James Webb Space Telescope and Hubble will help NASA's Juno probe study Jupiter's volcanic moon Io

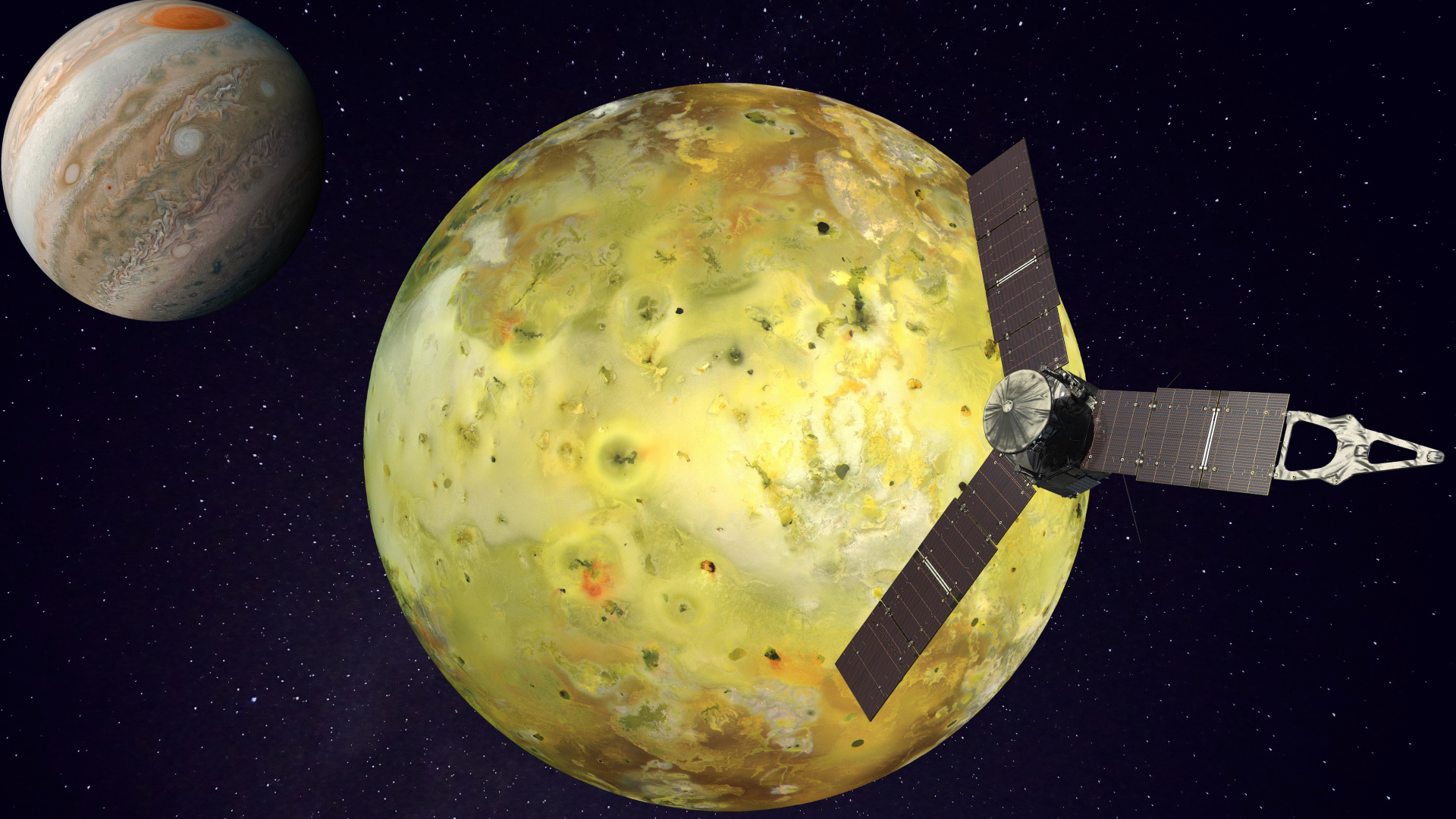

The telescopes will team up to assist NASA's Juno spacecraft the next time it flies by Io, our solar system's most volcanic body.

