Jupiter's ocean moon Europa may spout water plumes from its icy crust

The Jupiter moon Europa may cough water into space from small pockets in its icy crust, a new study suggests.

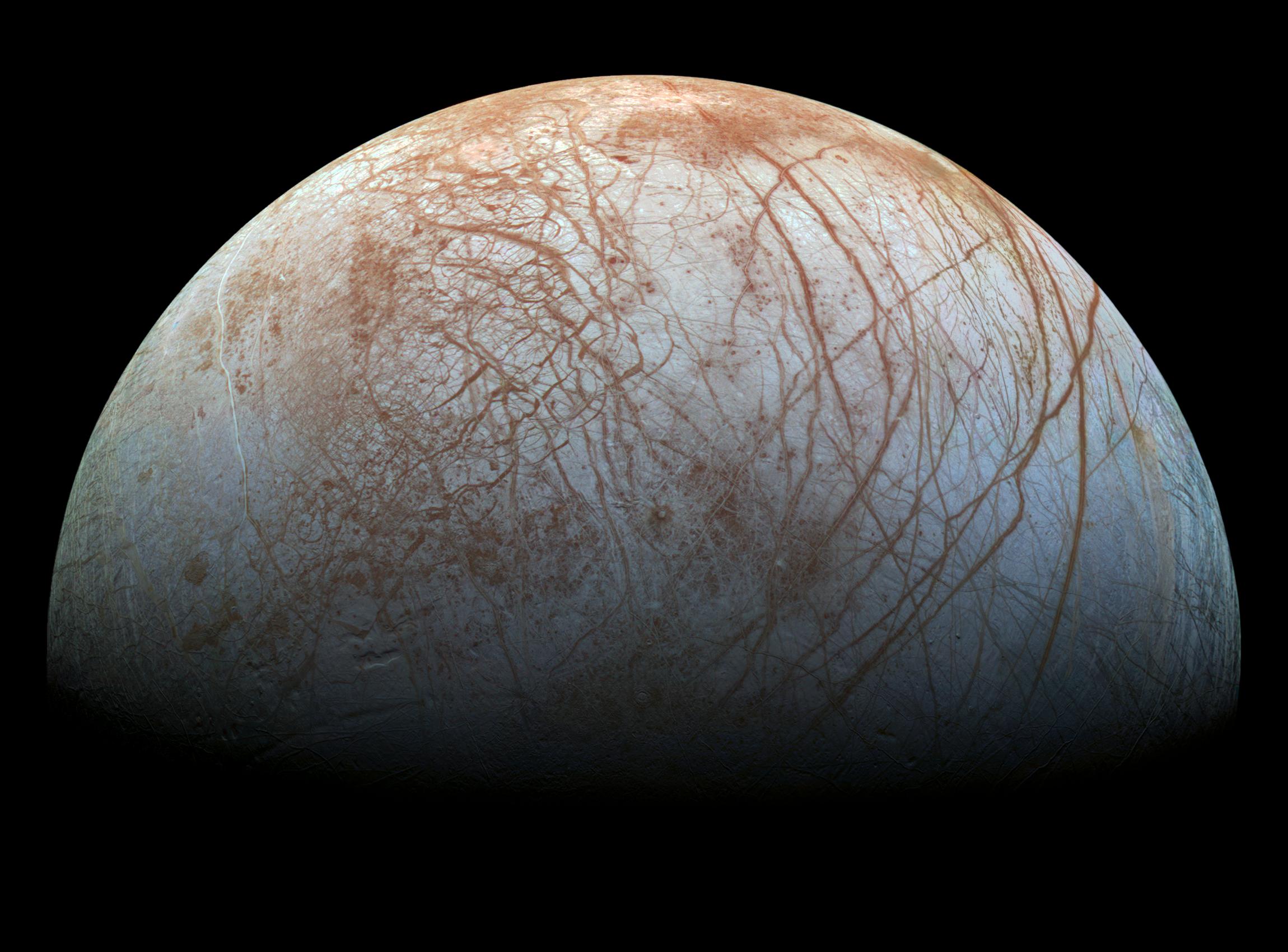

Europa, one of Jupiter's four big Galilean moons, harbors a huge ocean of salty water beneath its ice shell and is widely regarded as one of the solar system's best bets to host alien life.

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and other instruments have spotted evidence of sporadic plumes of water vapor that rise perhaps 120 miles (200 kilometers) above Europa's frigid surface. This water may be coming from the buried ocean, raising the exciting possibility that a spacecraft could sample this potentially life-supporting environment without even touching down on the moon.

Photos: Europa, mysterious icy moon of Jupiter

Such sampling work might be done by NASA's Europa Clipper probe, which is scheduled to launch in the mid-2020s. Clipper will orbit Jupiter and study Europa during dozens of close flybys, characterizing the ocean and the ice shell and scouting out possible touchdown sites for a future life-hunting lander. (Clipper team members have stressed that the probe will likely have to get lucky to pull off a sampling run, however, given that Europa's plume activity isn't well characterized and appears to be sporadic.)

Those apparent big plumes may have smaller cousins, which are emanating from a source just below the surface, according to the new research.

The scientists, led by Gregor Steinbrügge of Stanford University and Joana Voigt of the University of Arizona, analyzed Europa's Manannán Crater, an 18-mile-wide (29 km) feature created by an impact tens of millions of years ago.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The heat generated by this impact doubtless melted a considerable portion of the nearby ice, and the researchers modeled what happened next. They found that some pockets of salty liquid brine likely survived for a spell after most of the meltwater had refrozen. In addition, the team determined that such pockets could move laterally through Europa's shell, by melting some of the adjacent ice.

The modeling work further suggested that such migration happened at Manannán: A pocket probably made its way to the crater's center and then began to freeze, causing a pressure buildup that eventually blasted out a roughly 1-mile-high (1.6 km) plume.

There is evidence that such a plume did actually exist — a spider-shaped feature at Manannán that was spotted by NASA's Galileo spacecraft, which studied the Jupiter system while orbiting the giant planet from 1995 to 2003. (The researchers worked this spidery imprint into their model.)

"Even though plumes generated by brine pocket migration would not provide direct insight into Europa's ocean, our findings suggest that Europa's ice shell itself is very dynamic," Voigt said in a statement.

"The work is exciting, because it supports the growing body of research showing there could be multiple kinds of plumes on Europa," Europa Clipper project scientist Robert Pappalardo, of NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in the same statement. "Understanding plumes and their possible sources strongly contributes to Europa Clipper's goal to investigate Europa's habitability."

The new study was published this month in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.