Ancient supermassive black hole is blowing galaxy-killing wind, James Webb Space Telescope finds

"To our knowledge, this galaxy-scale quasar-driven wind is currently the earliest one known."

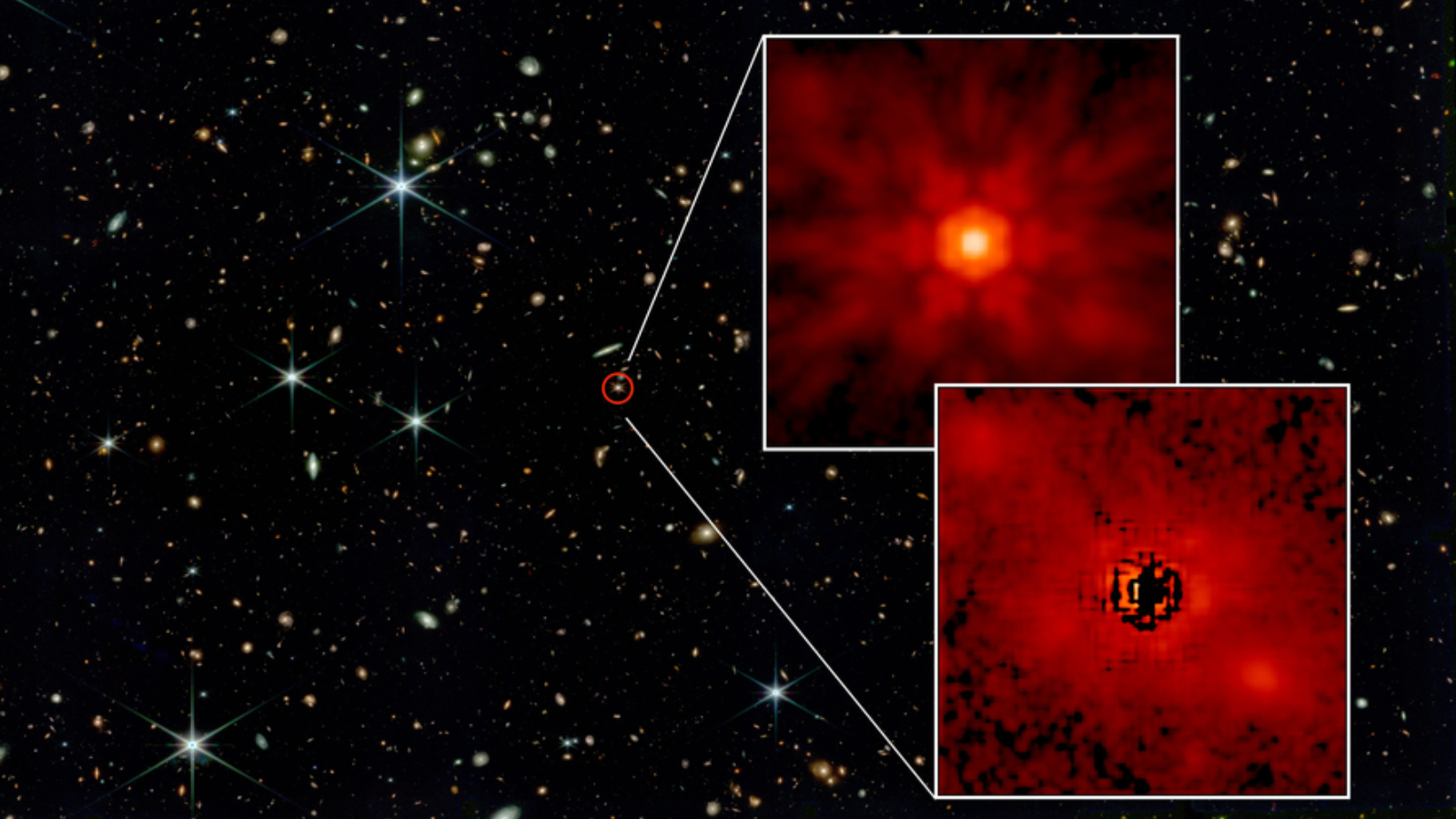

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers have spotted the earliest powerful "galaxy-size" wind blowing from a feeding supermassive black hole-powered quasar. The powerful wind is pushing gas and dust from its galaxy at incredible speeds, supressing star birth in its host galaxy.

This quasar, designated J1007+2115, is so distant that it is seen as it was just 700 million years after the Big Bang — when the 13.8 billion-year-old universe was just around 5% of its current age. Though this makes J1007+2115 just the third-earliest quasar ever seen, it is the earliest ever observed with a powerful, galaxy-size wind flowing from it.

The outflows from this quasar aren't just remarkable for their antiquity, though. The winds from J1007+2115 stretch out from the black hole at their source for a staggering 7,500 light-years, which is equivalent to around 3,750 solar systems lined up side-by-side! The material they shunt each year is equivalent to 300 suns at speeds equivalent to 6,000 times the speed of sound, researchers said.

"It is the third-earliest and third-most-distant quasar powered by an accreting supermassive black hole known today," discovery team leader and University of Arizona researcher Weizhe Liu told Space.com. "To our knowledge, this galaxy-scale quasar-driven wind is currently the earliest one known."

Related: How black-hole-powered quasars killed off neighboring galaxies in the early universe

The winds from this feeding central supermassive black hole may even be powerful enough to "kill" the host galaxy they rip through at 6,000 times the speed of sound, by depriving it of the matter needed to birth new stars.

