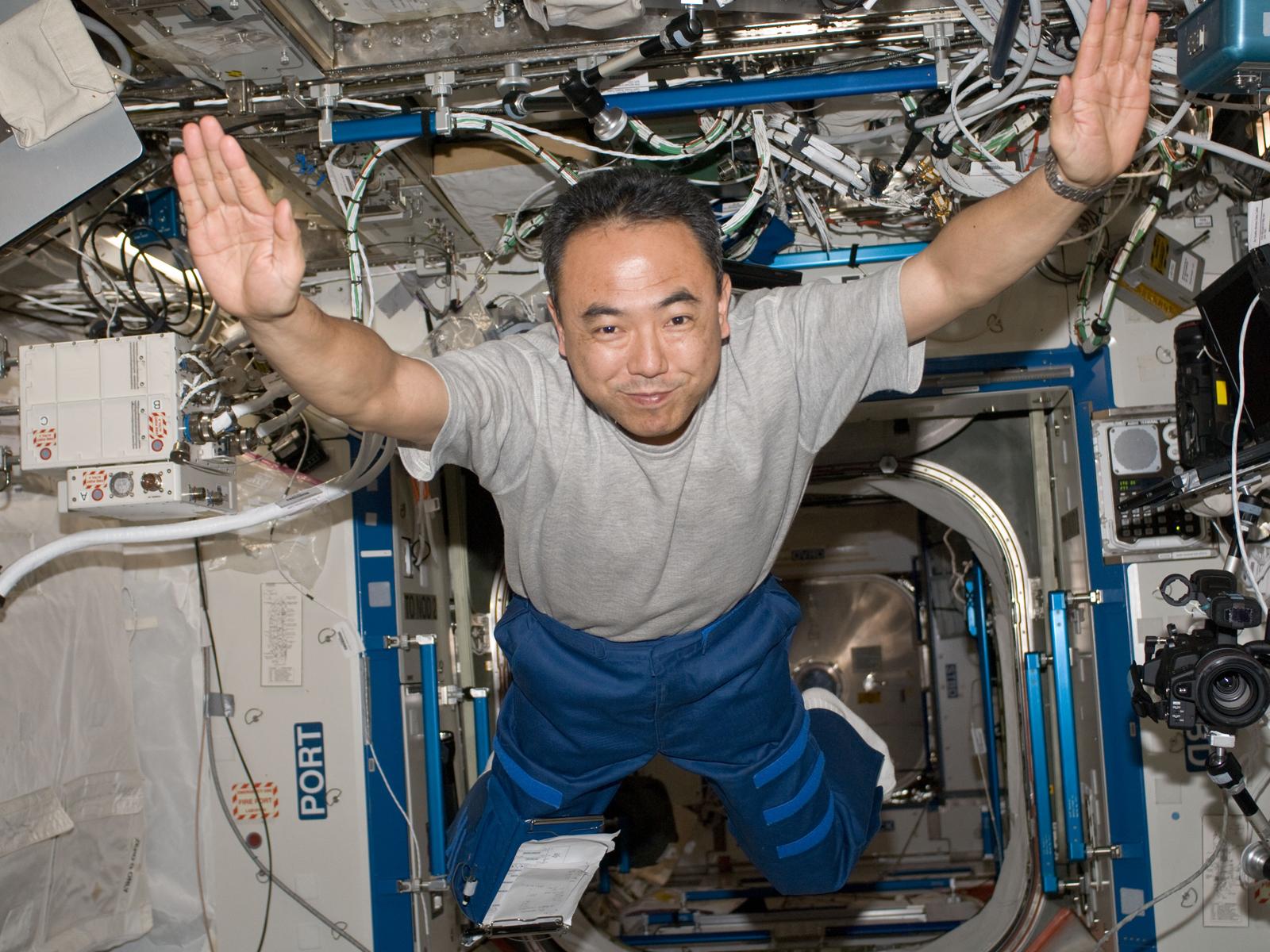

Japanese astronaut keeps International Space Station mission amid research scandal

He's scheduled to launch next year.

A Japanese astronaut will not lose his 2023 mission to the space station despite his involvement in a research scandal, according to media reports.

Astronaut Satoshi Furukawa and his team, however, will be "appropriately" punished for "fabricated" and "altered" research study data simulating astronaut work on the International Space Station, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) said in English-language reports from United Press International (UPI) and the Japan Times.

Furukawa, originally trained as a medical doctor and surgeon, was said to have had a supervisory role in the research and no direct involvement otherwise in the work.

