrambled to Add Science Experiment to India's Moon Probe

- ISRO: The Indian Space Research Organization

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.