See Jupiter and Saturn at their brightest this week

Planets are very much in the fore these days, especially with the two largest — Jupiter and Saturn — now putting on a show as prominent evening luminaries. This week, both planets appear at their very best, with Jupiter having just arrived at opposition this past Tuesday (July 14) and Saturn to reach its own opposition on Monday (July 20).

On Dec. 21, these two planets will be in conjunction — meaning they'll share the same celestial longitude while making a close approach in the night sky — for the first time since the year 2000. It takes Saturn almost 30 years to make one trip around the sun, while it only takes Jupiter about 12 years to complete one solar revolution. As a result, Jupiter appears to overhaul Saturn at intervals of roughly 20 years.

Let's check out both of these giant worlds, which will remain prominent objects in our evening sky through the balance of this year. Saturn and Jupiter provide telescope users with a feast of features. Saturn of course has its splendid ring system and Jupiter can boast a restless atmosphere and retinue of bright moons.

Related: The brightest planets in July's night sky

Jupiter

As we just noted, Jupiter arrived at that point in the sky directly opposite to the sun, called "opposition," on Tuesday (July 14). If the planets' paths around the sun were true circles, this would also coincide with Earth's closest approach to Jupiter, 384.8 million miles (619.1 million kilometers). However, because the planets' orbits are slightly oblong, that actually occurred the following day, on Wednesday (July 15).

Opposition occurs when the Earth, moving faster in its orbit than Jupiter, overtakes it. (This is true for any of the outer planets.) From now on, we'll leave Jupiter behind, catching up with the planet again on Aug. 19, 2021. Jupiter is also currently moving closer to the sun in its own elliptical path and will reach its closest point to the sun, 460 million miles (740 million km), at its perihelion point on Jan. 20, 2023.

