Journey to JAXA: Why I skipped Mount Fuji and went straight to the Japanese space agency

To this day, I regret not trying the Space Curry.

There's this one particular image of Mount Fuji that has come to dominate social media feeds in recent months. You've probably seen it. Japan's hulking, slightly snow-capped volcano rises from behind the red, white and blue signage of a Lawson convenience store. Two Japanese icons, juxtaposed in the one image.

As striking as the scene is, it may come as a surprise that acquiring this specific image has become something of a bucket list item for many tourists. In a scramble that rivals the famous Shibuya crossing, amateur photographers and trained Instagram boyfriends have crowded the street and sidewalk in front of the Lawson store day after day, hoping to get the perfect shot.

A post shared by Peter Yan (@yantastic)

A photo posted by on

The crowds have become so bad in the shadow of Fuji that the town decided to install a mesh black screen in front of the unassuming Lawson. Of course, within days, people had poked holes in it to slip their cameras through. The overcrowding of famous landmarks, like Kyoto's famous Gion district, and a less-than-subtle disrespect for the country’s culture has been feeding the slightest hint of bitterness towards unruly tourists. And there are so many tourists. Including me.

Related: 'Absolutely gutted': How a jammed door is locking astronomers out of the X-ray universe

When I visited, just after the cherry blossoms peaked, we were everywhere: One American couple in a famous ramen spot caused a stir because they couldn’t figure out how to use the ordering machine. They claimed they paid (they did not pay), then loudly demanded a refund. The nasally Australia "naur thanks, mate" was a common refrain I heard at the 7/11 counter and, at Sensoji temple, you rubbed shoulders — quite literally — with the heaving crowds. I can tell you where there were very few crowds though: The 10:56 a.m. train from Machida Station to Fuchinobe station on a dreary May morning.

I can tell you this because, though I was clearly contributing to the overtourism conundrum, my mission in Japan wasn't to get the Instagram-worthy Fuji shot, traipse around the Imperial Palace or sample the retro video games on offer in Akihabara. Nope, I scooted myself halfway across the world to visit what Tripadvisor suggests is the 12th best thing to do in the quiet suburban town of Sagamihara: Go to space. Sort of.

Welcome to JAXA

As soon as I exit Fuchinobe Station, I'm confronted with a giant billboard featuring images of a spacecraft departing Earth. This was a clue: Just 15 minutes from the station lies the main campus of Institute of Space and Astronautical Science (ISAS), an arm of the Japan Space Exploration Agency (JAXA). It's not space, but it's about as close as you'll get in suburban Tokyo.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As I got closer to JAXA's front gate, I began to experience a peculiar sensation. I'd never been here before, but it felt like I was about to visit an old friend.