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Hubble Space Telescope are set to team up and observe the solar system's most volcanic body: A moon of Jupiter named Io.

The two space telescopes will remotely collect data about the intriguing world, then that information will be put to use by NASA's Juno spacecraft. More specifically, the data will help guide Juno during future flybys of Io, as the probe investigates how the highly volcanic moon may contribute to plasma present in the environment around Jupiter.

The investigation will conducted by the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI), an organization that has been granted JWST and Hubble observing time by the Space Telescope Science Institute. The SwRI team will collect Io data with Hubble during 122 of the telescope's orbits around Earth, as well as supplement those findings with almost five hours of JWST observing time.

"The timing of this project is critical," Kurt Retherford, principal investigator of the campaign and SwRI researcher, said in a statement. "Over the next year, Juno will buzz past Io several times, offering rare opportunities to combine in-situ and remote observations of this complex system."

Related: Massive, months-long volcanic eruption roils Jupiter's moon Io

"We hope to gain new insights into Io’s dramatic volcanism, plasma-moon interactions and the neutral gas and plasma populations that propagate through Jupiter's vast magnetosphere and trigger intense Jovian auroral emissions," Retherford added.

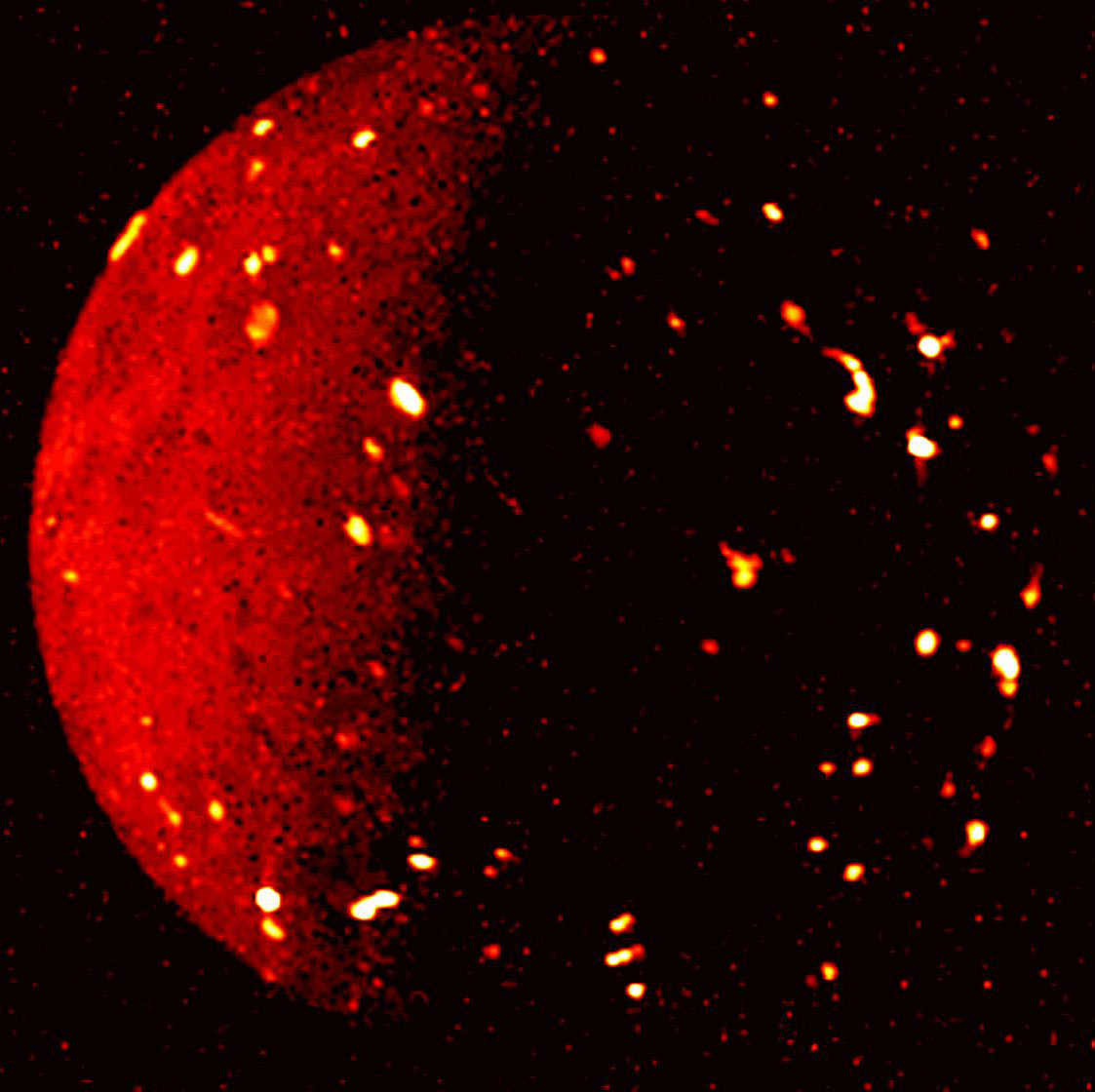

NASA estimates that Io's surface is punctuated by hundreds of actively erupting volcanoes that can blast lava dozens of miles into the Jovian moon's thin, waterless atmosphere.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Io, which is around the size of Earth's moon and the innermost Galilean satellite of Jupiter, is believed to be so extremely volcanic because the gravitational influences of its host planet generate tidal forces that squash and squeeze this moon. Other Jovian moons, including the rest of the Galilean satellites, have a similar effect on Io too, further exacerbating this gravitational storm.

These forces are so powerful, in fact, that they can provoke the surface of Io to rise and fall by as much as 330 feet (100 meters). And as you might expect, such extreme volcanism affects the entire Jovian system.