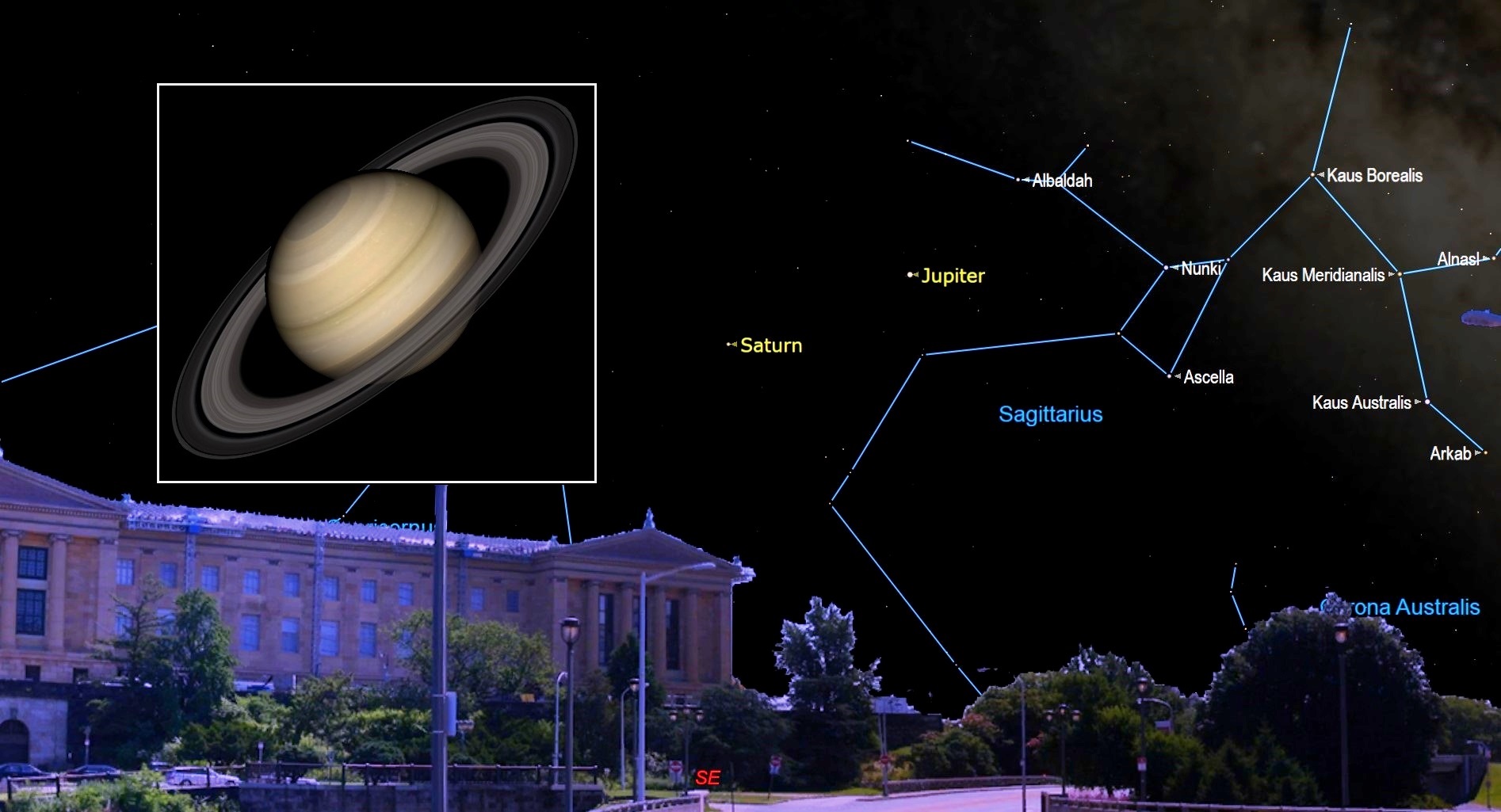

Jupiter, the largest planet in the solar system, shines as a brilliant silvery "star" to the upper left of the famous Teapot asterism of Sagittarius, low in the east-southeast sky as dusk arrives and will now appear to climb higher in the evening sky in the weeks to come.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Currently, this giant planet is ready for telescopic observing by 10:45 p.m. local time, when it will stand roughly one-quarter of the way up from the horizon to the point directly overhead, called the zenith. It reaches its highest position in the south around 12:30 a.m. and is heading toward its setting in the west-southwest during dawn.

With a diameter of 88,800 miles (143,000 km), Jupiter is a colossal ball of hydrogen and helium without a solid surface. It has a rocky core encased in a thick mantle of metallic hydrogen enveloped in a massive atmospheric cloak of multi-colored clouds of ammonium hydrosulphide.

In a strange sense, Jupiter might even be referred to as a "stillborn star," for it has the makings (mostly hydrogen) if not the mass of a stellar body. Its relative smallness, however, prevents the initiation of the nuclear processes that could have turned it into a full-fledged star. Had this been the case, we would have the distinction of living within a binary star system.

Jupiter is the most consistently interesting object in the solar system after the moon and the sun and has always held a special place in the hearts of telescope viewers.

The smallest telescope — even steadily held 7-power binoculars — show Jupiter as a tiny disc, while a medium-size telescope reveals numerous dark belts, light zones and a wealth of festoons, garlands, ovals and other features extending here and there.

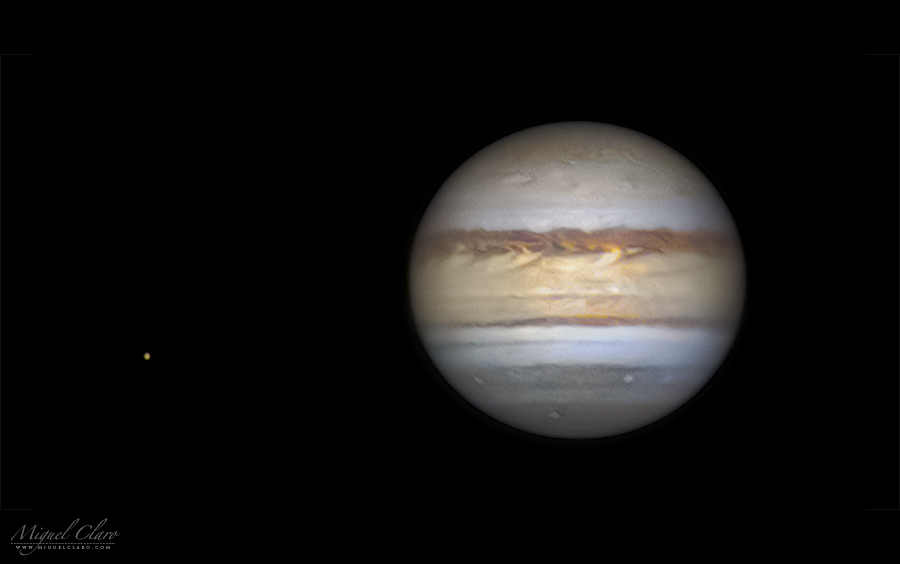

But Jupiter's greatest telescopic treasure are its four Galilean satellites that run a merry chase with each other around the planet (in all Jupiter has 79 confirmed moons), changing their respective positions from hour to hour and night to night.