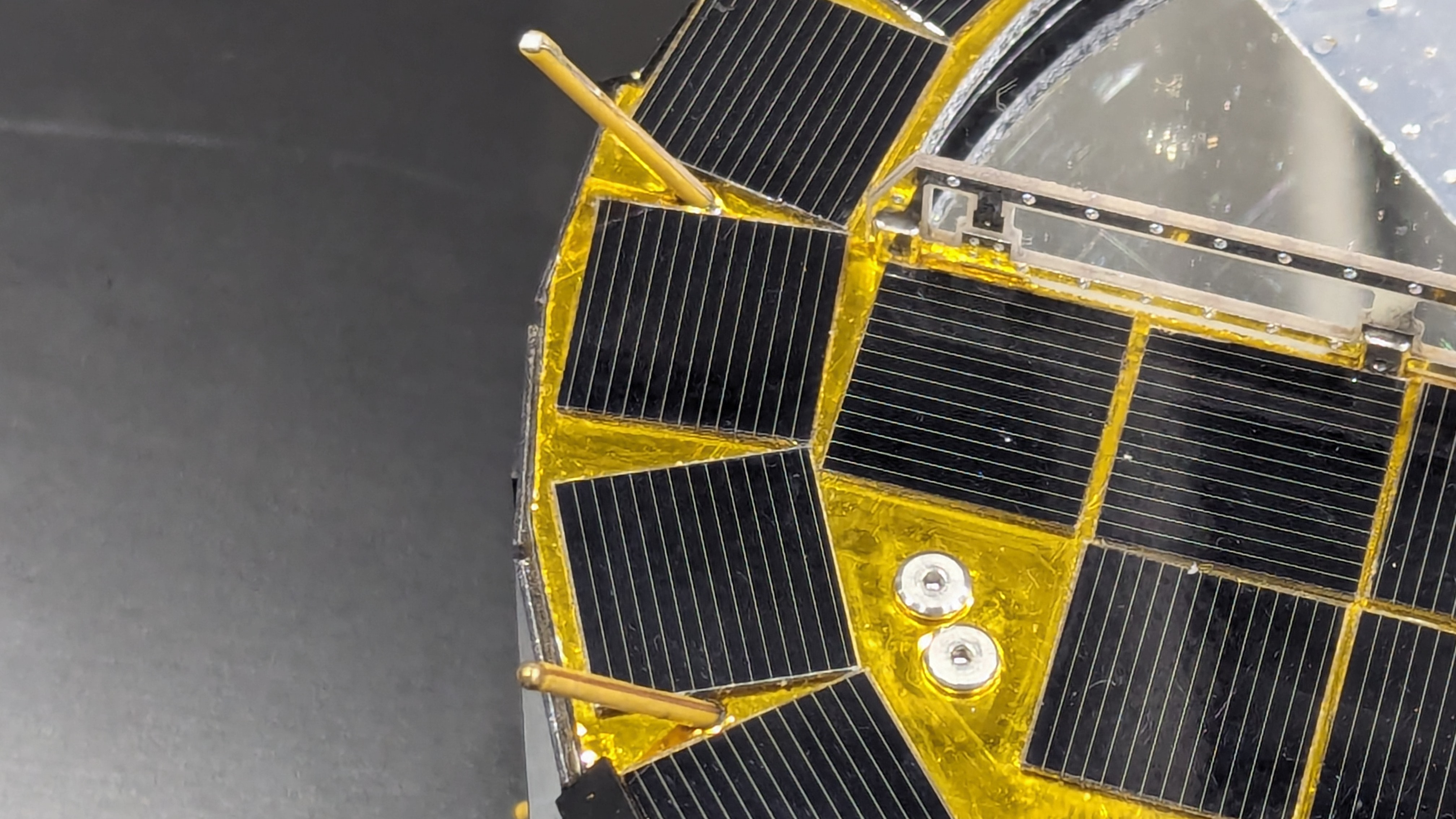

I've been writing about JAXA's considerable exploits for more than five years. During the Hayabusa2 sample return mission, which delivered samples from the asteroid Ryugu back to Earth in late 2020, I interviewed many of the scientists stationed in the Australian outback town of Woomera and, earlier this year, I tapped them again as they prepared to land the SLIM spacecraft on the Moon – a feat they achieved in February, though the probe landed upside down.

