James Webb Space Telescope detects a surprise supernova

The detection promises to open up a completely new area of research possibilities.

The James Webb Space Telescope has surprised scientists by unexpectedly detecting its first supernova, an explosion of a dying star. The detection could possibly open up an entirely new area of research possibilities, scientists say.

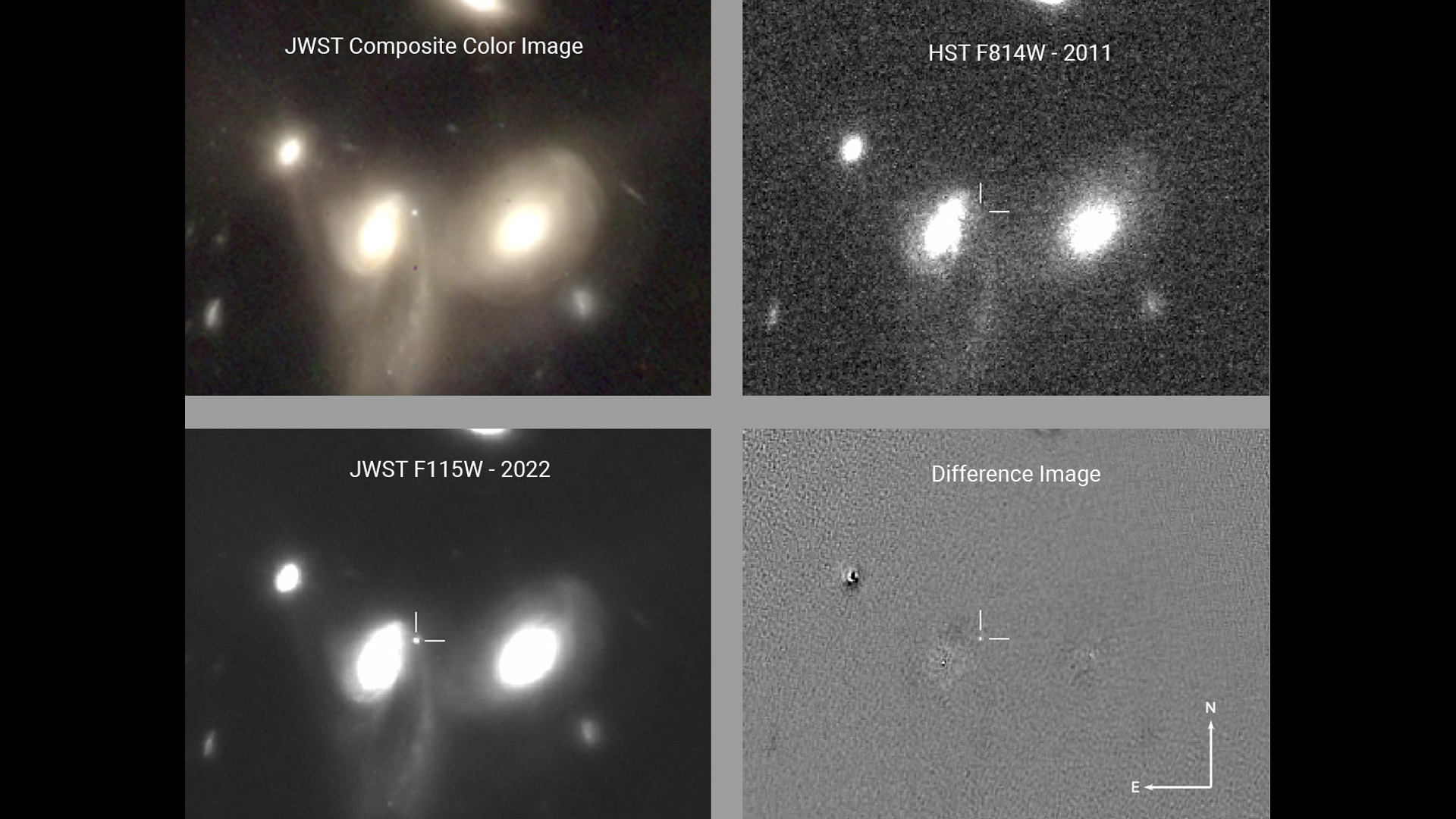

Just a few days after the start of its science operations, the James Webb Space Telescope's NIRCam camera spotted an unexpected bright object in a galaxy called SDSS.J141930.11+5251593, some 3 to 4 billion light-years from Earth. The bright object dimmed over a five-day period, suggesting that it could have been a supernova, caught by sheer luck shortly after the star exploded. (The astronomers compared the new observations with archived data from the Hubble Space Telescope to confirm the light was new.)

The discovery is surprising as the James Webb Space Telescope wasn't built to search for supernovas; a task usually performed by large-scale survey telescopes that scan vast portions of the sky at short intervals. Webb, on the other hand, looks in great detail into a very small area of the universe. For example, the deep field image released by U.S. President Joe Biden in mid-July, covered an area about as large as a grain of sand.

Gallery: James Webb Space Telescope's 1st photos

Since the detection came already in the first week of Webb's science operations, astronomers think that the depth of Webb's images might actually compensate for the small area. Each deep field image includes hundreds of galaxies — which means hundreds of opportunities to spot a supernova.

The early detection suggests the telescope might be able to see supernovas on a regular basis, according to Inverse. That would be exciting, particularly because Webb is expected to see the earliest galaxies that formed in the universe, in the first hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang. Combine that ancient view with its unexpected supernova detection and Webb might be able to capture the explosion of one of the first-generation stars that lit up the universe after the dark early ages. These stars, astronomers think, had a much simpler chemical composition than stars that were born in later epochs.

"We think that stars in the first few million years would have been primarily, almost entirely, hydrogen and helium, as opposed to the types of stars we have now," Mike Engesser, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute, which operates Webb, who led the team that announced the detection, told Inverse. "They would have been massive — 200 to 300 times the mass of our sun, and they would have definitely lived a sort of 'live fast, die young' lifestyle. Seeing these types of explosions is something we haven't really done yet."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The supernova detected marks the death of a much younger star, one only 3 to 4 billion years old, but it's a promising start for a telescope built to do something rather different.

Supernovas are tricky to detect since the explosion itself lasts only a fraction of a second. The bright bubble of dust and gas that these stellar deaths generate fades after only a few days, so a telescope needs to be looking in the right direction at the right time to catch one.

Now astronomers must hope that Webb's first supernova wasn't just beginner's luck.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.