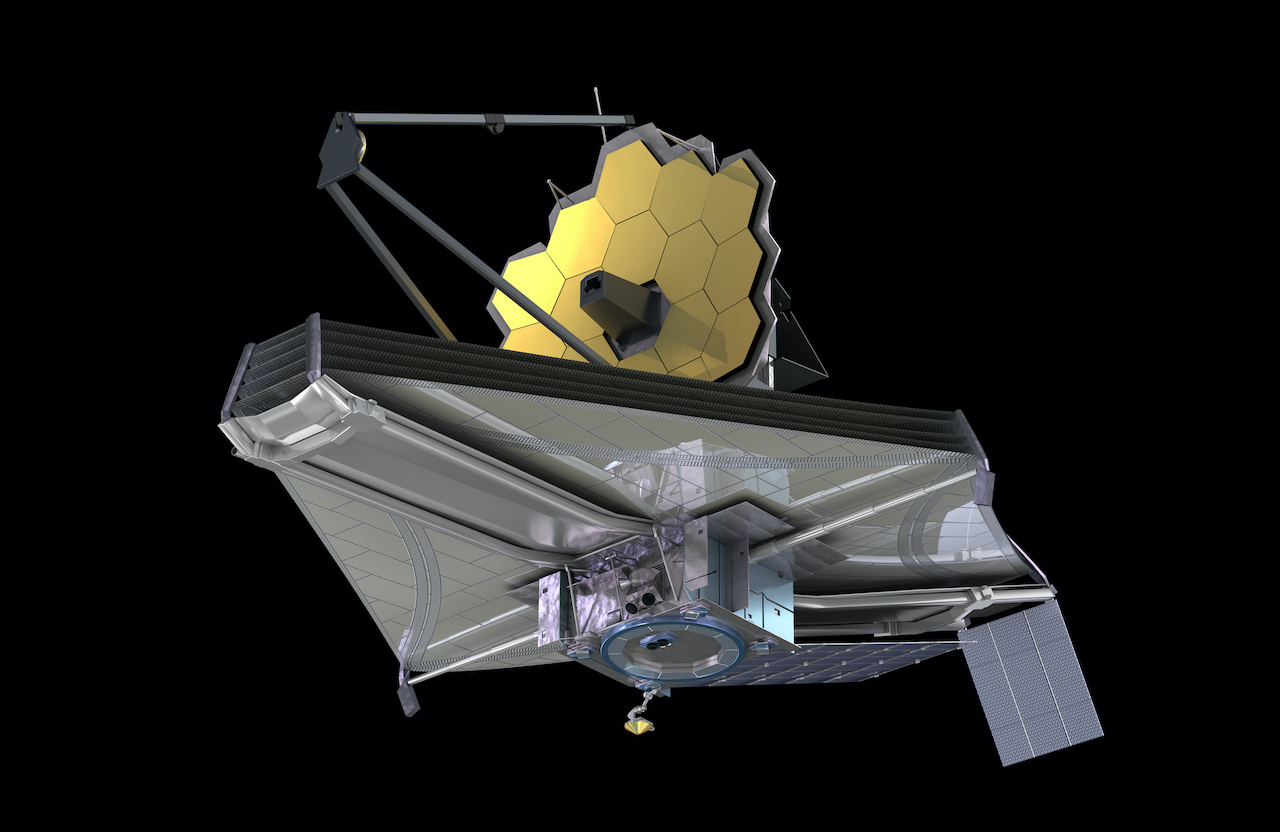

James Webb Space Telescope's supercold camera is now ready for science

The camera images the universe in mid-infrared wavelengths and analyzes chemical compositions.

Teams preparing the James Webb Space Telescope for the commencement of its science operations have concluded the fine-tuning of the second of its four cutting-edge instruments ahead of the reveal of the telescope's first science-grade images less than two weeks from now.

The Mid-Infrared instrument (MIRI) combines a camera that images the universe in mid-infrared wavelengths and a spectrograph that can capture light spectra of the observed stars and galaxies. These spectra, essentially the fingerprints of how celestial objects absorb light, reveal their chemical composition.

MIRI operates in four modes, which allow the instrument to focus on different aspects of the studied objects. The engineering team concluded the testing of MIRI by checking its coronagraphic imaging mode, which enables astronomers to mask the bulk of a star and see just the surrounding glow of the stellar atmosphere, the corona. In the corona, the James Webb Space Telescope will be able to see exoplanets orbiting those distant stars.

Related: James Webb Space Telescope's powers will be revealed in just weeks and scientists can't wait

"We are thrilled that MIRI is now a functioning, state-of-the-art instrument with performances across all its capabilities better than expected," Gillian Wright, MIRI European principal investigator at the U.K. Astronomy Technology Center, which co-developed the instrument, said in a statement.

MIRI, developed jointly by NASA, the European Space Agency (ESA) and a range of science institutions in Europe and America, requires the coldest temperature of all the Webb instruments to function properly.

Hidden behind its giant sunshield, the whole telescope had to cool down to minus 370 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 223 degrees Celsius) after its arrival at the Lagrange Point 2, a gravitationally stable point some 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) away from Earth. Because Webb observes infrared light, which is essentially heat, any warmth from the telescope itself would dazzle its super-sensitive sensors.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

MIRI, however, needed to get even colder — minus 447 degrees F (minus 266 degrees C), which is only 12 degrees F (7 degrees C) above absolute zero, the temperature at which the motion of atoms stops.

To achieve such a freezing cold, MIRI is fitted with electrical cryocoolers.

The Webb teams previously concluded the commissioning of the Fine Guidance Sensor/Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (FGS/NIRISS). Mission personnel still have some work to do on the Near Infrared Camera (NIRCAM) — the main imager that will be able to see the oldest, most distant galaxies — and the Near InfraRed Spectrograph (NIRSpec), a powerful spectrograph that will be able to take spectra of up to 100 galaxies at once.

First science-quality images from the $10 billion telescope, which is the most complex and expensive space observatory ever built, will be released to the public on July 12 during a live event you can watch here at Space.com.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.