Strange ingredient in interstellar Comet Borisov offers a clue to its origins

Astronomers have revealed the unusual chemical composition inside 2I/Borisov, the interstellar comet that visited our solar system last year. A strange ingredient has provided new clues about where this traveling space rock originated.

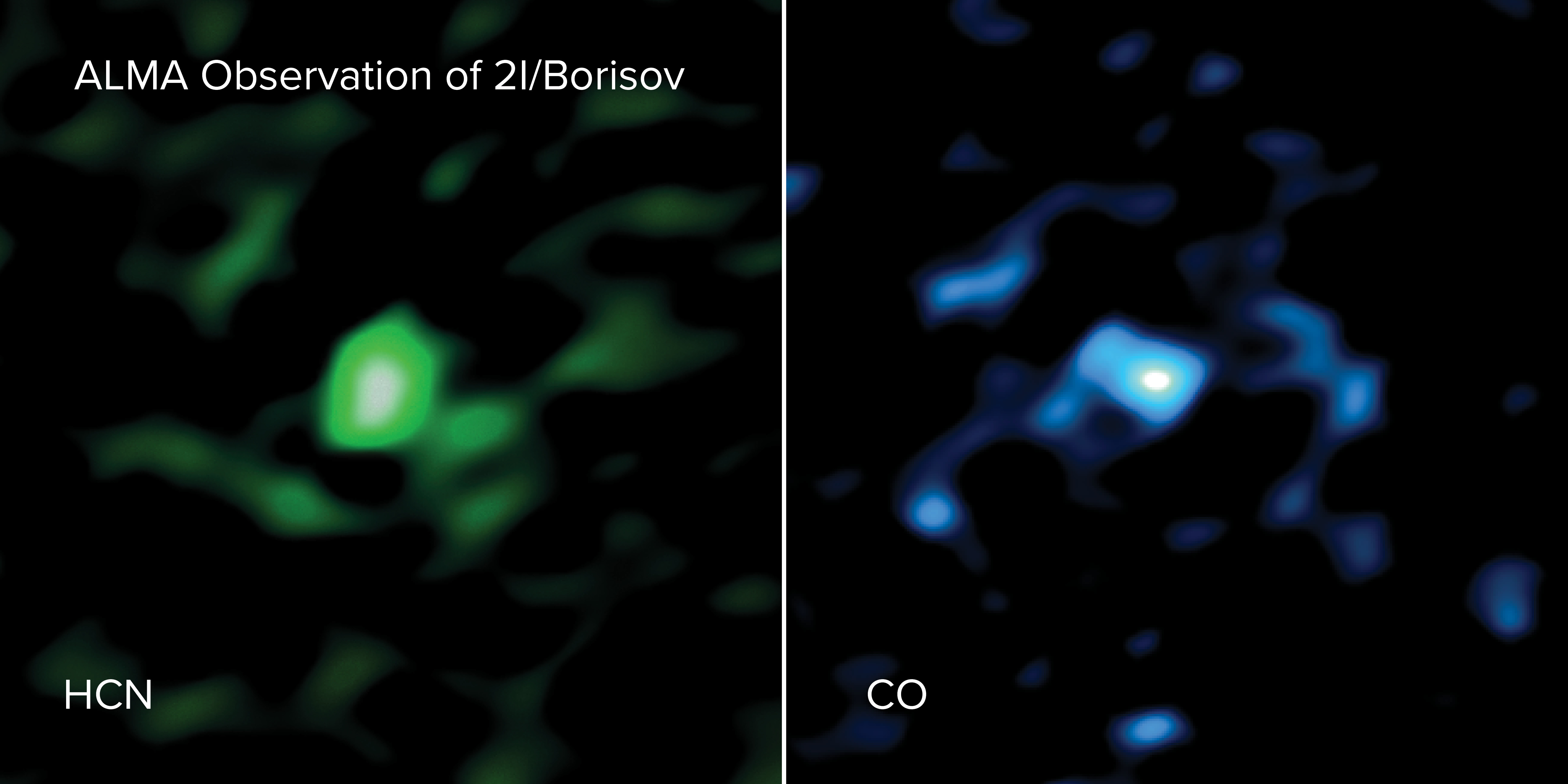

2I/Borisov was discovered on Aug. 30, 2019, by amateur astronomer Gennady Borisov. Following the appearance of the interstellar object 'Oumuamua in 2017, this was the second object from another solar system ever discovered wandering through our cosmic neighborhood. On Dec. 15 and 16 in 2019, astronomers took a closer look at 2I/Borisov using the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), a giant radio telescope in Chile Atacama Desert.

