Scientists Chat Interstellar Probe Project in New York City

An interstellar mission is "the next order of magnitude step" after Voyager, according to one astrophysicist.

NEW YORK — The Interstellar Probe, an ambitious concept to journey toward the edge of the solar system, is inching closer to becoming a reality. During a panel event held at The Explorers Club here on Oct. 17, scientists discussed the idea of sending a spacecraft 90 billion miles (145 billion kilometers) away from the sun.

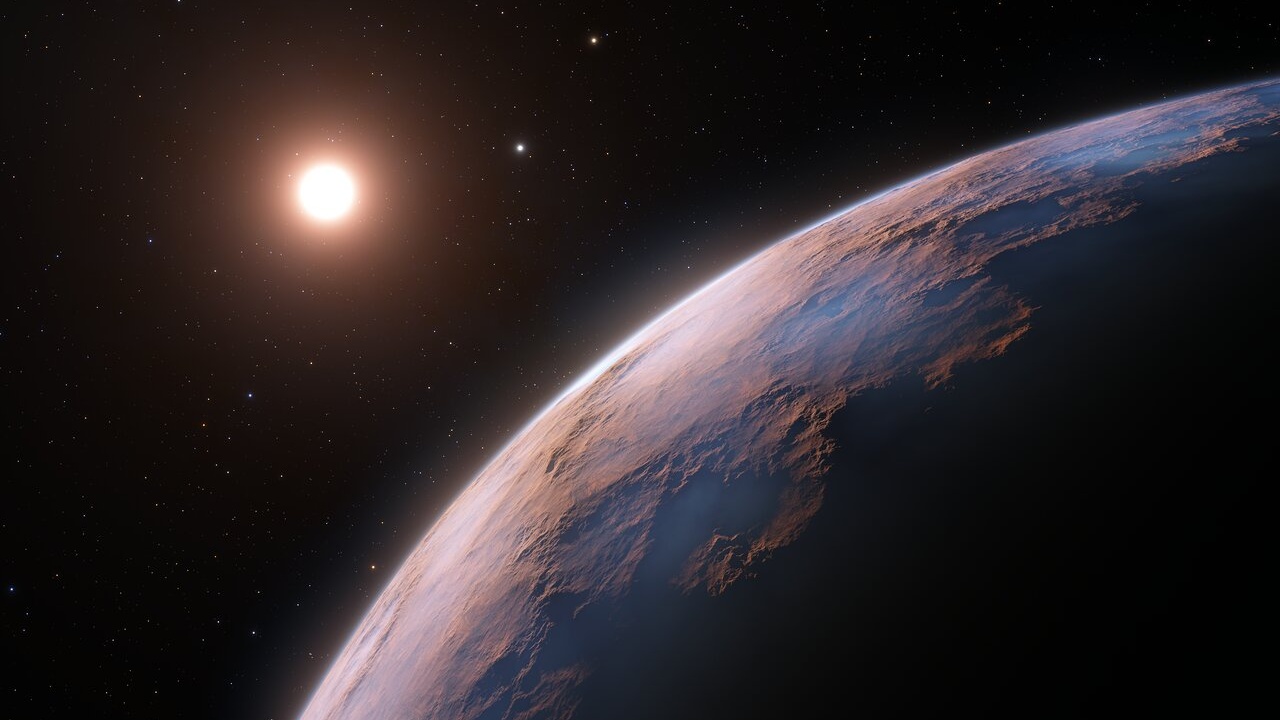

Earth and its sibling planets bob around our solar system like goldfish in a bowl, which, in this case, is a boundary produced by the sun. Now, imagine if a fish could send a probe outside the bowl to learn about its place in your living room. This funny thought is a bit like the idea behind the Interstellar Probe.

Sending scientific instruments to the edge of the heliosphere, or the sun's region of influence, is like going to the edge of a fish bowl. Getting outside the heliosphere and looking back at the solar system — beyond the bowl — could inform a whole new scientific perspective about our place in the cosmos.

Related: A Wild 'Interstellar Probe' Mission Idea Is Gaining Momentum

Space technology has evolved to enable new science missions. Groundbreaking investigations have been supported by tech ranging from orbiting space telescopes to the cameras onboard up-close-and-personal missions like Cassini, Juno and New Horizons, which have taken incredibly sharp images of Saturn, Jupiter and Pluto, respectively.

"What we've never done is take a spacecraft and put it outside of our entire solar system," Jason Kalirai, an astrophysicist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab in Maryland, said during the panel.

