James Webb Space Telescope nails secondary mirror deployment

"We actually have a telescope."

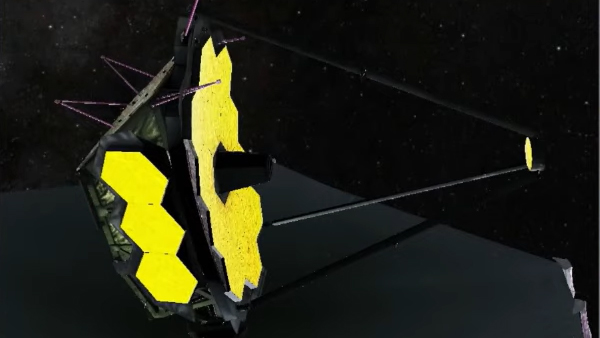

The James Webb Space Telescope achieved another major milestone today, successfully extending its secondary mirror as it continues to sail seamlessly through its never-before-conducted deployment sequence on the way to its destination.

The 2.4-foot-wide (0.74 meters) secondary mirror sits attached to a tripod opposite the main mirror. Its task is to concentrate the light collected by the gold-coated main mirror into an opening at the main mirror's center. Through this opening, the light reaches the third mirror, which reflects it to the telescope's instruments.

The secondary mirror travelled to space stowed on top of the main mirror, attached to three 26-feet-long (8 m) legs that form its supporting tripod.

On Wednesday (Jan. 5), operators at Webb's operations center at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore released latches that secured the legs in place during launch. After having first performed a very small move to ensure the motors worked well, they then commenced the deployment procedure, which saw the legs extend and fall into place over the course of 10 minutes. NASA streamed the maneuver live with commentary on its TV channel.

Related: A James Webb Space Telescope astronomer explains how to send a giant telescope to space — and why

The confirmation that the mirror was in place arrived at about 11:30 a.m. EST (1630 GMT). The operators then took another 30 minutes to lock the tripod in place with several latches to ensure it will remain stable for the duration of Webb's at least ten-year scientific mission.

"This is unbelievable. We are now at a point where we're about 600,000 miles [1 million kilometers] from Earth, and we actually have a telescope," Bill Ochs, the James Webb Space Telescope project manager at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in the webstream. "So congratulations to everybody."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Once it's latched, it's complete and we do not ever come back and adjust this again," added Webb's deputy commissioning manager Julie van Campen, also of NASA Goddard.

The secondary mirror deployment comes only a day after the operators completed the most challenging part of Webb's self-building sequence — the unfurling and tensioning of the telescope's tennis-court-sized sunshield.

On Thursday (Jan. 6), the operators will unpack a radiator on the back of the telescope, designed to remove heat from the scientific instruments. They will then move on to assembling the main 21-foot (6.4 m) mirror, which due to its size also had to be folded for launch.

"In the first 12 days after the launch, we focused on the spacecraft system deployments like the solar array, the communication system and the sunshield," van Campen said. "Today, we have switched gears and moved to the optical elements of the telescope. And then, in the final part of the commissioning, we will switch gears again and focus on the science instruments."

The telescope's deployment sequence was a source of apprehension with some describing it as nerve-wracking. Webb's scientific objective, to see the first stars and galaxies that formed in the universe in the first hundreds of millions of years after the Big Bang, required an observatory of an unprecedented size and complexity. For this reason, the telescope is so big that no existing rocket could launch it without having it folded up first. The mission stretched engineers and technologies to their limits, leading to a plethora of ingenious engineering solutions. Those solutions, which see the telescope self-assemble in space like a transformer, have never before been used in space. The extensive testing program that took years to complete is, however, paying off.

"It has worked incredibly well over the past 12 days," van Campen said. "We've had moments of excitement and lots of tension as we kind of wait to see how things work out. But it's been going great and we are slightly ahead of schedule."

The telescope won't be ready for science until this summer. It will take more than 100 days for Webb to cool down to its operational temperature of minus 400 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 235 degrees Celsius). Only in such extreme cold will the telescope be able to detect the faintest infrared signals from the most distant stars and galaxies.

Van Campen explained that operators can't monitor the deployments visually as no existing camera technology would survive in the extreme cold behind the sunshield. Electronic interference from the cameras could also affect the scientific observations. Instead, operators use a computer-based visualization tool that receives telemetry data from the telescope.

The telescope is on its way to the Earth-sun Lagrange Point 2 some 930,000 (1.5 million km) away from our planet. At L2, Webb will orbit the sun hidden behind Earth, held in a stable position by the delicate interplay of the gravitational forces of the two bodies.

The telescope is expected to reach its destination by the end of January, fully deployed. The $10 billion mission, the most complex and expensive space observatory ever built, is expected to revolutionize astronomy, providing previously impossible insights into star and planet formation, the chemistry of exoplanets and the behaviour of comets and asteroids at the outer fringes of the solar system.

Follow Tereza Pultarova on Twitter @TerezaPultarova. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.