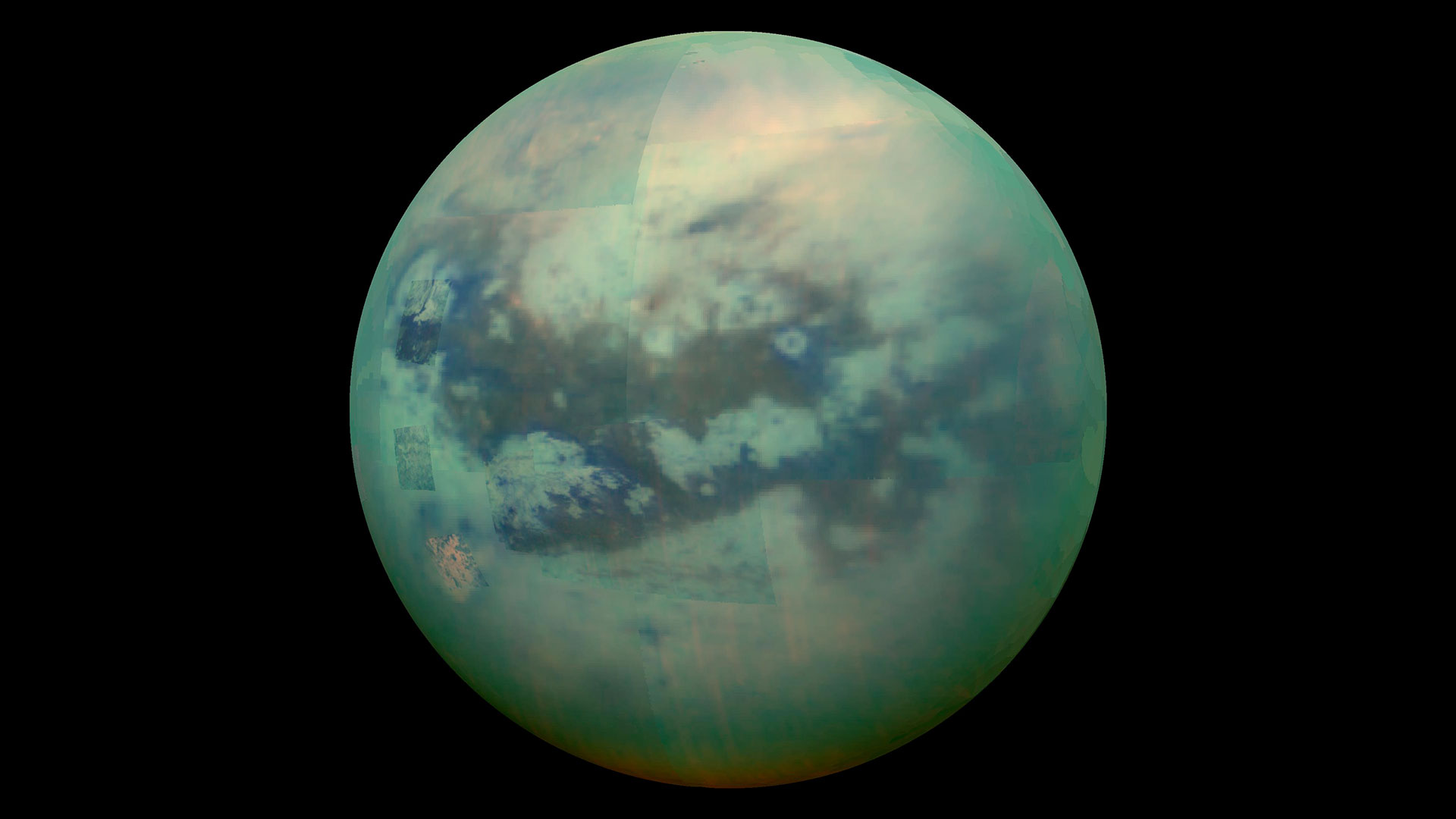

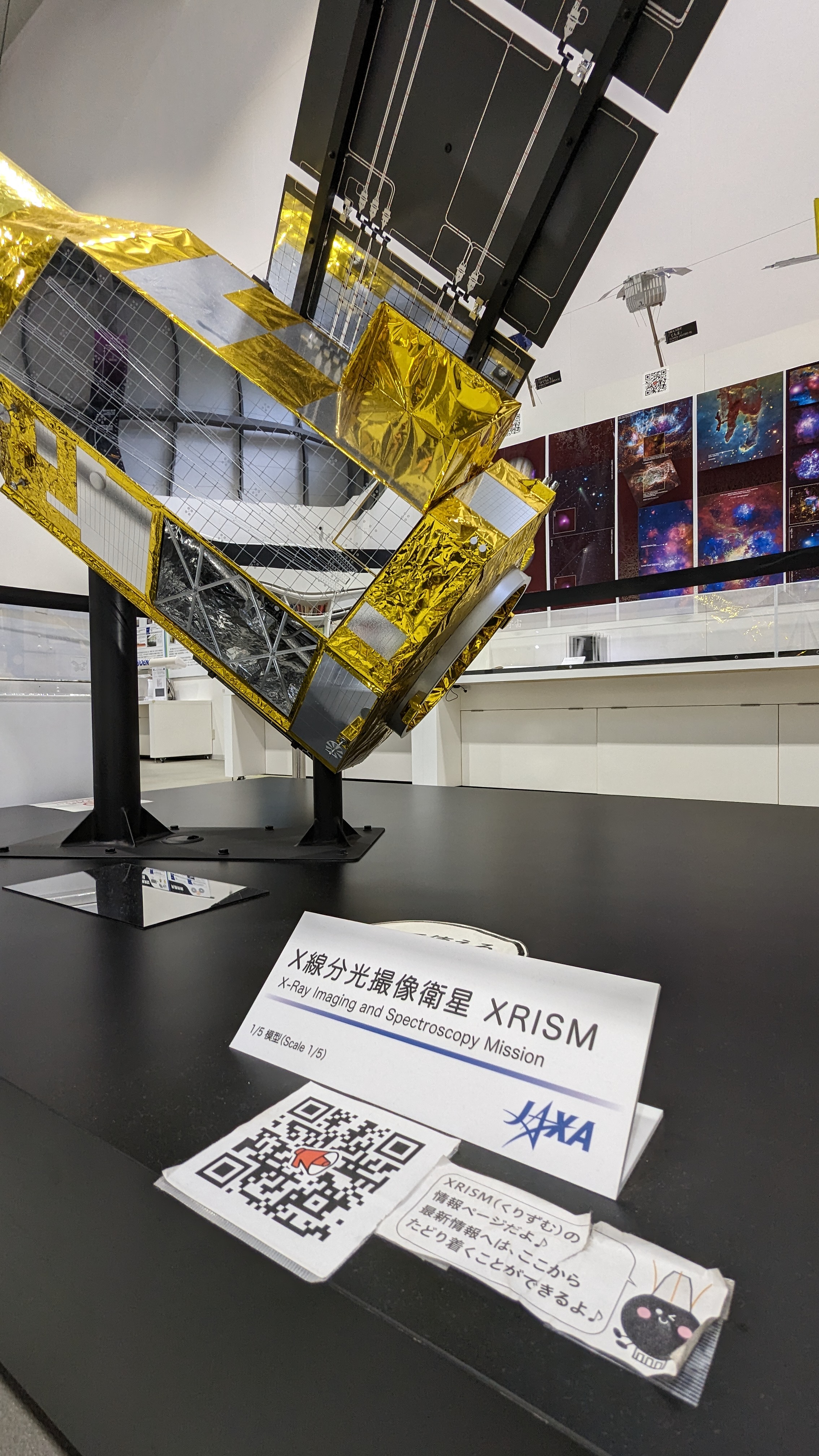

On this trip, I was focused on two things: the XRISM space telescope, which promises to unveil riveting corners of the universe to us via X-ray astronomy, and the ISAS curation facility, where asteroid bits and bobs are plucked and prodded until a breathtaking result reveals itself. I was looking for Hiroya Yamaguchi, an associate professor at Japan's Institute of Space and Astronautical Science working on XRISM, and Tomohiro Usui, who manages that very curation facility. Elizabeth Tasker, an associate professor at JAXA and member of the outreach team, was my chaperone.

I didn't quite know what to expect. I've mostly experienced the idea of a "space agency" through pop culture, film and TV, alongside the live feeds of Mission Control during daring missions to the moon, Mars and beyond.

My first destination was the main building — it wasn't anything like my imagination. A brutalist, utilitarian frontage outside. A series of offices line long hallways with beige linoleum floors and planetary science posters dotting the walls inside. This is where the magic happens, so to speak — in rooms where the vibe is utilitarian, dimly lit and a little sterile.

Just around the corner from the main building is where the action is: The curation facility.

