Exoplanets, dark matter and more: Big discoveries coming from James Webb Space Telescope, astronomers say

'We're going to be observing everything in our solar system that JWST can point to.'

The James Webb Space Telescope has dazzled us plenty already, but the best is yet to come from the observatory, mission team members say.

"We have a lot of fantastic work that's coming out from the telescope," Stefanie Milam, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) deputy project scientist for planetary science, told the audience Tuesday (March 14) at the South by Southwest (SXSW) Conference and Festivals in Austin, Texas.

"The science community is really working hard on analyzing their own data and putting it into scientific peer-reviewed publications, and that is now finally coming to fruition," added Milam, of the Astrochemistry Lab at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

Related: 12 amazing James Webb Space Telescope discoveries

A sensational, newly released JWST image of WR 124, a huge, exotic star that has already shed about 10 times the mass of the sun, is one example. The splendor of the image — taken last summer, just after JWST began its science operations — is illustrative of how the telescope's near- and mid-infrared instruments, in combination with the superior optics of its 21.3-foot-wide (6.5 meters) mirror, are able to show astronomers details they have never seen before.

In the case of WR 124, the data from the Near-Infrared Camera (NIRCam) and the Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI) reveal the clumpy structure of the dust surrounding WR 124, allowing astronomers to better understand how the dust is produced, the size and quantity of dust particles present, and how dust from other such "Wolf-Rayet" stars contributes to the Milky Way's overall dust content, which is then recycled in the next generation of stars and planets.

"One area where we're really getting a lot of new information is the birth of stars," Milam said at the SXSW event. "[We're] understanding star formation in a way that we've never really had access to, with this whole new sensitivity and detail that we've never had before. Not only are we seeing star formation in our own galaxy, but even in other galaxies … and we're getting this detail now that we used to only have for our own galactic understanding, now expanding into these other galaxies across the universe. It's just really an exciting time to be part of that field and understand how our sun was born and how the solar system was formed, and this is giving us that first real glimpse of it."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By peering through the clouds of dusty gas that envelop star-forming regions that are opaque at visible wavelengths of light, JWST's infrared vision is able to tease out these important details. But astronomers don't just want to learn about how stars and planets form; they also want to learn more about how they evolve. That's where the WR 124 observations come in — the central star shedding the nebula from its outer layers has a mass 30 times that of our sun and will eventually explode as a supernova. JWST is also promising to do the same for planets.

