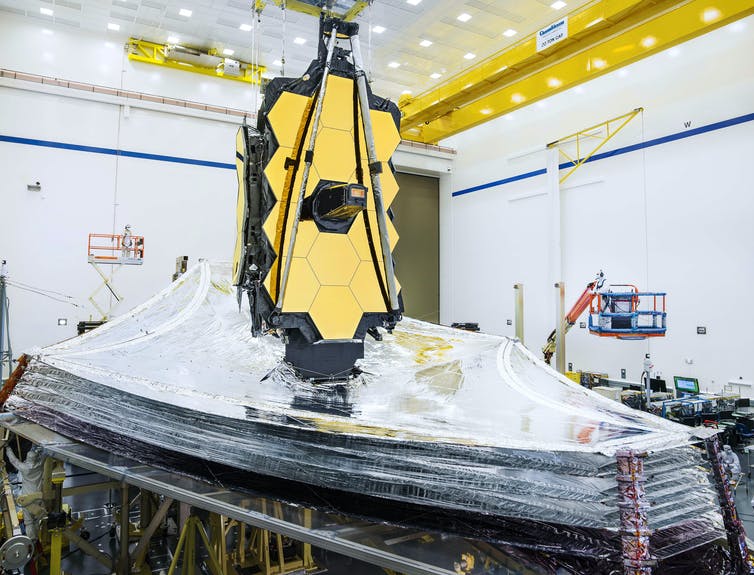

One of the James Webb Space Telescope's most nail-biting deployment steps is safely in the books.

The $10 billion observatory unfurled its huge sunshield on Friday (Dec. 31), carefully unfolding the five-layer structure by sequentially deploying two booms.

"Shine bright like a diamond. With the successful deployment of our right sunshield mid-boom, or 'arm,' Webb’s sunshield has now taken on its diamond shape in space," mission team members said via Webb's Twitter account Friday night.

Live updates: NASA's James Webb Space Telescope mission

Related: How the James Webb Space Telescope works in pictures

Shine bright like a diamond 💎With the successful deployment of our right sunshield mid-boom, or “arm,” Webb’s sunshield has now taken on its diamond shape in space. Next up: tensioning the 5 sunshield layers! https://t.co/6G2caS1djY #UnfoldTheUniverse pic.twitter.com/q0iuHdnKlNJanuary 1, 2022

The sunshield is one of the most crucial and complicated features of Webb, which launched on Dec. 25 to seek out faint heat signals from the early universe. Detecting such signals requires that Webb keep its instruments and optics extremely cold, and the sunshield will help it do just that by reflecting and radiating away solar energy.

The shiny silver shield measures 69.5 feet long by 46.5 feet wide (21.2 by 14.2 meters) when fully deployed — far too large to fit inside the protective payload fairing of any currently operational rocket. So it was designed to launch in a highly compact configuration and then unfold once Webb got to space.

That deployment is an elaborate, multistep process with many different potential failure points that could sink the entire mission.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Webb's sunshield assembly includes 140 release mechanisms, approximately 70 hinge assemblies, eight deployment motors, bearings, springs, gears, about 400 pulleys and 90 cables totaling 1,312 feet [400 m]," Webb spacecraft systems engineer Krystal Puga, who works at Northrop Grumman, the prime contractor for the mission, said in a video about Webb's deployments that NASA posted in October.

Sunshield deployment began on Tuesday (Dec. 28) when Webb lowered the two pallets that hold the five-layer structure. Additional steps followed over the next few days. On Thursday (Dec. 30), for example, the observatory released the cover that had protected the sunshield during its time on Earth and launch to space.

That cover complicated Friday's activities a bit: The Webb team delayed boom deployment by a few hours to make sure that the cover had fully rolled up as planned, and as needed.

"Switches that should have indicated that the cover rolled up did not trigger when they were supposed to," Patrick Lynch, deputy chief of the communications office at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, wrote in a blog post Friday.

"However, secondary and tertiary sources offered confirmation that it had," Lynch added. "Temperature data seemed to show that the sunshield cover unrolled to block sunlight from a sensor, and gyroscope sensors indicated motion consistent with the sunshield cover release devices being activated."

Webb team members initiated deployment of the port (lefthand) mid-boom at 1:30 p.m. EST (1830 GMT) on Friday, Lynch wrote, and the activity wrapped up at 4:49 p.m. EST (2149 GMT). Extension of the starboard mid-boom began at 6:31 p.m. EST (2331 GMT) and was done by around 10:13 p.m. EST (0313 GMT on Jan. 1), Lynch wrote in another blog post.

Related: Why the James Webb Space Telescope's sunshield deployment takes so long

Unfurling the sunshield is a huge milestone, so Webb team members are likely breathing big sighs of relief after Friday's success. But the sunshield work isn't done yet; its five thin Kapton layers must still be brought up to the proper tension, which the mission team aims to do over the weekend.

After that's done, the focus will shift to deploying Webb's secondary mirror and its 21.3-foot-wide (6.5 m) primary mirror. Those tasks are expected to be complete by Jan. 7 at the earliest, but deployment timelines are flexible, so don't be shocked (or concerned) if that target isn't met.

Locking the mirrors into their proper place will bring Webb's complex main deployment phase to an end. The next major milestone to follow will be an engine burn, scheduled for 29 days after launch, that will insert Webb into orbit around its final destination: the Sun-Earth Lagrange Point 2 (L2), a gravitationally stable spot 930,000 miles (1.5 million kilometers) from our planet.

Webb team members will still have a lot of work to do after the observatory arrives at L2. They'll have to precisely align the 18 segments of Webb's primary mirror so the pieces work together as a single light-collecting surface, for example, and check out and calibrate the telescope's four scientific instruments.

Regular science operations are expected to start six months after launch, in the summer of 2022. For at least five years after that, Webb will study some of the universe's first stars and galaxies, hunt for intriguing compounds in the atmospheres of nearby exoplanets and make a variety of other potentially transformative cosmic observations.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.