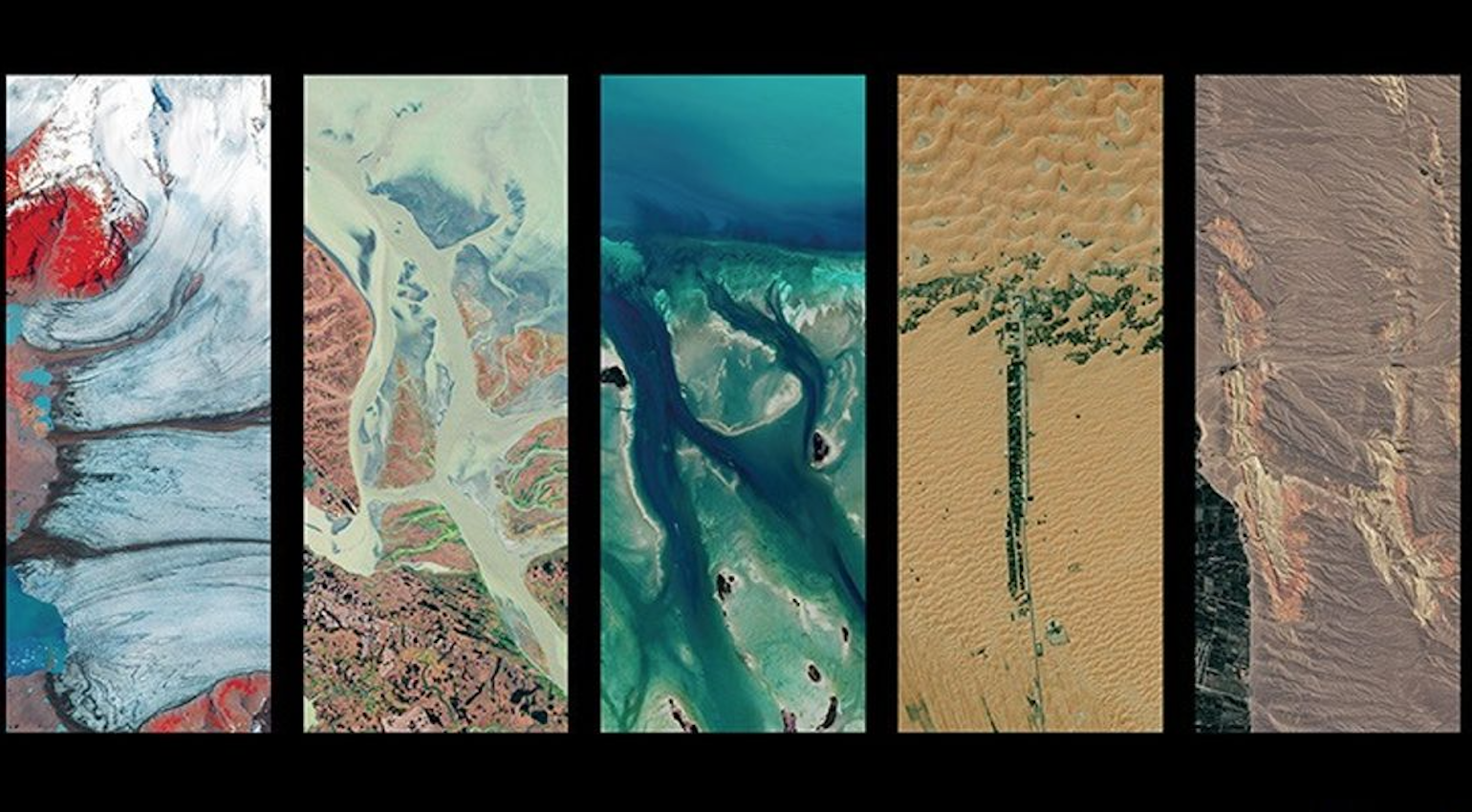

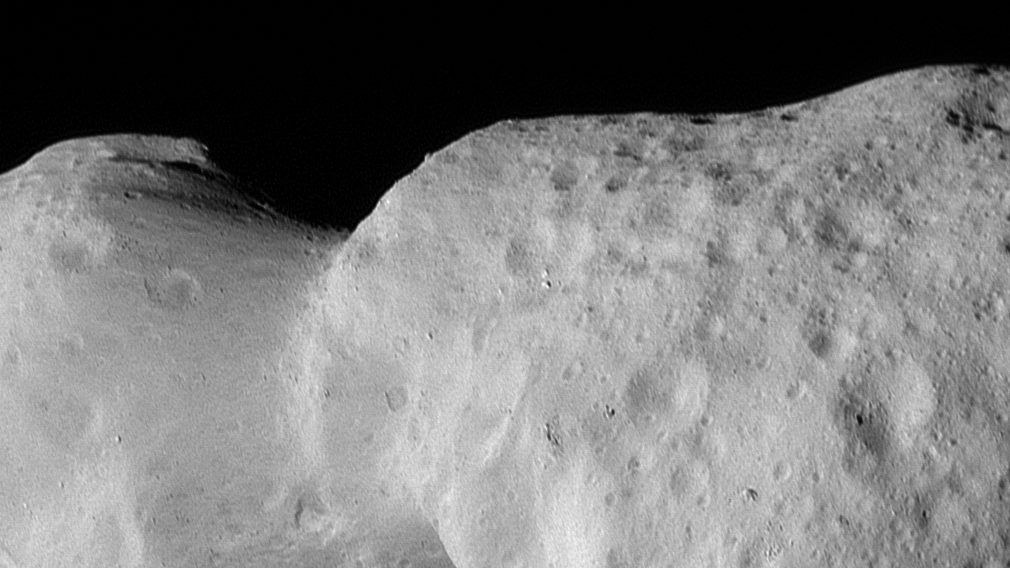

This facility was purpose-built for JAXA's asteroid sample return missions. The first of these missions, Hayabusa, suffered a number of setbacks during its journey, but JAXA was able to return the designated spacecraft to Earth with a miniscule amount of material from the bean-shaped asteroid Itokawa in 2010. Hayabusa2, its successor, was far more successful, delivering five grams of sample from the asteroid Ryugu a decade later.

On the day of my visit, Usui regales me with the story of lifting the lid on the latter sample return capsule for the first time, and reminisces about each checkpoint the grains of asteroid met throughout the facility. In front of us, beyond a window, I can see JAXA scientists moving around the clean rooms, clad in all white coats, double-gloved, and with only a slither of their faces showing. Every metal surface is pristine, with not a hint of dust.

This extreme cleanliness is a prerequisite. Of course, that means I can't just duck through an open door and sneak in for a closer look. Usui explains the clean rooms have to be kept at a constant 22 degrees Celsius (71.6 degrees Fahrenheit) and that each cubic foot of space must have less than 1,000 particles of dust. He also notes that samples from Bennu, the asteroid visited by NASA's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft, will be studied here by JAXA scientists in a new clean room, specifically designed for those samples.