Typically, at least two or three Galilean moons are visible at any given moment. The four — Io (I), Europa (II), Ganymede (III) and Callisto (IV), numbered by the order in which they were named — are all larger than Earth's moon. They can be followed for hours as they speed in front of Jupiter (throwing their shadows on the planet), vanish behind its giant disk or plunge into its shadow. They appear as tiny stars nearly in line and changing their places in the line as they revolve around the planet in orbits nearly edgewise to us.

On July 22, for example, we would see all four satellites on one side of Jupiter. Moving outward from Jupiter, they will also be, interestingly, in numerical order: Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto.

Saturn

Now is also the best time to observe the telescopic showpiece of the night sky, the ringed planet Saturn. Saturn, like Jupiter, also currently lies in the constellation of Sagittarius, the archer, adjacent to the border of another zodiacal constellation, Capricornus, the sea goat.

On Monday night (July 20) Saturn arrives at its own opposition, when it too will lie on the opposite side of the sky from the sun. This is also when its apparent size is greatest, and it puts on an all-night performance with greatest gleam. It is now shining at magnitude +0.1, just a trifle dimmer than Vega, the brightest star of the Summer Triangle, yet still only about 8% as bright as nearby Jupiter. (Magnitude is a measure of brightness used by astronomers, with smaller numbers indicating brighter objects.)

In ancient days, before we had knowledge of the more distant planets Uranus and Neptune, Saturn was presumed to be the farthest and slowest-moving known planet. In mythology, Saturn closely resembled the Greek god Cronus, but he's more usually recognized as the Roman god of agriculture. The name is related to both the noun satus (seed corn) and the verb serere (to sow).

So, why would the planet Saturn be linked to agriculture? Perhaps a clue can be found from the ancient Assyrians who referred to Saturn as lubadsagush, which translated meant "oldest of the old sheep." Possibly this name was applied because Saturn seems to move so very slowly among the stars; it may have also reminded skywatchers of the slow gait of plowing oxen or cattle.

Seen with only the naked eye, Saturn now appears a very bright yellow-white star shining with a steady glow, but the ring system that makes it both beautiful and spectacular cannot be seen. Any small telescope magnifying more than 30 power, however, will clearly show the rings. They consist of countless billions of particles — largely water ice — that range in size from microscopic specks to flying mountains miles across. Each particle revolves around Saturn in its own orbit. They are likely the pulverized icy fragments of a satellite that probably ventured too close to Saturn and was torn apart by tidal forces.

Currently, the rings are dramatically tipped nearly 22 degrees to our line of sight. When Galileo Galilei's crude, imperfect "optick tube" revealed Saturn as having an odd pair of appendages or smaller companion bodies on either side, leaving him completely baffled. He announced this discovery in 1610 with an anagram written in Latin. The jumbled letters could be transposed to read: Altissimum planetam tergeminum observavi ("I have observed the highest planet to be triple").

Later, when the rings turned edgewise to Earth and the two companions disappeared, Galileo invoked an ancient myth when he wrote, "Has Saturn swallowed his children?" It was not until March 25, 1655 that a Dutch mathematician, Christiaan Huygens, utilized a much better telescope, and saw the rings for what they really were. Huygens also discovered Saturn's largest moon, Titan, larger than either Mercury or our moon. It is but one of 82 known satellites circling Saturn.

The theoretical construction of Saturn — 74,900 miles (120,500 km) wide — resembles that of Jupiter; it is either all gas, or has a small dense center surrounded by a layer of liquid and a deep atmosphere. And since its specific gravity is less than that of water, Saturn would float — if you could find an ocean large enough to drop it in!

