These Scientists Want to Send a NASA Probe to Jupiter's Volcanic Moon Io

When it comes to moons of the outer solar system, potentially habitable worlds tend to steal the spotlight — but if a team of scientists get their way, NASA may send a mission to a world that's certainly dead biologically, but far from it geologically.

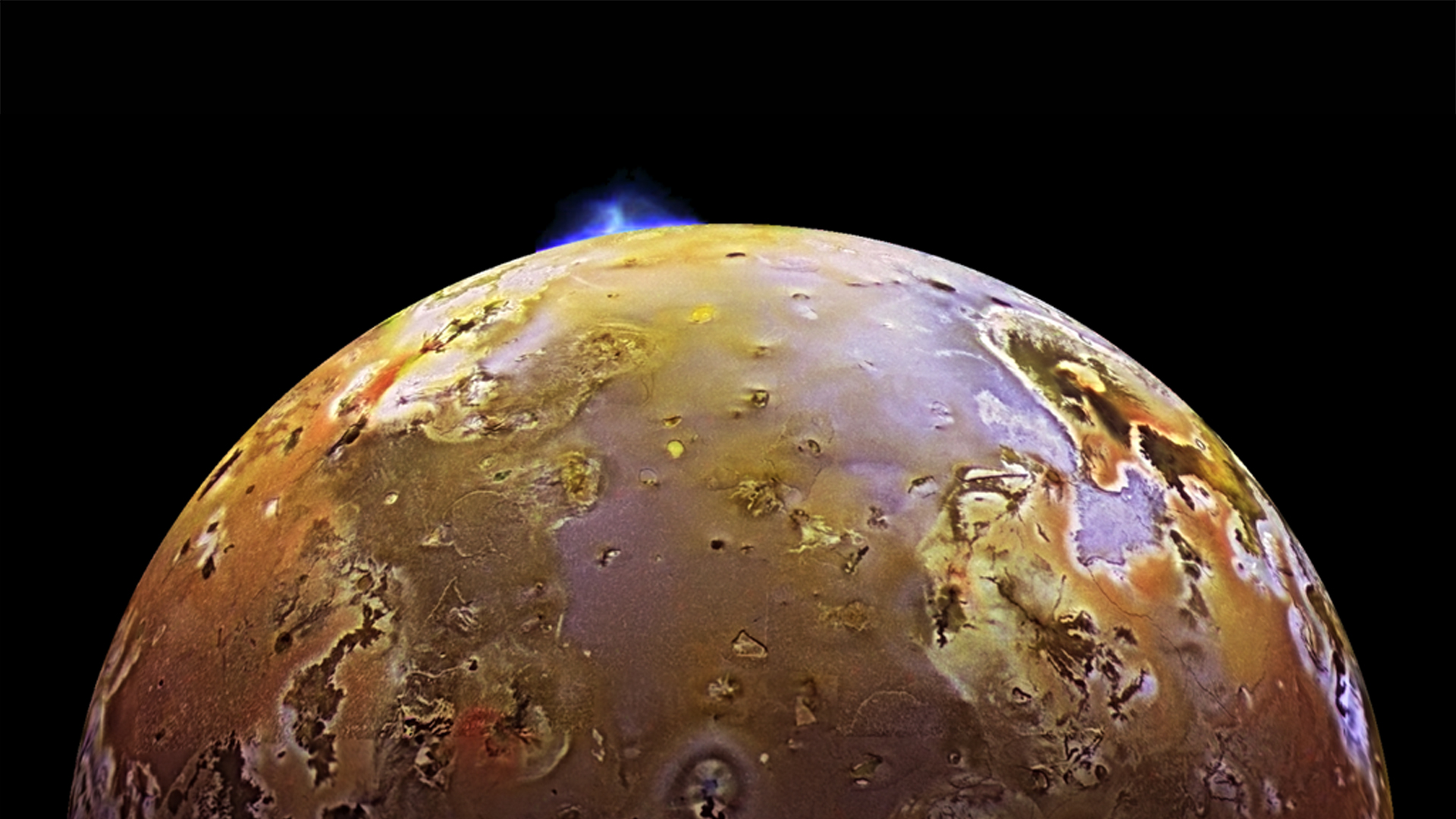

That world, Jupiter's incredibly volcanic moon Io, is the target of a mission that scientists are proposing to NASA for the third time, after a refocusing that they hope will make the project more appealing to the space agency. Known as the Io Volcano Observer (IVO), the mission would launch in 2026 and arrive at its target in 2031. There, it would, as the mission's new motto goes, "follow the heat" in order to understand how the gravitational tugs that the moon experiences trigger its extreme volcanic eruptions.

