An Israeli moon lander just took to the skies, but we'll all have to wait nearly two months for its historic touchdown try.

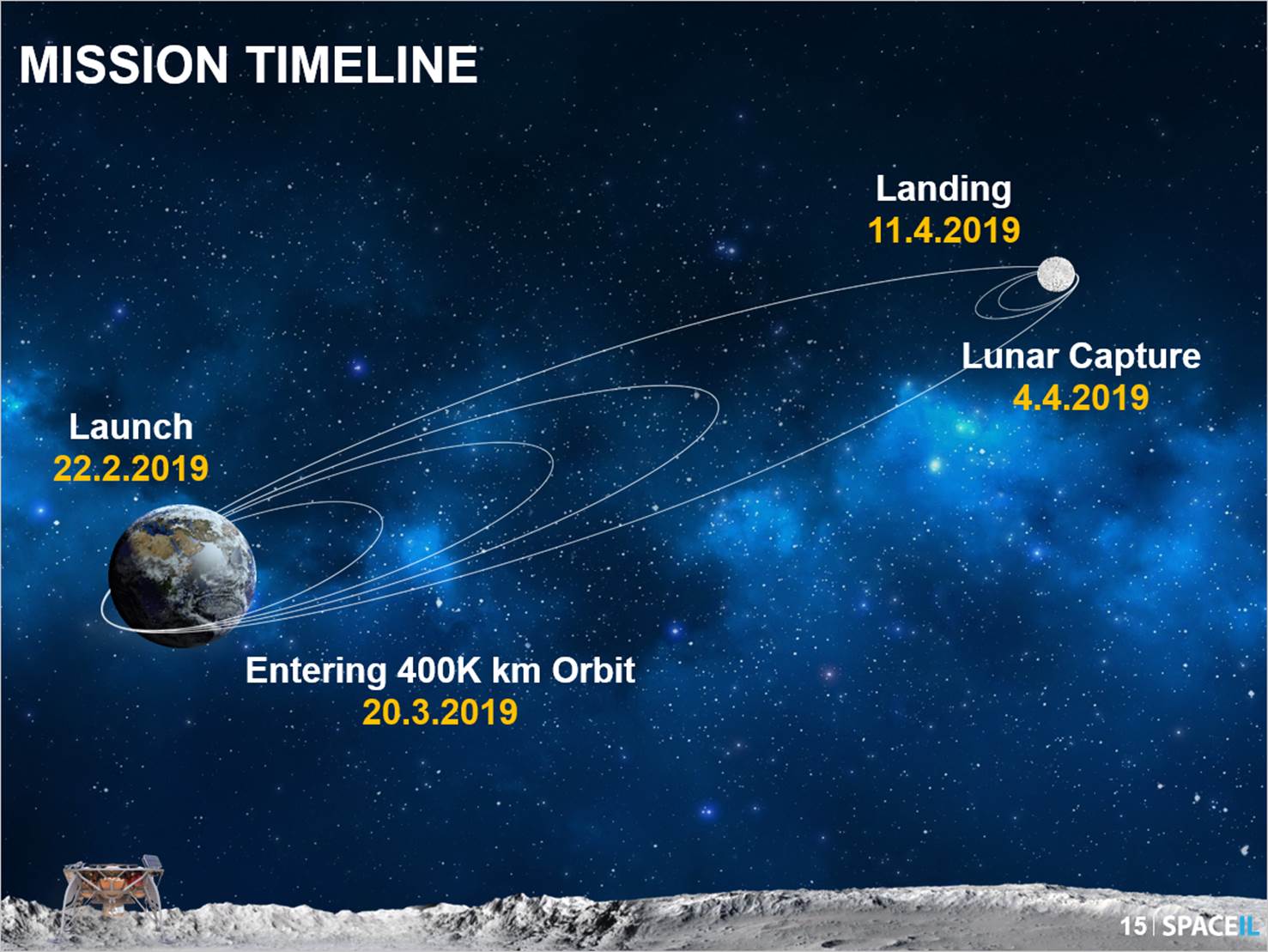

The robotic lander, called Beresheet, launched atop a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket yesterday evening (Feb. 21) from Florida's Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. If everything goes according to plan, Beresheet will zip around Earth for about six weeks in ever-widening orbits before heading toward its final destination. The craft will arrive in lunar orbit in early April and attempt a landing on the 11th of that month.

