Ireland's lost Apollo 11 moon rock traced from basement to fire in documents

Recently released documents reveal how Ireland struggled to find homes for two moon rock displays gifted by the U.S.

New details about the small pieces of the moon gifted by the United States to Ireland in 1970 have now been unearthed. Unfortunately, the same cannot be said for the Apollo 11 lunar samples, themselves.

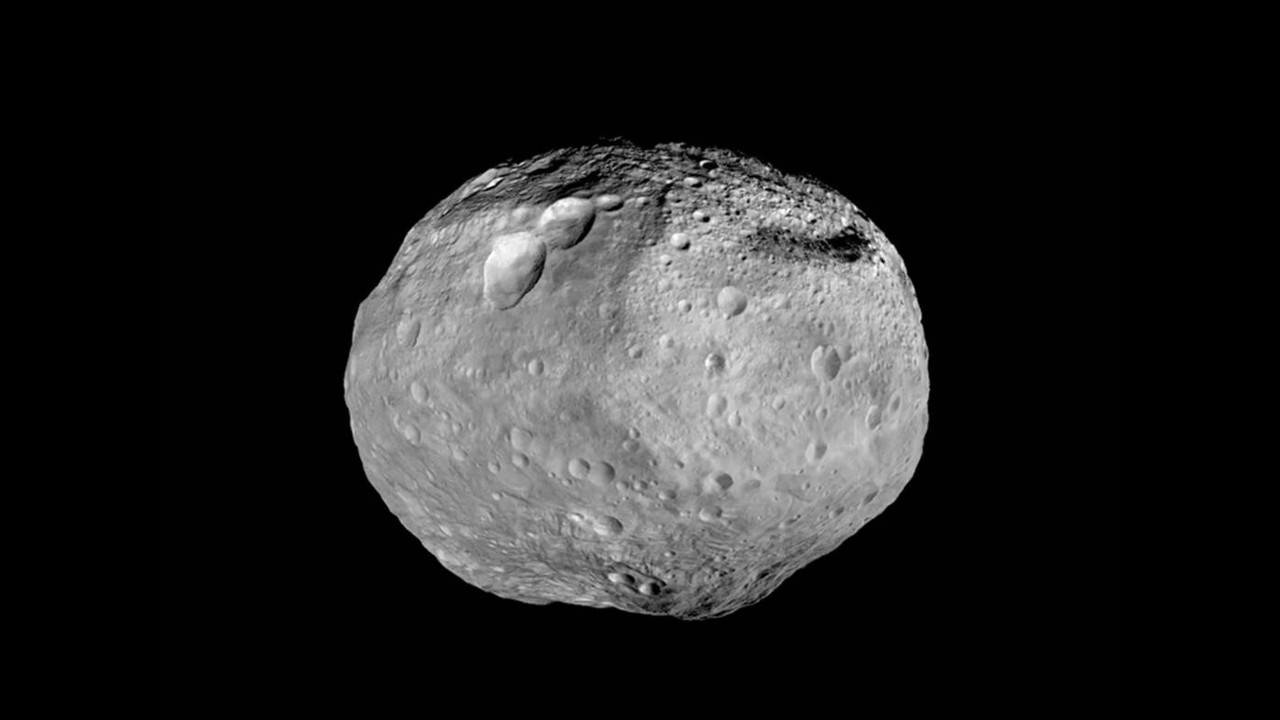

The four moon pebbles, which were embedded in a single lucite ball and mounted to a wooden podium together with a small flag of Ireland that was flown on NASA's first lunar landing, was one of 135 such goodwill presentations that the U.S. made to foreign countries following the Apollo 11 mission in 1969. Additional displays were prepared for the United Nations, Vatican City, the 50 U.S. states and the U.S. territories.

Although many of those displays have gone missing in the intervening years, the fate of Ireland's Apollo 11 display has been known for decades. Tragically, it was caught up in an Oct. 3, 1977 fire that tore through Dunsink Observatory in Dublin, where the 0.002 ounces (0.05 grams) of Apollo 11 moon dust was on display.

By all accounts, whatever little remained after the fire was hauled off to a landfill in nearby Finglas, where it remains buried to this day.

Recently-released "confidential" documents from the National Archives of Ireland do not dispute or add additional detail to the outcome, but rather shed light on how the lunar display came to be at the observatory.

"This piece was given on Sept. 4 1973, on the advice of the Department of Education, to the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies for display at the Dunsink Observatory," reads a 1984 memo, as cited by PA Media, a UK-based multimedia news agency that distributed the news about the documents. "This piece of moon rock had lain in the basement of this department for three-and-a-half years due to indecision as to where it might best be displayed."

Originally presented to Ireland's then-President Eamon de Valera by American ambassador J.G. Moore in 1970, the Apollo 11 goodwill moon rock laid in limbo until 1973, when it was learned that the U.S. intended to gift the country with a second lunar sample, this one from Apollo 17, the sixth and last lunar landing in December 1972.

"It was thought that some embarrassment would be caused if the first piece was not already on display," the memo's authors wrote, explaining why the Apollo 11 gift was sent to Dunsink.

As for Ireland's piece of the Apollo 17 goodwill moon rock, it was initially placed on display in the drawing room of Aras an Uachtarain, the official residence and principal workplace of the president. Later, it was loaned to Aer Lingus so it could be featured in the airline's young scientist exhibition of 1976.

The Apollo 17 sample, which unlike the Apollo 11 display exhibited a 0.04-ounce (1.142-gram) stone that had been cut from a single rock and then mounted to a wooden plaque, was briefly planned to return to Aras an Uachtarain for permanent display but was ruled out given that the residence was only open to invited guests.

"The most appropriate museum collection in which it might be exhibited would be the geological or mineralogical collection — [but] the [National] Museum has no space to mount its geological exhibition and therefore the moon rock would have to be put into storage, which would not satisfy the requirements," read one of the documents.

Instead it was decided to transfer the Apollo 17 display to Aer Rianta, operator of the nation's major airports, for its public exhibition beginning in October 1975. That was only temporary, though, as eight years later the moon rock was returned to the government for display by the Geological Survey Office.

Today, Ireland's Apollo 17 goodwill moon rock display is on exhibit at the National Museum of Ireland, alongside a collection of meteorites, as well as plates from an Irish cosmic ray experiment that was carried to the moon on Apollo 16 and 17.

Ireland's Apollo 11 lunar sample was not the only display to be lost in a fire. A similar moon rock-topped podium presented to the people of Alaska was thought claimed by a 1973 fire in Anchorage until a ship's captain from a reality TV show revealed he was in possession of it 40 years later. Federal authorities intervened and the Apollo 11 sample was returned to display at the Alaska State Museum in Juneau in 2012.

The Apollo 11 and Apollo 17 lunar sample displays were the only pieces (an Apollo 12 moon rock display was gifted to China, the only known exception) of Apollo-collected moon rock to be released from U.S. property. The remainder of the 842 pounds (382 kg) of lunar material brought to Earth by the six NASA missions is considered a natural treasure, with samples being made available through loans for scientific study, museum display and educational outreach.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on X at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2024 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.