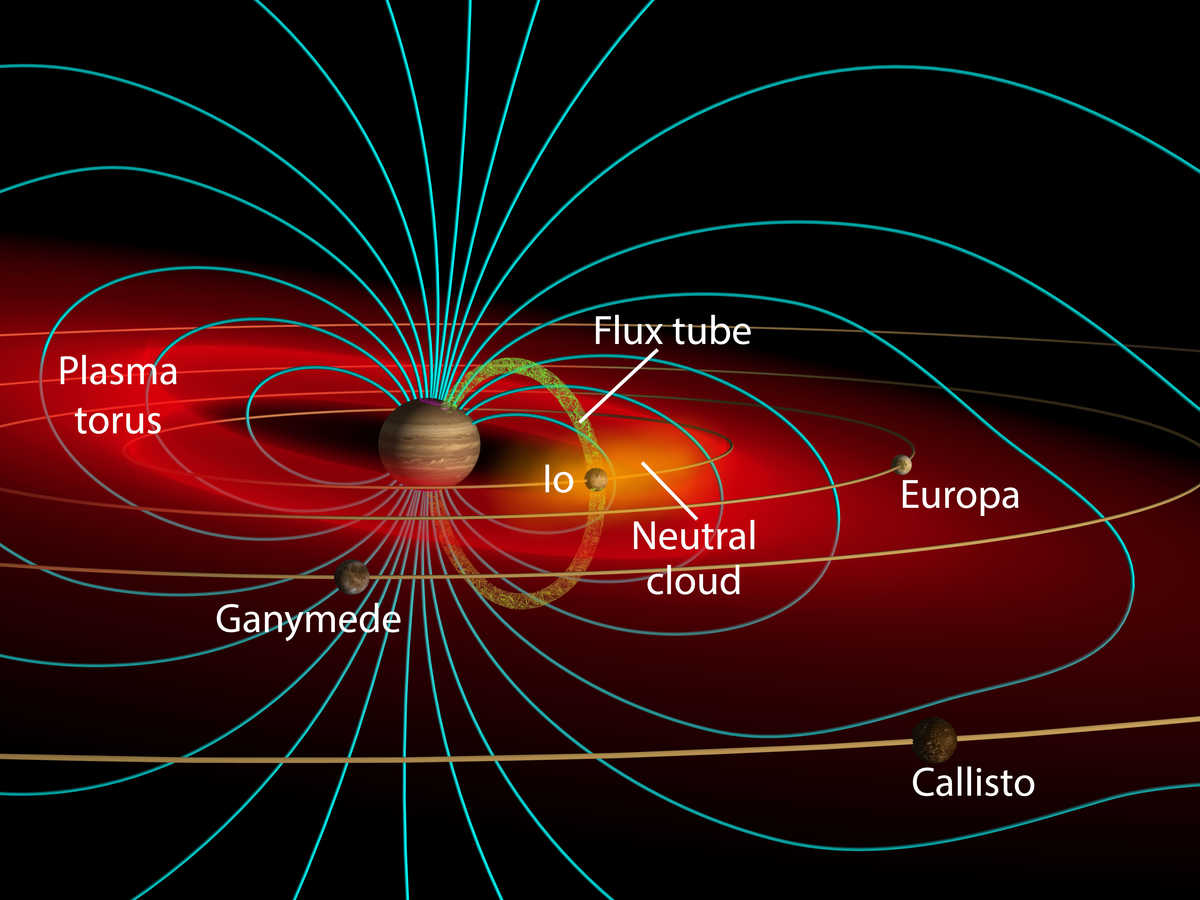

Io's extreme volcanism drives donut cloud around Jupiter

Particles escaping from Io's atmosphere, for instance, are believed to be a major source of material trapped in Jupiter's magnetic field. These escaping atmospheric gases are ionized, meaning they undergo a process in which extreme heat rips electrons from atoms to create a dynamic sea of charged particles.

"Most of these materials don’t actually escape straight out of the volcanoes but rather are associated with the sublimation of sulfur dioxide frost from Io's dayside surface," Katherine de Kleer, project co-investigator and scientist at Caltech, said in the statement. "The interaction between Io’s atmosphere and the surrounding plasma provides the escape mechanism for gases released from the moon's frozen surface."

This forms a doughnut-shaped cloud of charged particles, called the Io Plasma Torus (IPT), surrounding Jupiter. When electrons collide with ions in the IPT, they create ultraviolet radiation that can be detected by telescopes here on Earth and in space.

Continued investigation is needed to fully understand the IPT, however, because it is difficult to assess how strong its connection to Io's volcanism actually is. It's also an open question as to what effects Io has on other bodies in the Jovian system, such as those other large Galilean moons.

"For example, how much sulfur is transported from Io to Europa's surface? How do auroral features on Io compare with aurora on Earth — the northern lights — and Jupiter?" Fran Bagenal, project co-principal investigator and researcher at the University of Colorado at Boulder, said in the statement.

The team believes the key to better understanding these connections is by investigating the Jovian system as a whole rather than in pieces. And that requires more data than even Juno, as impressive as it is, can provide.

