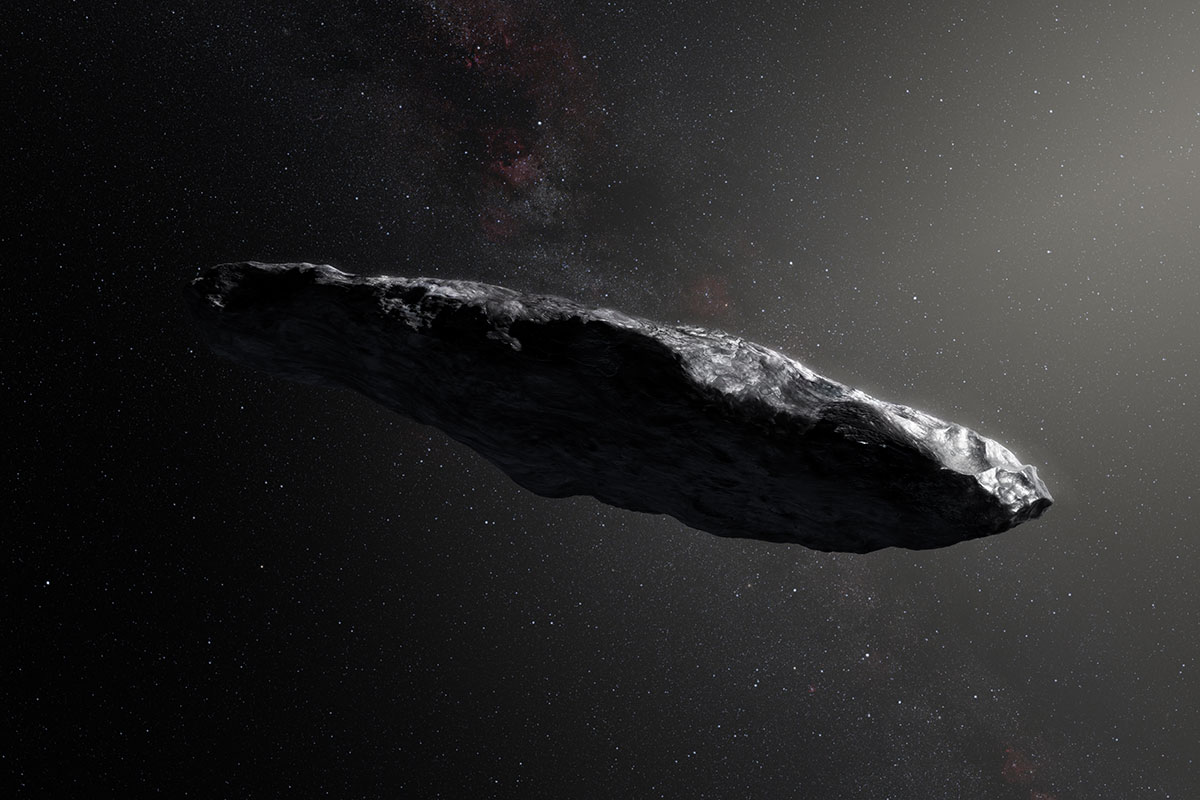

Life may have traveled to Earth from afar, aboard an interstellar visitor like the weird, cigar-shaped object 'Oumuamua, researchers say.

'Oumuamua, which zoomed through the inner solar system last fall, is the first confirmed interstellar object ever observed in our neck of the woods. But that doesn't mean it was the first ever to get here — far from it, in fact.

"We think that something like an 'Oumuamua ... there's always one within about 1 AU of the sun at any given time," planetary scientist Bill Bottke said last month during a panel discussion at the Breakthrough Discuss conference at the University of California, Berkeley. (One AU, or astronomical unit, is the average Earth-sun distance — about 93 million miles, or 150 million kilometers.)

Related: 'Oumuamua: Our 1st Interstellar Visitor Explained in Photos

"And that actually has some really interesting implications," added Bottke, who directs the Department of Space Studies at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado.

One such implication centers on the role that 'Oumuamua-like objects could play in the transfer of life from world to world around the cosmos, an idea known as panspermia.

