James Webb Space Telescope watches infant galaxies bringing light to the early universe

"The stars in these young galaxies were remarkable, producing just the right amount of radiation to excite the surrounding gas. This gas, in turn, shone even brighter than the stars themselves."

Baby galaxies in the early universe ignited gas to trigger explosions of intense star formation, according to new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST).

Many early galaxies like the ones the JWST detected were rich with glowing gas so bright that the gas itself could outshine stars emerging from within.

These new findings reveal just how common such shimmering, infant, gassy galaxies were when the 13.8 billion-year-old universe was around only 2 billion years old. The team behind this research found that almost 90% of the galaxies had so-called "extreme emission features," meaning they exhibited all that glowing gas.

"The stars in these young galaxies were remarkable, producing just the right amount of radiation to excite the surrounding gas. This gas, in turn, shone even brighter than the stars themselves," research lead author and ARC Centre of Excellence for All Sky Astrophysics in 3 Dimensions (ASTRO 3D) scientist Anshu Gupta said in a statement. "Until now, it was challenging to understand how these galaxies were able to accumulate so much gas.

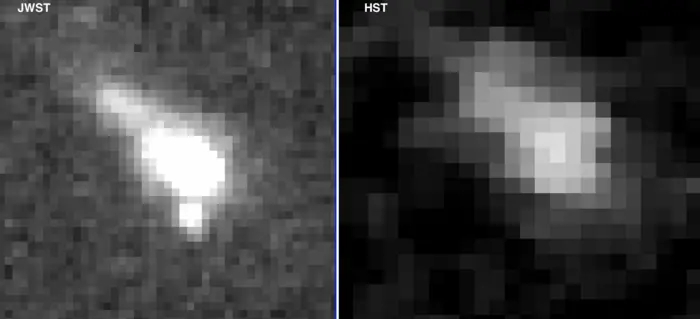

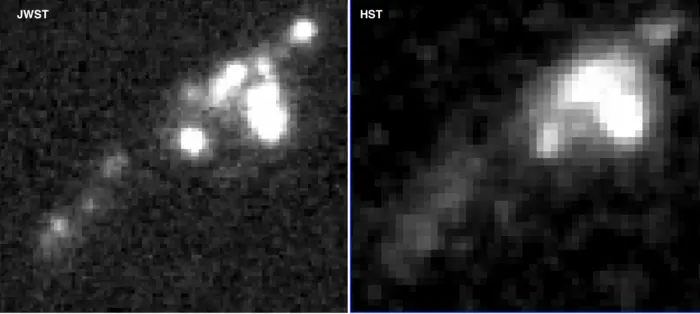

"Our findings suggest that each of these galaxies had at least one close neighboring galaxy. The interaction between these galaxies would cause gas to cool and trigger an intense episode of star formation, resulting in this extreme emission feature."

Related: James Webb Space Telescope could soon solve mysteries of the Milky Way’s heart

The discovery confirms the assumptions of astronomers who suspected these extreme galaxies are indicators of intense interactions in the early universe.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"What’s really exciting about this piece is that we see emission line similarities between the very first galaxies to galaxies that formed more recently and are easier to measure," team member and Curtin University researcher Ravi Jaiswar said. "This means we now have more ways to answer questions about the early universe, a period that is technically very hard to study."

The James Webb Space Telescope is paying off

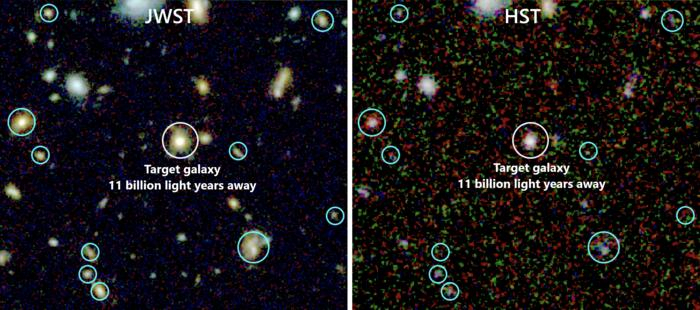

This new conclusion is yet another example of how the JWST was worth every penny of its $10 billion cost — prior to this, astronomers simply hadn’t been able to get a clear picture of star-forming galaxies that existed around 12 billion years ago.

"The data quality from the James Webb telescope is exceptional. It has the depth and resolution needed to see the neighbors and environment around early galaxies from when the universe was only 2 billion years old," Gupta said. "With this detail, we were able to see a marked difference in the number of neighbors between galaxies with the extreme emission features and those without."

The data used by the team was collected as part of the JWST Advanced Deep Extragalactic Survey (JADES) survey, the goal of which is to explore the earliest galaxies and open the door to future insights.

"Prior to JWST, we could only really get a picture of really massive galaxies, most of which are in really dense clusters, making them harder to study," Gupta concluded. "With the technology available then, we couldn’t observe 95% of the galaxies we used in this study.

"The JWST has revolutionized our work."

The team’s research is published in the Astrophysical Journal.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.