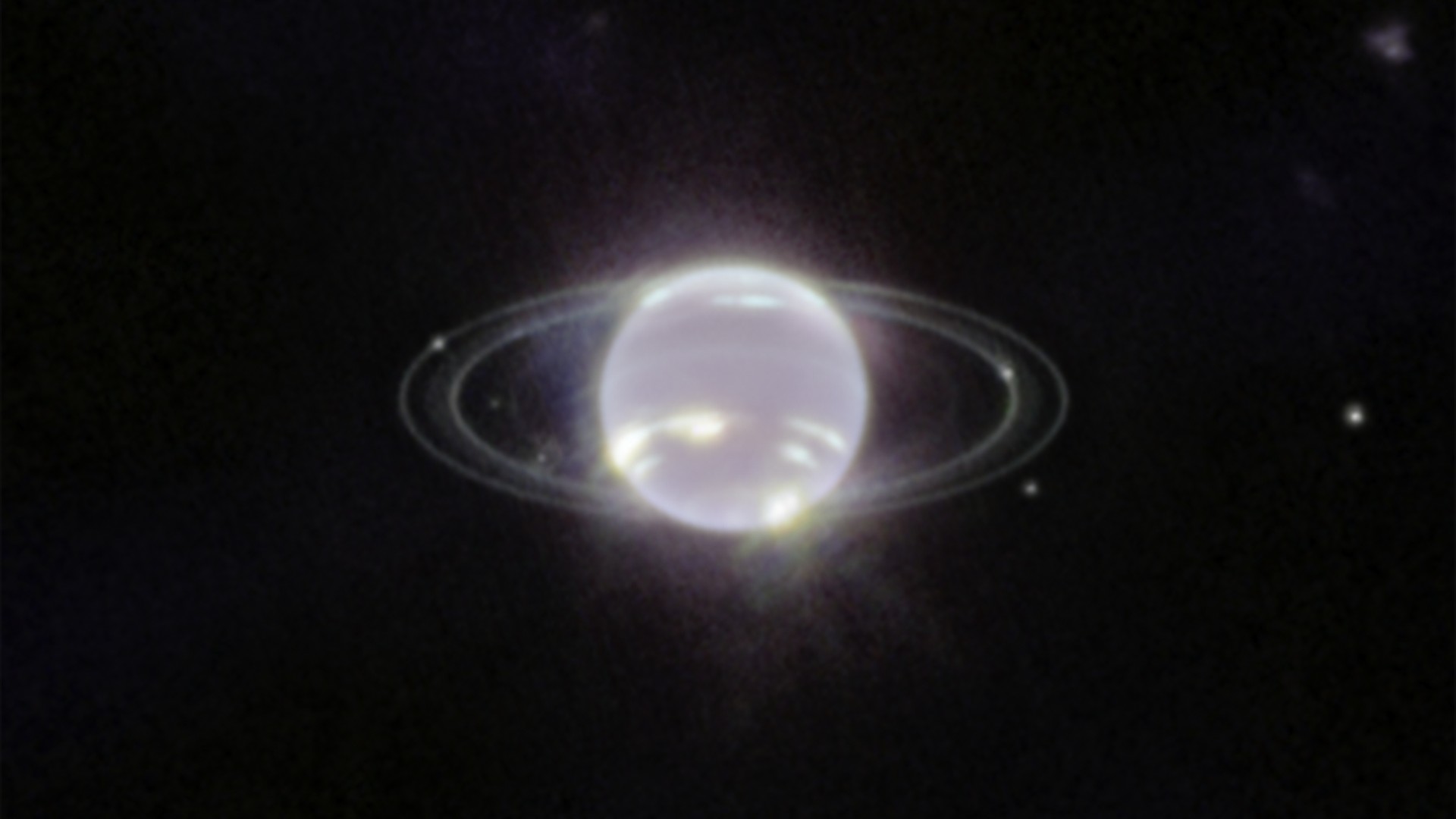

The planets of our solar system are one starting point. "We will be observing the solar system with the James Webb Space Telescope, and have been doing so," said Milam. Superb images of Mars, Jupiter and Neptune have already been released by the JWST team, as well as observations of the DART impact on the asteroid Dimorphos in September 2022.

"We're going to be observing everything in our solar system that JWST can point to, from near-Earth asteroids, comets, interstellar objects, all of the planets and their satellites to the farthest reaches of our solar system, including our favorite minor planet, Pluto," said Milam. "So, there's lots more to come."

Related: Solar system planets, order and formation: A guide

Beyond our solar system are more planets orbiting other stars. More than 5,000 exoplanets have been discovered to date, ranging in size from massive giants larger than Jupiter to small worlds the size of Mars. However, the easiest exoplanets to study have been the hot Jupiters — gas giants orbiting very close to their host star, at orbital radii of just a few million miles — because they produce the strongest signal.

JWST's earliest exoplanet results have also come from hot Jupiters — for instance WASP-39b, a giant planet 700 light-years away. JWST conducts what is called transit spectroscopy, in which, as the planet transits (moves across) the face of its star, some of that starlight passes through the planet's atmosphere. This light is absorbed by molecules within the planet's atmosphere, and different molecules absorb light at different wavelengths. JWST's spectrum of WASP-39b's atmosphere — showing the absorption lines, which allow astronomers to identify the molecules involved — is the most detailed look at an exoplanet's atmosphere yet conducted.

