Astronauts on ISS can face muscle loss in microgravity — a new ESA experiment may help

The method works on Earth, could it work in space too?

On Aug. 27, Danish astronaut Andreas Mogensen scripted history when he became the first European to pilot the SpaceX Dragon spacecraft to the International Space Station (ISS).

Over the next six months, Mogensen will carry out over 30 research activities including 3-D printing in space, supporting astronauts' mental health with soothing virtual reality videos and clicking pictures of thunder clouds on Earth to better understand the phenomena. One experiment, however, is captivating scientists because of its potential to provide better healthcare not just for astronauts but also for humans on Earth.

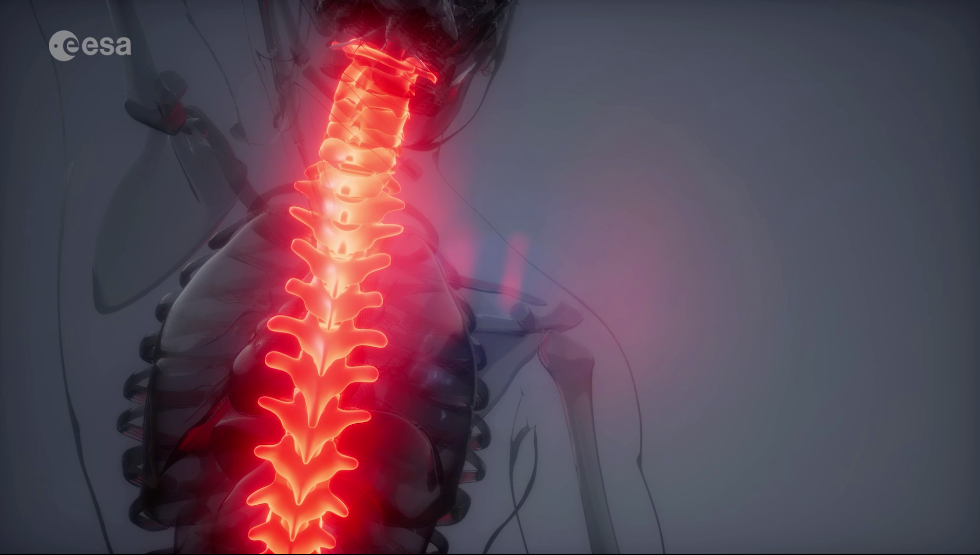

The device seeks to combat muscle loss in astronauts, which is an unavoidable medical consequence of long-term space missions. Past research has shown that a 30- to 50-year-old astronaut who spends six months in space loses half their strength, which means they basically return home with the muscles of an 80-year-old. The new experiment hopes to reduce these effects by electrically stimulating certain muscles such that they regain mass and, in turn, strength. Ultimately, this stimulation is expected to accelerate recovery.

Related: SpaceX Crew-7 astronauts will handle over 200 science experiments on ISS

With interest in long duration space missions to the moon and even Mars ballooning across the world, this method could be useful in counteracting the effects of microgravity on human explorers and in keeping them healthy, scientists say.

The method, called Neuromuscular Electrical Stimulation (NMES), is not new. On Earth, it is actually a well-known rehabilitation strategy for patients who experience prolonged periods of physical inactivity, such as those diagnosed with spinal cord injuries or cerebral palsy. Brief electrical pulses on target muscles result in relatively strong contractions, eventually offsetting the effects of extended disuse.

In space, however, the method has not been tested yet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Mogensen, who is an astronaut with the European Space Agency (ESA), is the first subject of this experiment. Mogensen belongs to what is called a control group, which means he represents a regular astronaut who may use the treatment in the future but he will not be subjected to the electrical stimulation itself.

Instead, he will perform measurements to assess his muscle health before and after his six-month flight to provide baseline statistics for future astronauts who will take the NMES treatment during space missions. That second group of astronauts will take the same muscle health measurements as Mogensen after undergoing the electrical stimulation. The results from both groups will then be compared to judge whether the treatment improved muscle health in the second group, researchers say.

More subjects for this experiment are yet to be decided, ESA told Space.com in an email.

This new method is expected to complement and not replace the current exercise regime followed by astronauts during their space missions. On the ISS, the crew exercises for at least two hours every day, which is a crucial countermeasure for weakening muscles.

These exercises are specific to the space agencies sending the astronauts and are also tailored to the individual. For example, astronauts from the United States, Japan, China and Canada go through resistance and aerobic training, while Russian astronauts prefer to use treadmills and exercise bikes among other equipment, according to a 2019 study.

However, the extent to which these countermeasures work vary across astronauts. As one example, a study that monitored two astronauts across six months of spaceflight showed that despite high intensity training — the astronauts ran for 500 kilometers (311 miles) with restraints close to their respective body weights — the crew still experienced muscle loss. Thus, the NMES method, which requires fewer resources than a mini-gym in space, could be an accessible and useful system that complements daily exercises, researchers say.

Although this method does not have any long-term safety concerns reported so far, it does have a few limitations. Sometimes it may not activate the entire muscle, according to the same 2019 study. Also, the effects of electrical stimulations on a few organs that deteriorate in space, such as those associated with the skeletal and cardiovascular systems, are not yet very well understood.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social