"Tidal heating is a process that is happening throughout the cosmos," Alfred McEwen, a planetary geologist at the University of Arizona and the principal investigator on the IVO mission, told Space.com. On icy moons like Jupiter's Europa and Saturn's Enceladus, tidal heating melts their interiors to form the massive oceans that scientists believe or know to be hiding under the surface, and the same phenomenon is also believed to play out in other solar systems. But on Io, it's truly a force to be reckoned with. "Io is the best place to study it because it is so pronounced there," McEwen said.

Related: Amazing Photos: Jupiter's Volcanic Moon Io

No space agency has ever sent a dedicated mission to Io; most of what scientists know about the moon today comes from the Voyager mission through the outer solar system, the Galileo mission to Jupiter and ground-based observations. Before Voyager flew by, scientists didn't even realize the moon hosted active volcanic eruptions, which are now its most famous characteristic.

But for now, the only new data scientists can gather about the moon comes from the ground, and telescopes can't get a detailed look at Io's dramatic surface activity. "I would love to see another mission to Io," Julie Rathbun, a planetary scientist at the Planetary Science Institute who studies Io's volcanism but who isn't involved in the IVO proposal, told Space.com. "Getting a mission to Io is just really hard."

The proposed IVO mission would fit NASA's Discovery program, the same budgetary class that has included the Kepler planet-hunting telescope, the InSight lander that has just begun its work on Mars and the Dawn mission to the asteroid belt. In part, that relatively low price is enabled by reusing instruments designed for other spacecraft, including for the upcoming Europa Clipper and European Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer missions, as well as for the European-Japanese BepiColombo mission currently en route to Mercury.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The mission's flight design helps make the spacecraft's radiation exposure more manageable. "We make close flybys, but they're very fast and furious because the radiation is intense, so we get out," McEwen said. The IVO probe would make 10 such flybys over the course of four years, each carefully timed to the signals of tidal heating, which powers the volcanoes.

Tidal heating is the result of the gravitational interaction of different planetary bodies. In Io's case, its gravity interacts with those of its giant neighbor Jupiter, plus its companion moons, Europa and Ganymede. Those interactions are particularly strong because the moons' orbits are synched up: for every once Ganymede orbits, Europa orbits twice and Io orbits four times.

That clockwork relationship, which scientists call Laplace resonance, means Io experiences particularly severe tidal heating. But scientists don't know precisely what's inside Io — whether its heart is molten rock or solid — which makes it difficult to know how that tidal heating is actually working.

Related: Orbits of Jupiter Moons Transformed into Mind-Bending Optical Illusions and Music

IVO would solve that. Its instruments will be able to determine whether Io hides a global magma ocean or whether its volcanoes rise from mostly solid rock. They will also be able to measure the composition and temperature of lava on the moon's surface, which scientists can use to determine how violent and how frequent the eruptions are.

The implications wouldn't be limited to a distant moon but to all worlds that experience tidal heating. And IVO may teach us about our own world as well.

Life on Earth has weathered five major mass extinctions, and each extinction corresponds with upticks in dramatic volcanic activity, McEwen said. Io may be the closest model to eruptions that cataclysmic, pouring out that much lava and volcanic gas. "Io provides very large-scale lava eruptions, very high temperatures, of a sort that was common in the early histories of the terrestrial planets," McEwen said. "If you want to understand it, it's really better to see it happen, and Io's the only place to go to do that."

Volcanic eruptions on Earth are notoriously complicated; it's why scientists can't predict eruptions despite their best monitoring. But at Io, not only are eruptions simple, they are also prevalent.

"It's like this gift — if you really want to understand volcanism, here's where you go," Rathbun said. "Io is almost volcanoes in their pure form."

- Lava Waves Sweep Across Jupiter Moon Io's Massive Molten Lake

- Was Ancient Earth Like Jupiter's Super-Volcanic Moon Io?

- Jupiter and Two of Its Biggest Moons Loom in Stunning Juno Photo

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.