"We've already seen that JWST data is is just so good, so precise, that we are able to detect additional molecules in these distant exoplanet atmospheres that we've never really expected to see," said NASA Goddard's Knicole Colon, who also spoke at the SXSW event and who is JWST's deputy project scientist for exoplanet science.

One of these molecules, sulfur dioxide, was created in WASP-39b's atmosphere by photochemical reactions. In other words, by the action of sunlight on atoms and molecules in the atmosphere.

"We literally didn't think we'd be able to see [the results of these chemical reactions] with JWST," said Colon. "Even though we knew it'd be a great telescope, [the detection of sulfur dioxide was] still just that much better than expected."

This means that, as JWST studies and characterizes more and more exoplanets, new and exciting discoveries will almost certainly be on the menu, discoveries that will be able to teach astronomers about the formation and evolution of those planets. The mixture of gases in a planetary atmosphere, for instance, can give some indication as to how far from its star the planet formed.

Prior to JWST, studies of exoplanetary atmospheres were limited to hot Jupiters, but JWST is now beginning to target the atmospheres of smaller, Earth-sized planets, too. Observations of the rocky worlds of the TRAPPIST-1 system, for example, are ongoing, but because these planets are much smaller than hot Jupiters and orbit a faint red dwarf star, it will take longer for JWST to tease out the details from their atmospheres, if they even have atmospheres. However, in the next few years, some of the results from the TRAPPIST-1 planets and other similar worlds could transform how we view our own planet Earth in a cosmic context.

"We're still very much in the early days of deciphering all the exoplanet data," said Colon. "What we do want to do is compare those systems and say, 'Do they have any similarities to Earth?' I'm excited to see what we learn about those planets that are around the same size as our own. They might not always be the same temperature, they might not have surfaces with liquid oceans and all that, but we expect to still learn about their overall atmosphere. Is water in the atmosphere? Is there carbon dioxide? Is there anything familiar to us that we can connect to and relate to help us understand better [whether] there is other life out there?"

Related: The search for alien life

Whatever those answers are, they are coming, and the next few years are going to be tremendously exciting as JWST makes discoveries that could ultimately become historic milestones.

"The first couple of years of science with JWST is going to open the door to huge new questions and challenges that we have ahead of us on whether or not there could be life on another planet," said Milam.

Another mystery that captures the imagination just as much as the search for habitable exoplanets is that of the dark universe, specifically dark matter, which is the mysterious substance held responsible for the extra gravity observed in galaxies and galaxy clusters, and dark energy, the unknown force that is driving the acceleration in the expansion of the universe.

"We think that about 75% of the whole energy-matter content of the universe is this mysterious thing that we call dark energy, and another 20% is this other mysterious stuff called dark matter," said Milam. "When astronomers don't know what something is, we label it dark. It's astounding … the hundreds of billions of galaxies and the trillions of stars and countless planets, all of that only makes up about 5% of the whole universe. And the rest, the other 95%, we don't know what it is."

Dark matter is located in invisible haloes that surround galaxies, leading Milam to describe dark matter as the "scaffolding" in which galaxies sit.

"JWST is going to help us in learning specifically about dark matter," said Milam. "By studying how galaxies change over time, we're able to learn more about dark matter."

JWST won't be able to discover what dark matter is; that's up to the particle physicists. But by watching how dark matter behaves around galaxies, astronomers will be able to constrain some of its properties, which could help physicists nail down its nature. Researchers have been asking this question since Vera Rubin first identified the presence of dark matter in the 1970s, and JWST could help astronomers take some giant leaps forward in our understanding.

Meanwhile, the new discoveries from JWST keep on coming.

"I can say we have a lot of fantastic work that's coming out from the telescope," says Milam. "We have a queue of press releases for future publication that are coming out, so it is a very exciting time. Every week we release something, so just stay tuned and I'm sure you'll be astounded."

Follow Keith Cooper on Twitter @21stCenturySETI. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.