Celestial summit meeting

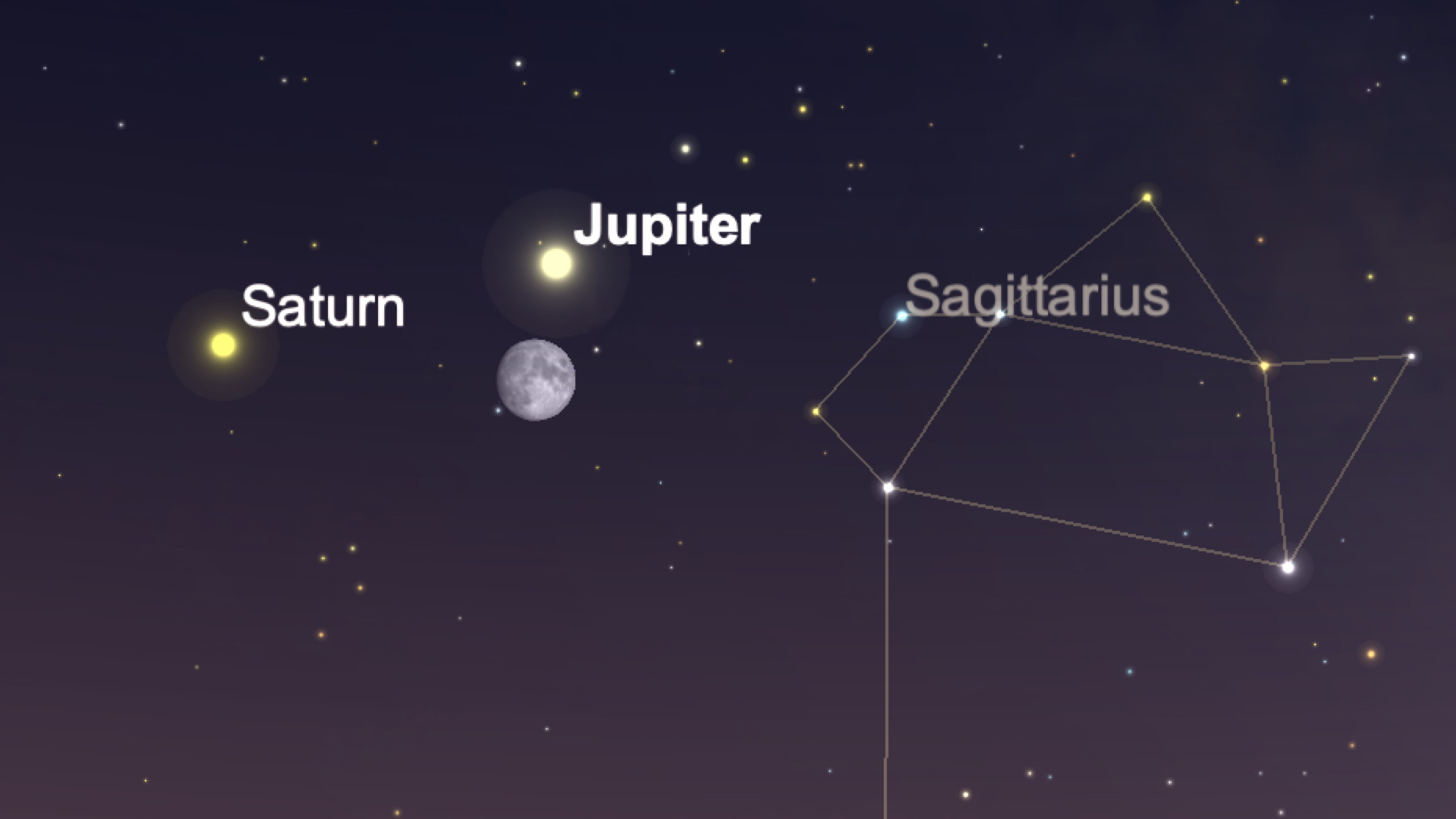

One of my astronomy mentors, Kenneth L. Franklin (1923-2007), former chief astronomer at New York's Hayden Planetarium would periodically make reference to our "dynamic and ever-changing sky." Such an eloquent description certainly will fit the evening sky on Aug. 1, as we'll have a celestial summit meeting of sorts taking place in southeast sky at nightfall. A waxing gibbous moon will be accompanied by Jupiter, hovering above it, while Saturn will be well off to the moon's left.

Related: Moon phases

If you have a telescope, why not invite some friends and neighbors over that evening? First give them a look at the moon. Then, without revealing what it is, train your scope on that bright yellow-white "star" to its left and tell them to take a look. You'll likely hear exclamations of delight, especially if they're getting their first look at the ringed planet!

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.