"We learnt a lot from curation of Ryugu," Usui tells me. The new clean room has the same bells and whistles that JAXA had for cracking open the Hayabusa2 capsule — except this time, the samples aren't coming directly from an asteroid to Earth. NASA has already cracked open their sample capsule and plucked out pieces of Bennu to hand over, storing them in nitrogen-filled capsules for future analysis. They'll arrive at the facility sometime this summer.

The lessons learned here will then be applied to JAXA's next sample return attempt, the Martian Moons eXploration (MMX) mission. It aims to land a probe on the surface of the potato-shaped Phobos, one of Mars' two moons. Launch was expected in 2024, but the mission has been delayed to 2026 due to problems with the launch vehicle.

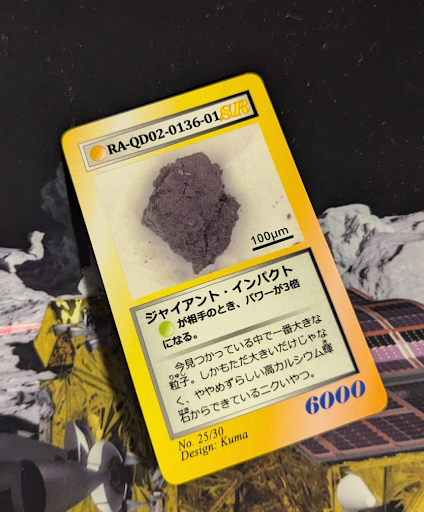

In typical Japanese fashion, I also get my own Curation Facility collectible through a lucky dip: A card from JAXA's in-house asteroid grain trading card game, RA-QD02-0136-01. It contains a photo of an extremely small grain nabbed from Itokawa and, Usui assures me, it is "an extremely rare card." I take his word for it.

