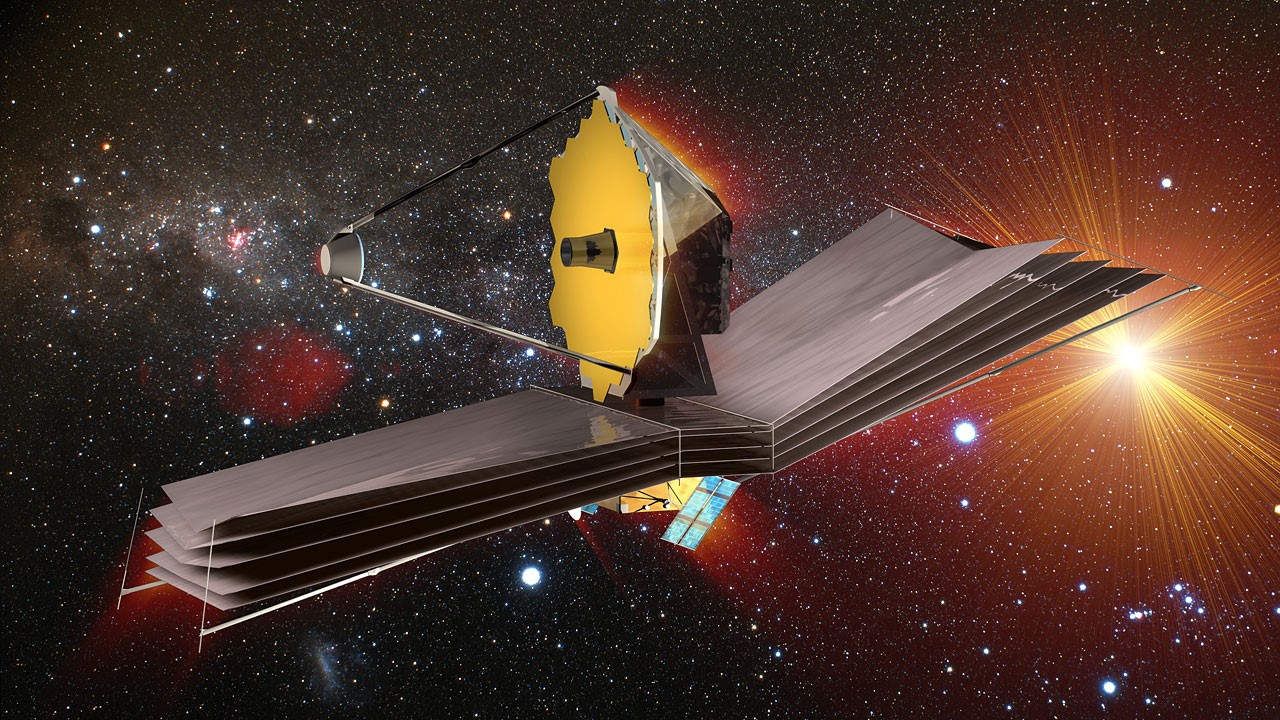

Why doesn't the James Webb Space Telescope have any cameras onboard?

Engineers must make do with traditional telemetry because of a lot of practical problems.

The public is now used to seeing space up close, thanks to cameras watching everything from satellites deploying to a spacesuit-clad "dummy" cruising in a Tesla — so why doesn't NASA's giant new observatory have any cameras on board?

It has to do with light and heat, Julie Van Campen, deputy commissioning manager for the James Webb Space Telescope at NASA's Goddard Space Center in Maryland, said during a live broadcast Tuesday (Jan. 4) showing the last stages of the tricky sunshield deployment.

Webb launched on Dec. 25 and is now on a month-long journey to its observing destination, nearly 1 million miles (1.5 million kilometers) from Earth. But engineers in charge of the telescope's nerve-wracking development have no photographs to work from.

Live updates: NASA's James Webb Space Telescope mission

Related: How the James Webb Space Telescope works in pictures

Van Campen noted that Webb's multi-decade development began when portable cameras were not widely available. But even if a camera was included on board, it might mess up the sensitive optics on Webb, which are sensitive in infrared to gaze back at the young universe.

So the first challenge for an onboard camera would be overcoming that the telescope literally operates in the black: "Looking at the telescope, it would be dark," Van Campen explained of a theoretical camera's view.

"We would need some kind of light system on a camera system," Van Campen continued. "We would have problems if we wanted to do flash photography, obviously. Our mirrors are very sensitive. Our optics inside are very sensitive, and most importantly, [so are] our detectors all the way deep inside of our instruments."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Another problem with deploying cameras would be interference with keeping Webb cool. Webb must operate at a very low temperature so as not to disturb its infrared observations, which means attaching a camera would be very complicated.

"Plastics fall apart" in the cold, Van Campen said, "and they shrink and crack glues ... to make something that would work in the cryogenic temperatures on the cold side of the sunshield will take a lot of engineering and design."

And running heat cables out to keep the cameras warm could cause Webb to accidentally study the heat signature of the cables, rather than the signature of the universe.

So Van Campen said the engineers are relying on traditional data transmitted from the telescope. That data, known as telemetry, does the job — even if it's perhaps not quite as satisfying.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.