How supermassive black holes get wind

All large galaxies are believed to have at their hearts a supermassive black hole, sporting a mass between millions and billions of times that of the sun. But not all of these black holes power quasars, the brightest sources of light in the cosmos.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That's because some supermassive black holes aren't surrounded by vast amounts of gas and dust that they can feed on. For instance, the supermassive black hole at the heart of our own galaxy, Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), is quiet and dim.

Other supermassive black holes are surrounded by a wealth of material swirling around them in a flattened cloud called an accretion disk that gradually feeds them. The immense gravitational influence of the central black hole causes powerful friction in accretion disks, heating this material and causing it to glow brightly.

These regions, called active galactic nuclei (AGNs) are so bright they can outshine the combined light of every star in the galaxy around them. When seen at great distances, these regions are called "quasars."

The powerful radiation emitted by accretion disks has another effect, too: It pushes away matter like gas and dust from around the AGN. These quasar winds can also push gas and dust away from the wider quasar-hosting galaxy.

With the aid of the JWST, the researchers were able to see that the material in the quasar winds from J1007+2115 is traveling at an incredible 4.7 million mph (7.6 million kph). As you might imagine, such powerful and far-reaching winds carry a vast amount of matter. Liu said that the quasar winds from J1007+2115 are carrying material with a mass equivalent to 300 suns each year.

The galaxy that houses J1007+2115 is rich in dense molecular gas and dust, the building blocks of stars, as seen by the JWST. The galaxy forms stars at a rate of around 80 to 250 solar masses every year. But the light from that galaxy has been traveling to us for 13.1 billion years, meaning it is likely quite different now. In particular, thanks to these quasar winds, starburst activity may not have continued for long.

The purging of gas and dust via these quasar winds will also cut off the food supply for the supermassive black hole driving them. This means that the growth of the supermassive black hole, with a mass estimated to be equal to that of 1 billion suns, may have also been halted today.

"The wind is pushing a large amount of gas outwards," Liu said. "This may suppress the star formation activity of the galaxy, which needs gas to form stars, and also the growth of the supermassive black hole itself, which also needs the accretion of gas."

This could mean that today, billions of years after the JWST sees it, this early galaxy is a dead galaxy and isn't growing much as a result of its star-forming material being purged and its star birth being curtailed.

Related: Brightest quasar ever seen is powered by black hole that eats a 'sun a day'

The team isn't done with quasar winds and investigating their influence on their host galaxies. They will continue to hunt them and may even uncover more that existed less than a billion years after the Big Bang.

"We now aim to look for more such galaxy-scale, quasar-driven winds in the

very early universe and get to know their properties as a population," Liu concluded.

A pre-print version of the team's research is featured on the paper repository arXiv.

Editors note 10/8: The jet's length was updated from being equivalent to 25 solar systems in length to 3,750 solar systems in length. The "speed of light" was replaced with the "speed of sound."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

NASA spacecraft spots monster black hole bursting with X-rays 'releasing a hundred times more energy than we have seen elsewhere'

Could we use black holes to power future human civilizations? 'There is no limitation to extracting the enormous energy from a rotating black hole'

-

Questioner "...7,500 light-years, which is equivalent to around 25 solar systems lined up side-by-side."Reply

The Solar system isn't 300 lys across!

What?!? -

CatDad007 Reply

I didn't even notice that - my attention was entirely focused on the apparent "6000 times the speed of light".Questioner said:"...7,500 light-years, which is equivalent to around 25 solar systems lined up side-by-side."

The Solar system isn't 300 lys across!

What?!? -

Smilingp This is a perfect example of why you don't write science articles while drunk/high/driving a car or anything similar. 25 solar systems lined up equals 7,500 light years?!!! Matter travelling 6,000 times the speed of light?!!!Reply -

6000x This article is trash. First it's claimed the ejection speed is 6000 times the speed of light, which is nonsense. Then, later, it's stated to be 6000 times the speed of sound, which is also total nonsense in this context.Reply

Our solar system is maybe between .5-2 light years in diameter, depending on where you draw the boundary... Even being generous, 300 x 2 isn't hard math, and nowhere near 7,500.

Reads like it's written by AI without any attempt to proof at all. Absolute garbage content, you should be ashamed. -

Spaced62 Reply

So many new journalists on the Internet and no editors, this story is so full of misinformation a Trump supporter would believe it.Admin said:The James Webb Space Telescope has spotted the earliest supermassive black hole-driven quasar wind ever seen, pushing away matter at 6,000 times the speed of sound and killing its host galaxy.

Ancient supermassive black hole is blowing galaxy-killing wind, James Webb Space Telescope finds : Read more

Other than 6,000 times the speed of light and the size of the solar system, which have already been pointed out, wouldn't it reasonably be assumed if it's the 3rd earliest quasar ever discovered it's also the 3rd most distant?

Now I can't even rely on your articles. -

Livyatan Reply

Came hear to say that too and the 6,000 light year speed gave me a chuckle as well. Imagine if we could build a solar sail to harness those winds we could tool across the Milky Way in about 17 years. 😊Questioner said:"...7,500 light-years, which is equivalent to around 25 solar systems lined up side-by-side."

The Solar system isn't 300 lys across!

What?!? -

Helio Reply

Same here. It was stated later as 6,000x the speed of sound. But that's actually worse since the speed of sound varies with density. The speed of sound, say, in a nebulae is so low that supersonic flows are common and likely contribute to the first steps toward some planetary formations.Livyatan said:Came hear to say that too and the 6,000 light year speed gave me a chuckle as well.