To be frank, I'm still kind of blown away by just standing in the facility. The fact that tiny pieces of rock from an asteroid 4.6 billion years old were first analyzed in these very rooms is difficult to comprehend. Human brains are not built to understand time on that kind of scale. My brain is operating on the length of a day and, as we exit, it's telling me that it's lunch time.

Space cafe

The cafeteria, I find, is selling a Space Curry.

The marketing for the dish features an image of the typical Japanese curry over rice — there’s no sprinkling of asteroid dust or anything, to my dismay. It seems to be a regular curry, except for the fact the curry's image on the poster is backed by a starry sky. I opt for the noodles and buy a cold milk from the vending machine nearby. To this day, I regret not trying the Space Curry.

Just across the yard is the Communication Hall of Space Science and Exploration, where most tourists will spend their time. The building, which is essentially a visitor center crossed with a museum, was nearly empty when I got there, save for an older Japanese couple and a tour guide. Out front, two full-scale model M-class rockets, once used to lift Hayabusa and other spacecraft to orbit and beyond, rest on their sides.

Indoors is where the stargazers really get to nerd out, though, with scale replicas of many different JAXA spacecraft — Hayabusa2 and its hopping robots, as well as SLIM, the agency's moon lander that touched down (on its nose) on Jan. 26. At the back of the Hall, I come to the final stop on the whirlwind tour. This is where the pièce de résistance, the center's Mona Lisa, resides: grains obtained from Ryugu. This is my Mount Fuji moment. But, Tasker warns, there are no photos allowed in here.

The overtourism issue is becoming a real conundrum for Japan, especially as winter gives way to spring and the cherry blossoms bloom. It's expected the country will easily surpass its record annual tourist numbers this year. As TikTok and Instagram send people searching for unnaturally filtered views of empty, peaceful and exotic locales they've scrolled past on their phones, it's getting harder to recreate those already unattainable views.

This isn't the case out in Sagamihara. There's a tranquility that touches on an underlying Instagram-can't-capture-it experience (even if, like me, you find yourself visiting as a thunderstorm rolls through). JAXA isn't particularly adept at showmanship and bravado, and it often wears humility like armor, but it's exactly for these reasons that its little corner of Tokyo remains peaceful. Mount Fuji, a photogenic and remarkable natural wonder, is awash with travelers. But 4.6 billion-year-old pieces of an asteroid, though perhaps less photogenic, are tucked away at the back of a hall. This sticks with me.

Later that evening, I find myself wandering the streets of Shinjuku — awash in the neon lights and listening to the radio of familiar accents. I stop down one famous street to snap a photo of Godzilla's head emerging from behind a building, the monster's face illuminated in cobalt. I was transfixed for a moment, reminiscing about Godzilla Minus One and looking at the cloudy skies behind. I wish I could tell you I had some sort of revelation, some sort of epiphany about our desires to explore the universe.

A young man taps me on the shoulder.

"Sorry, just trying to take a picture,'' he says in perfect English, gesturing at his smartphone and his girlfriend standing just behind me. It was one of the trained boyfriends.

"Ah, sure, sorry," I say, and move out of the way.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jackson Ryan is a science journalist hailing from Adelaide, Australia, with a focus on longform and narrative non-fiction work. He currently serves as the President of the Science Journalists Association of Australia. Between 2018 and 2023, he was the science editor at CNET. In 2022, he won the Eureka Prize for Science Journalism, which Aussies dub the "Science Oscars." Before all that, he got his doctorate in molecular biology and once hosted a kids TV show on the Disney Channel, called "GameFest." (Good luck finding it.) He lives with a collection of more than 70 Christmas sweaters and zero pets, the latter of which he hopes to rectify one day.