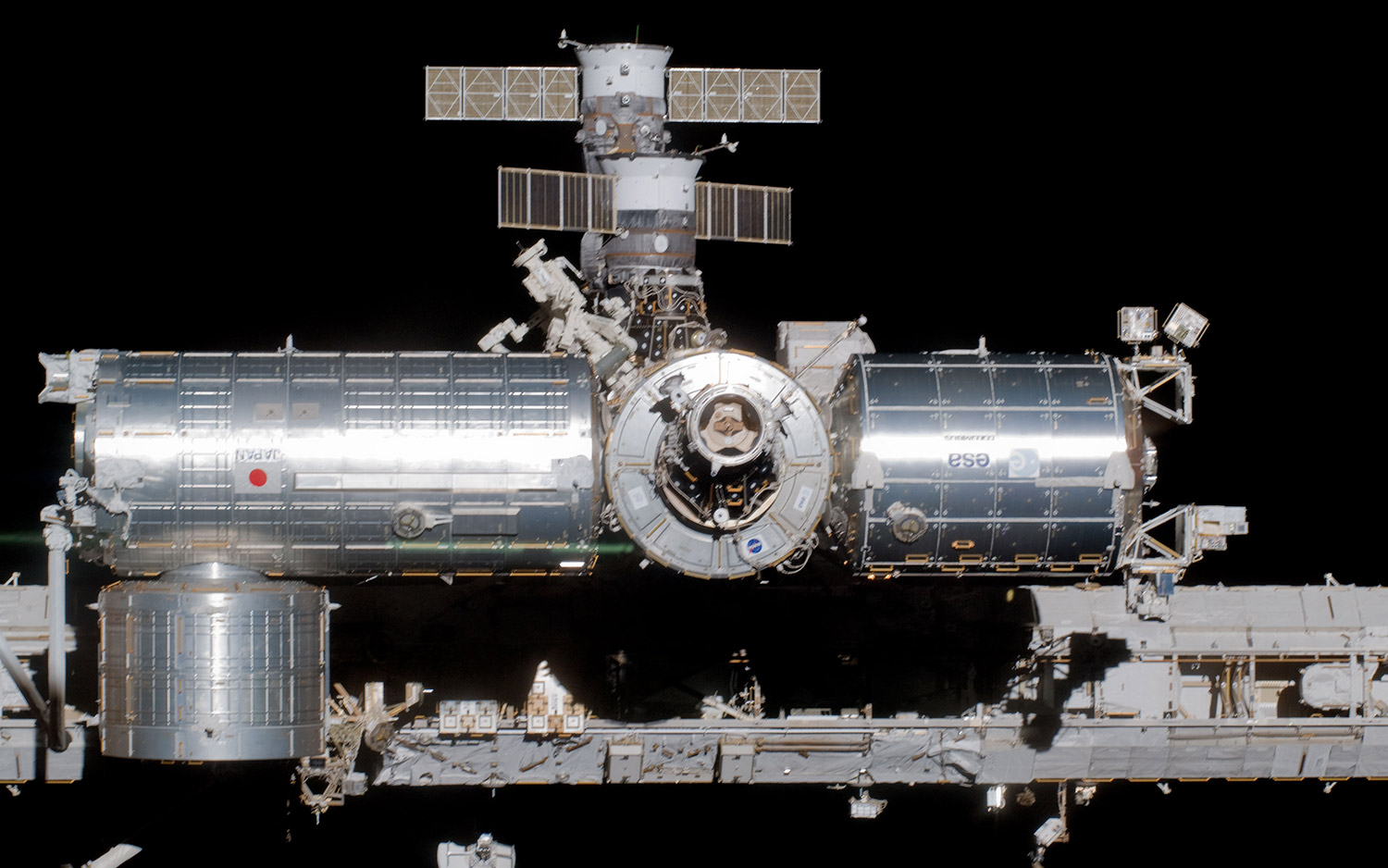

Related: International Space Station: A photo tour

"Sloppy management of the experiment has damaged the credibility of [our] research data and the scientific value of research as a whole," Hiroshi Sasaki, JAXA vice president, said in the Nov. 25 report from UPI, echoing the tone of an official statement from the space agency.

JAXA officials stated the situation made it impossible "to obtain reliable data worthy of publication" and that the study methodology "was a betrayal of the good intentions" of the research subjects. The space agency also apologized for the study. (Translation from Japanese was provided by Google.)

Furukawa last flew to the orbiting complex in 2011 for three months shortly after a deadly tsunami wiped out a great deal of Japan's infrastructure; he is slated for a second long-duration mission no earlier than 2023.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The research scandal comes at a time when JAXA, which holds nearly 13% of ISS crew time and research, is increasing its future collaborations with NASA in human spaceflight. (Japan's major space station contribution is the Kibo laboratory, along with a robotic arm and other hardware.)

As part of a larger U.S. international trade agreement announced in May, Japanese astronauts have been promised seats on Artemis missions to the moon and potentially a coveted landing mission spot, per comments from U.S. President Joe Biden and Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida at the time.

Furukawa's controversial study was meant to examine 42 people working in a closed environment for two weeks in a facility northeast of Tokyo, to "assess their stress levels and mental well-being," Japan Today reported. (Analog studies like this are normal practice in space research, allowing for a wider range of participants than the 500 or so professional astronauts who have been to space.)

The experiments took place in several rounds between 2016 and 2017, and no scientific journal results were produced after the study was halted in 2019.

The Japanese language investigation report from JAXA says "non-existent data was created" in at least five interviews associated with the study, a situation uncovered after an independent evaluator couldn't confirm a selection of the purported interviews had existed or had been recorded. (Translation provided by Reverso.)

"The creation of non-existent data undermines the credibility of the research content, and it was judged that it was an act that could be regarded as 'fabrication' from the perspective of researchers in general and society," officials wrote.

Investigators found rewritten and "falsified" research data that "compromised" experiment reliability, along with issues of scientific validity, data collection and data management, according to the report.

Study managers also failed to solicit informed consent of at least some participants, the report states — a major breach of basic research ethics in jurisdictions both Japan and the United States.

Informed consent ensures subjects know why they are participating in a study, how their data will be used, how their privacy will be protected and what countermeasures are available in case of mental or physical issues associated with participation, among other safeguards.

JAXA officials said the agency would report the results to two ministers (government department heads) responsible for health and education, adding the agency is looking at what caused these issues to "consider measures to prevent recurrence."

Elizabeth Howell is the co-author of "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022; with Canadian astronaut Dave Williams), a book about space medicine. Follow her on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.