'Oumuamua's exact size is unknown, but researchers think it spans less than 2,600 feet (800 meters) in its longest dimension. The object displayed "nongravitational acceleration" as it cruised away from the sun, spurring speculation that 'Oumuamua could be an alien spacecraft of some kind. But the consensus view is that the interloper is icy and its weird movements were caused by comet-like outgassing.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This tells us that ices can survive over these interstellar distances," astrobiologist Karen Meech, of the University of Hawaii's Institute for Astronomy, said during the Breakthrough Discuss panel.

Previous research on comets and other small bodies within our own solar system suggests that 'Oumuamua-like objects provide good thermal insulation and radiation shielding, she added. That's good news for any microbes that may be hitching a ride.

"You're probably getting significant protection on the inside, and you're not getting any deeper with the radiation field or heating from supernovae below 10, 20 meters [33 to 66 feet] depth in a body," Meech said. "So, the idea that you could bring some living organism in some state — it could be preserved in a cold deep freeze. So, it would be no different than coming from our outer solar system."

Astronomers have not yet identified 'Oumuamua's natal star system, so we don't know long ago the object was ejected into the dark and frigid wastes. But it may have been traveling through interstellar space for 10 million years or more, Meech said.

It's unclear if any putative critters aboard 'Oumuamua could have survived an impact with Earth. The icy object barreled past us at about 134,000 mph (215,000 km/h) relative to our planet, Meech said.

"That's a very high impact velocity," she said. (And it could have been even higher. 'Oumuamua came from above the plane of our solar system; an interstellar body hitting us more head-on could have an impact velocity of around 225,000 mph, or 360,000 km/h, Meech said.)

But 'Oumuamua and its kin are thought to be quite fluffy, so any that impact Earth are likely to "land" relatively gently and break open when they hit our atmosphere, Steinn Sigurdsson, a professor in the Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Penn State University, said during a different talk at the Breakthrough Discuss meeting.

Previous work by Harvard University astronomer Avi Loeb and others, along with Sigurdsson's own calculations, suggests that about 100 'Oumuamua-like objects have slammed into Earth over our planet's nearly 4.6-billion-year history, Sigurdsson said. (This is assuming these bodies are on random trajectories — that they weren't sent on their way by intelligent aliens, an idea known as directed panspermia.)

Related: 13 Ways to Hunt Intelligent Aliens

"Now, if any of them have biota in them? We don't know," he said. "Maybe we should go catch one and drill into it."

Catching 'Oumuamua is not feasible, said Loeb, who chairs Harvard's astronomy department and recently co-authored a paper speculating that 'Oumuamua might be an alien sailcraft. We don't know exactly where the object is now, so any chase probe would have to be equipped with a powerful (and heavy and expensive) telescope, he said. And gaining enough speed to catch up to 'Oumuamua would require slingshotting around the sun at a dangerously close distance.

"It makes much more sense to search for the next interstellar object," Loeb said during the question-and-answer portion of the Breakthrough Discuss panel. (He was in the audience, not on the dais.)

The powerful Large Synoptic Survey Telescope, which is scheduled to start observing the heavens from Chile next year, will probably spot about one interstellar object per month when it's fully up and running, Loeb added.

"So, just wait a few years and have one per month and just go after those with much less cost," he said. "If you detect them on their approach to us, you can actually meet them halfway at relatively low speeds."

It's also possible, of course, that life took a relatively short leap to Earth long ago. The terrestrial planets in our solar system swap rocks fairly regularly, as the ever-growing collection of Mars meteorites here on Earth attests. Indeed, some researchers think life probably started on the Red Planet and made its way to Earth aboard a rock lofted into space by a powerful impact.

All of this being said, panspermia — interstellar or local, directed or natural — is not the canonical explanation for life's emergence on Earth. There's no evidence for it, after all, so most researchers go with Occam's Razor and presume that we're native to our blue marble.

- 7 Theories on the Origin of Life

- If 'Oumuamua Is an Alien Spacecraft, It's Keeping Quiet So Far

- Interstellar Object 'Oumuamua's Surprise Arrival Still Thrills Scientists One Year Later

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.