"Hey Hubble ... watch this!"

Juno has been investigating the Jovian system and its environment since July 4, 2016, when it arrived in the vicinity of the gas giant and its moons after a 1.7 billion-mile journey from Earth. This was a journey that took five years to complete.

Since then, the spacecraft has completed several flybys of both Jupiter and its large moons, notably Europa. It last flew past Io on July 30, coming within around 13,700 miles (22,000 kilometers) of the fiery moon while collecting data about its atmosphere and magnetic field. Juno will get particularly close to Io again on Dec. 30 of this year then again on Feb. 1, 2024.

On Sept. 20, however, Juno will make a more distant pass of Io that will be of particular interest to the SwRI team. This flyby of Io will be timed such that it can be observed by Hubble and the JWST simultaneously.

That means the two telescopes will get the chance to team up and observe what Juno sees, but at a distance, giving scientists the holistic view of the Jovian system they're after.

"The chance for a holistic approach to Io investigations has not been available since a series of Galileo spacecraft flybys in 1999 to 2000 were supported by Hubble with a prolific 30-orbit campaign," Retherford concluded. "The combination of Juno’s intensive in-situ measurements with our remote-sensing observations will undoubtedly advance our understanding of Io's role in driving coupled phenomena in the Jupiter system."

Even though future missions to Jupiter and its moons are in the cards, with the Europa Clipper and Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) set to arrive at the Jovian system between 2029 and 2031, neither will fly by Io.

That means, according to the SwRI, another chance to make these kinds of observations won't arise until at least the 2030s.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.