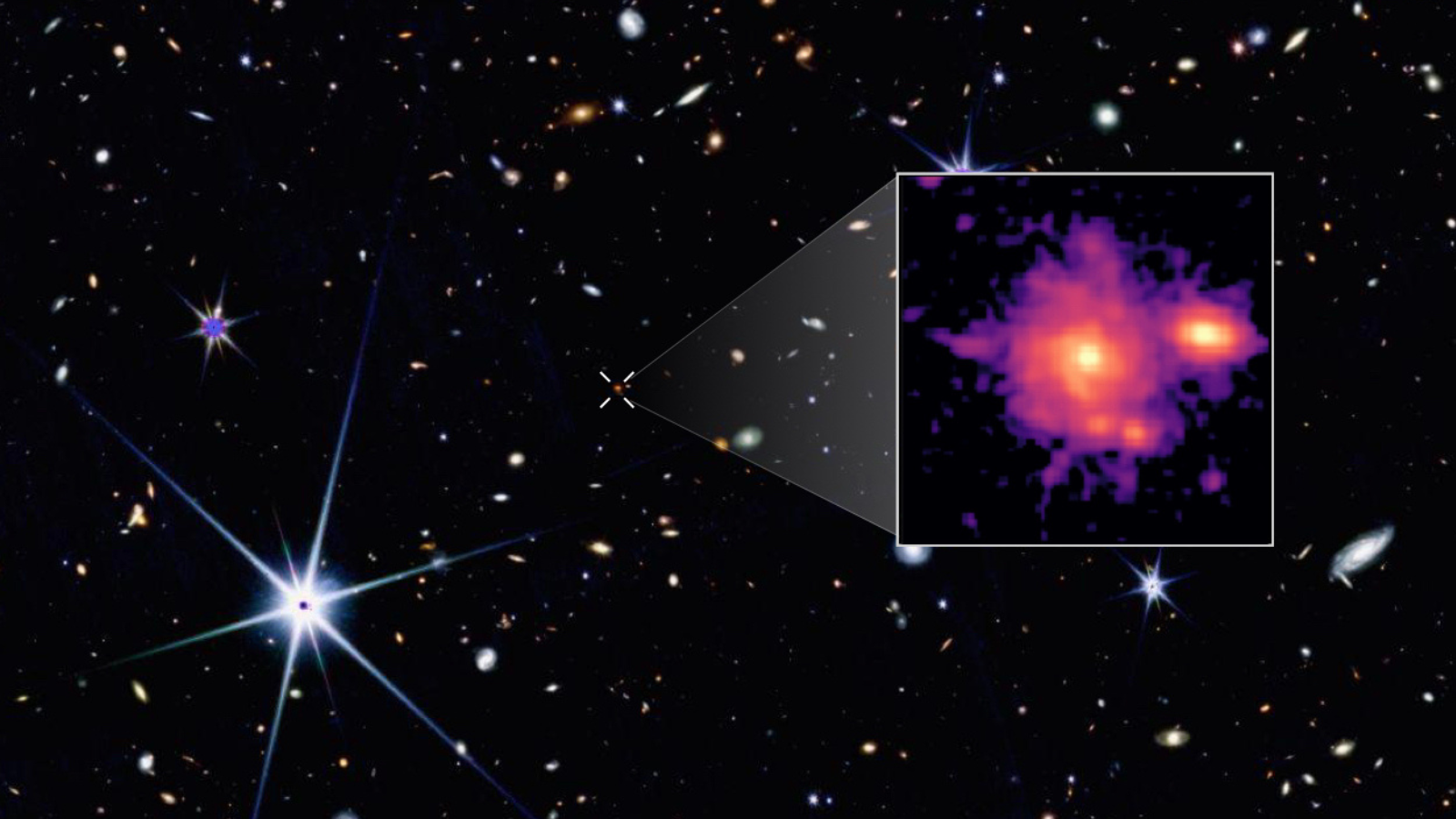

The sun influences a region around itself where Earth, comets and other planets move about. This "bubble" acts like a barrier to keep out dangerous cosmic radiation and keep in the charged particles released by the sun, which are essential for plants and humans. By sending a probe into interstellar space, scientists could better understand how this bubble formed and what the bubbles surrounding other stars might be like.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The kinds of questions that we can ask about the heliosphere while we are still inside of it are subject to a number of different biases, according to Princeton University heliophysicist Jamey Szalay, who was also part of the panel. As he put it, an interstellar mission is "the next order of magnitude step" after Voyager.

NASA's Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, which launched in 1977, became the first probes to exit the solar system. In August 2012, Voyager 1 reached interstellar space as it observed that it was surrounded by a 9% increase in galactic cosmic rays coming from outside the solar system. Voyager 2 entered interstellar space six years later, in November 2018. The incredible duo continues to send back data to Earth, and is a testament to multigenerational scientific exploration.

While it is still in its early stages, NASA hopes that its Space Launch System (SLS) rocket will take the Interstellar Probe to the edge of our "fishbowl" in less time than Voyager 1's 35-year journey. According to a panel comment from Rob Stough, the utilization manager for the SLS, the rocket's next-generation heavy-lift launch capability could support the Interstellar Probe and its potential legacy.

Researchers are still deciding which spot on the heliosphere fish bowl to aim the probe toward. "We're not exactly sure which direction [to take] out into the interstellar medium," Michael Paul, Interstellar Probe Study Lead at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Lab, told Space.com before the panel discussion. "Do we go in a direction that follows the Voyagers, do we go in a direction that is indicated by new science that [will] come in from missions like IMAP, that IBEX has shown us, [or] do we take a new direction altogether?"

"We don't know which direction we're going to leave in yet … [and] we are open-minded about where we are going to visit on the way out," Paul added.

There's still plenty to sort out, but enthusiasm is already in place and growing for the Interstellar Probe.

- Hubble Space Telescope Spots Interstellar Comet Borisov (Video)

- Is Interstellar Travel Really Possible?

- Chuck Berry's Music Is Traveling Through Interstellar Space

Follow Doris Elin Urrutia on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.