Scientists Present Best Images Yet of Ionosphere From Space

Fresh findings about the edge of Earth's atmosphere are puzzling scientists affiliated with two missions that launched this year, and then some.

This zone, at an altitude of roughly 50 to 400 miles (80 to 645 kilometers), is full of strange physical phenomena that scientists are only beginning to understand. In the ionosphere, charged particles released by the sun interact with gases at the top of Earth's atmosphere in intriguing ways.

Take, for example, the "aurora seashell." During a NASA internship, Jennifer Briggs spotted images of an Arctic aurora, or northern lights, that had a strange spiral. This whirlpool suggested a large disturbance in the magnetosphere, which is the zone bordering the ionosphere. Weirder still, the sun did not release any eruptions before the disturbance.

Related: Amazing Auroras: Breathtaking Northern Lights Photos

Briggs, an undergraduate physics student at Pepperdine University in California who was in search of the cause of the formation, scoured data from multiple sources: all-sky cameras, radars and NASA's Magnetospheric Multiscale mission that studies this part of the atmosphere. And the result was surprising, according to a NASA statement.

Briggs and her colleagues found that a region called the foreshock seemed to cause the aurora seashell, rather than an outburst from the sun, according to a NASA statement. The foreshock occurs where energetic particles from the sun bounce off Earth's magnetic field.

NASA has more data about the ionosphere than ever before; the agency has launched two new missions targeting the region within the past year.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

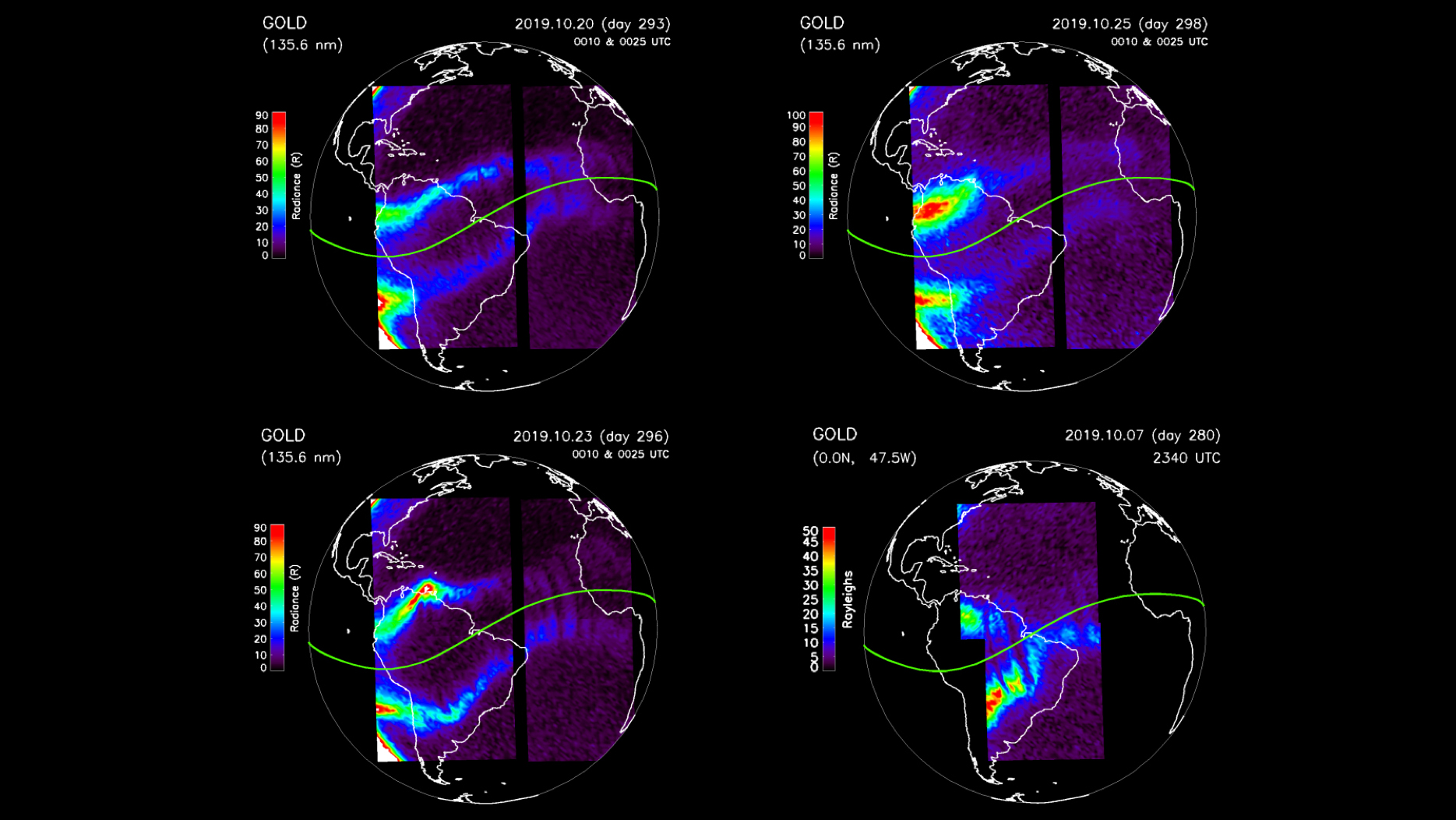

The agency's Global-scale Observations of the Limb and Disk (GOLD) satellite launched in January to geostationary orbit, roughly 22,000 miles (35,000 km) above Earth. (For comparison, the International Space Station orbits about 250 miles, or 400 km up).

GOLD has made several discoveries in the past year. For one, it showed scientists that when a solar storm hits Earth, atomic oxygen becomes more common at low latitudes and rarer at high latitudes. At the same time, molecular nitrogen prevalence does the opposite, decreasing at low latitudes and increasing at high latitudes.

The spacecraft also showed what happens to the ionosphere during nights and solar eclipses, when the sun's energy is not striking a particular region of Earth. Here, the atmosphere cools down, the ionosphere thins and charged particles eventually clump into crests around the Earth's magnetic equator.

Stranger still, this clumping process varies from night to night, for reasons that are still unclear. "These were very surprising findings to me, and to the rest of the team who's been looking at this stuff for many years," GOLD principal investigator Richard Eastes, a research scientist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said in the same statement. "It's not something we anticipated at all."

A second NASA mission targeting the ionosphere dubbed the Ionospheric Connection Explorer (ICON) launched on Oct. 10 and began science observations on Dec. 1.

At the same news conference where Briggs and Eastes discussed their work on the ionosphere, the ICON principal investigator, Thomas Immet of the University of California Berkeley, showed off some of the earlier data from the mission, gathered while engineers with commissioning and calibrating the spacecraft.

All told, ICON carries three different imagers to study the way the different gases that make up Earth's atmosphere glow in the light of our sun. So far, those instruments have returned exactly the sort of information scientists expected, Immel added, but that's what's supposed to happen during commissioning.

"The first thing we see is a bit boring, but I'm excited nevertheless," he said in the same statement. "It's exactly what you would expect if the instrument were working perfectly."

The three scientists presented their findings on Dec. 10 at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

- ICON: NASA's Ionospheric Connection Explorer Satellite Mission in Pictures

- Earth's Colorful Atmospheric Layers Photographed from Space

- NASA Rockets Launch to Unveil Mysteries of the Northern Lights

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.