In the new study, an international team of researchers, led by planetary scientists Martin Cordiner and Stefanie Milam from NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, analyzed 2I/Borisov's chemical makeup.

Related: Interstellar comet: Here's why it's got scientists so pumped up

The researchers found that the gas coming from the comet contained more carbon monoxide (CO) than has been detected in any other comet this close to the sun (less than 186 million miles, or 300 million kilometers). In fact, the concentration of CO in the gas coming from this comet was between nine and 26 times higher than in the average comet in our solar system, according to a statement from the National Radio Astronomy Observatory (NRAO), which oversees ALMA.

Using ALMA, the team detected both CO and hydrogen cyanide (HCN). However, they found a similar amount of HCN in 2I/Borisov that's found in other comets in our solar system, so that discovery wasn't much of a surprise. But the unexpectedly high quantities of CO offered a major clue as to where this comet came from. "The comet must have formed from material very rich in CO ice, which is only present at the lowest temperatures found in space, below minus 420 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 250 degrees Celsius)," Milam said in the same statement.

"If the gases we observed reflect the composition of 2I/Borisov's birthplace, then it shows that it may have formed in a different way than our own solar system comets, in an extremely cold, outer region of a distant planetary system," Cordiner said in the same statement

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Astronomers do not yet know what kind of star 2I/Borisov formed around, but these researchers suspect that 2I/Borisov came from a cold region in a larger protoplanetary disk, or rotating disk of dust and gas around a young star from which planets and planetary objects form, Cordiner said. "Many of these disks extend well beyond the region where our own comets are believed to have formed, and contain large amounts of extremely cold gas and dust. It is possible that 2I/Borisov came from one of these larger disks," Cordiner said.

2I/Borisov was traveling pretty quickly (about 21 miles per second (33 km/s)) when it zoomed through our solar system. Researchers think that, whichever solar system it came from, it was likely torn from that system by the gravity of a passing star or large planet, according to the statement. After a long trip through space, it has made history as one of only two interstellar visitors ever identified in our solar system.

With this new study, not only are researchers discovering more about the possible origins of 2I/Borisov, they are also learning more about interstellar objects and other planetary systems in general. "2I/Borisov gave us the first glimpse into the chemistry that shaped another planetary system," Milam said.

Further studies and possible future observations of other interstellar comets will add to this understanding and also show whether 2I/Borisov and its unusual makeup is typical for such an object.

"Only when we can compare the object to other interstellar comets will we learn whether 2I/Borisov is a special case, or if every interstellar object has unusually high levels of CO," Milam said.

This study was published today (April 20) in the journal Nature Astronomy.

- We could chase down interstellar Comet Borisov by 2045

- 'Oumuamua: The solar system's 1st interstellar visitor explained in photos

- 1st color photo of interstellar comet reveals its fuzzy tail

Follow Chelsea Gohd on Twitter @chelsea_gohd. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save 45% on 'All About Space' 'How it Works' and 'All About History'!

For a limited time, you can take out a digital subscription to any of our best-selling science magazines for just $2.38 per month, or 45% off the standard price for the first three months.

Chelsea “Foxanne” Gohd joined Space.com in 2018 and is now a Senior Writer, writing about everything from climate change to planetary science and human spaceflight in both articles and on-camera in videos. With a degree in Public Health and biological sciences, Chelsea has written and worked for institutions including the American Museum of Natural History, Scientific American, Discover Magazine Blog, Astronomy Magazine and Live Science. When not writing, editing or filming something space-y, Chelsea "Foxanne" Gohd is writing music and performing as Foxanne, even launching a song to space in 2021 with Inspiration4. You can follow her on Twitter @chelsea_gohd and @foxannemusic.