Beresheet will end up putting about 4 million miles (6.5 million kilometers) on its odometer when all is said and done. That's more than any other moon-landing mission, said the spacecraft's builders, the nonprofit group SpaceIL and the company Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI).

Related: Israel's 1st Moon Lander Beresheet in Pictures

Beresheet's lengthy stay in Earth orbit may seem surprising. After all, China's Chang'e 4 farside lander reached lunar orbit just 4.5 days after its Dec. 7 liftoff (though Chang'e 4 didn't actually touch down until Jan. 2).

But the 5-foot-tall (1.5 meters) Beresheet cannot take a direct path to the moon, project team members said, because the lander shared a rocket ride with two other payloads. Also aboard the Falcon 9 last night were an Indonesian communications satellite and an experimental U.S. Air Force craft, both of which are making Earth orbit their home.

"This is Uber-style space exploration," SpaceIL co-founder Yonatan Winetraub said Wednesday (Feb. 20) during a prelaunch news conference.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The strategy is cost-effective, helping keep Beresheet's total price tag, including launch, at about $100 million — quite low for a mission to another world. But there is a trade-off.

"The problem with that is, it doesn't allow us to choose the orbit completely," Winetraub added. "We have to consider the requirements from the other payloads" on the rocket.

And you can't just jet straight off to the moon from Earth orbit, Winetraub said; the two celestial bodies must be lined up properly before Beresheet — whose name means "in the beginning" in Hebrew" — can make its move.

"The moon is coming around, and we're doing our own orbit, and we need to synchronize everything," Winetraub said. "For that, we need to do something that's called 'phasing loops,' to make sure that the moon comes around in the right position so you can capture with it. And that takes time."

Mission team members won't just be sitting on their hands while they're waiting for this sync-up. The time in Earth orbit will allow them to test Beresheet's various systems and make sure they can track and communicate with the spacecraft. [The 21 Most Marvelous Moon Missions]

"Only after we will be sure that everything is OK, we will jump — make the lunar-capture maneuver, what we call it — and jump to the moon," Yigal Harel, the head of SpaceIL's spacecraft program, said during Wednesday's news conference.

The touchdown process will be fully automated and take about 20 minutes, team members said. Beresheet will land on the moon's near side, within the large basaltic plain called Mare Serenitatis ("Sea of Serenity").

A successful touchdown would be a huge deal. Beresheet would become the first privately funded craft to land on the moon. And the SpaceIL/IAI team would be the first nonsuperpower entity to pull off the feat: To date, only the Soviet Union, the United States and China have done it.

Beresheet will study the local magnetic field during its lunar approach and its two-Earth-day mission on the moon's surface. It will also investigate lunar craters, project team members have said. But the main mission goal is to inspire young people, especially kids in Israel, to become more interested in science, technology, engineering and math.

Indeed, team members have already met with many kids around the world, to bring the mission — and spaceflight in general — down to Earth.

"It is rocket science, but our goal is to show them that it's not magic — it's something they can understand," SpaceIL co-founder Kfir Damari said during Wednesday's briefing. "If they can understand that, and if they can meet engineers and hear their story and see that they come from all different kinds of backgrounds, they can understand that they themselves can be those who will build the next spacecraft."

Beresheet is toting an Israeli flag and a time capsule. Among the capsule's contents is the "Lunar Library," a collection of materials that includes the full English-language version of Wikipedia. The library is a project of the Arch Mission Foundation, which aims to help preserve human knowledge and culture by storing bits and pieces of it in off-Earth locales.

Beresheet began life as a moon-race robot. SpaceIL is a former competitor in the Google Lunar X Prize, a $30 million contest to put a robot on the moon and have it perform a few basic tasks. The Prize ended in 2018 without a winner, but SpaceIL — and several other former teams, including the American company Moon Express — have kept developing their moon missions.

Mike Wall's book about the search for alien life, "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate) is out now. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.