A huge asteroid crash permanently altered Jupiter's biggest moon Ganymede

The asteroid strike would have "completely removed the original surface" of Ganymede.

A colossal asteroid slammed into Jupiter's largest moon Ganymede with so much power it dramatically and permanently reoriented the moon roughly 4 billion years ago, new research suggests. Scientists say the pivotal impact also significantly influenced the geological and internal evolution of the moon, which is larger than Mercury.

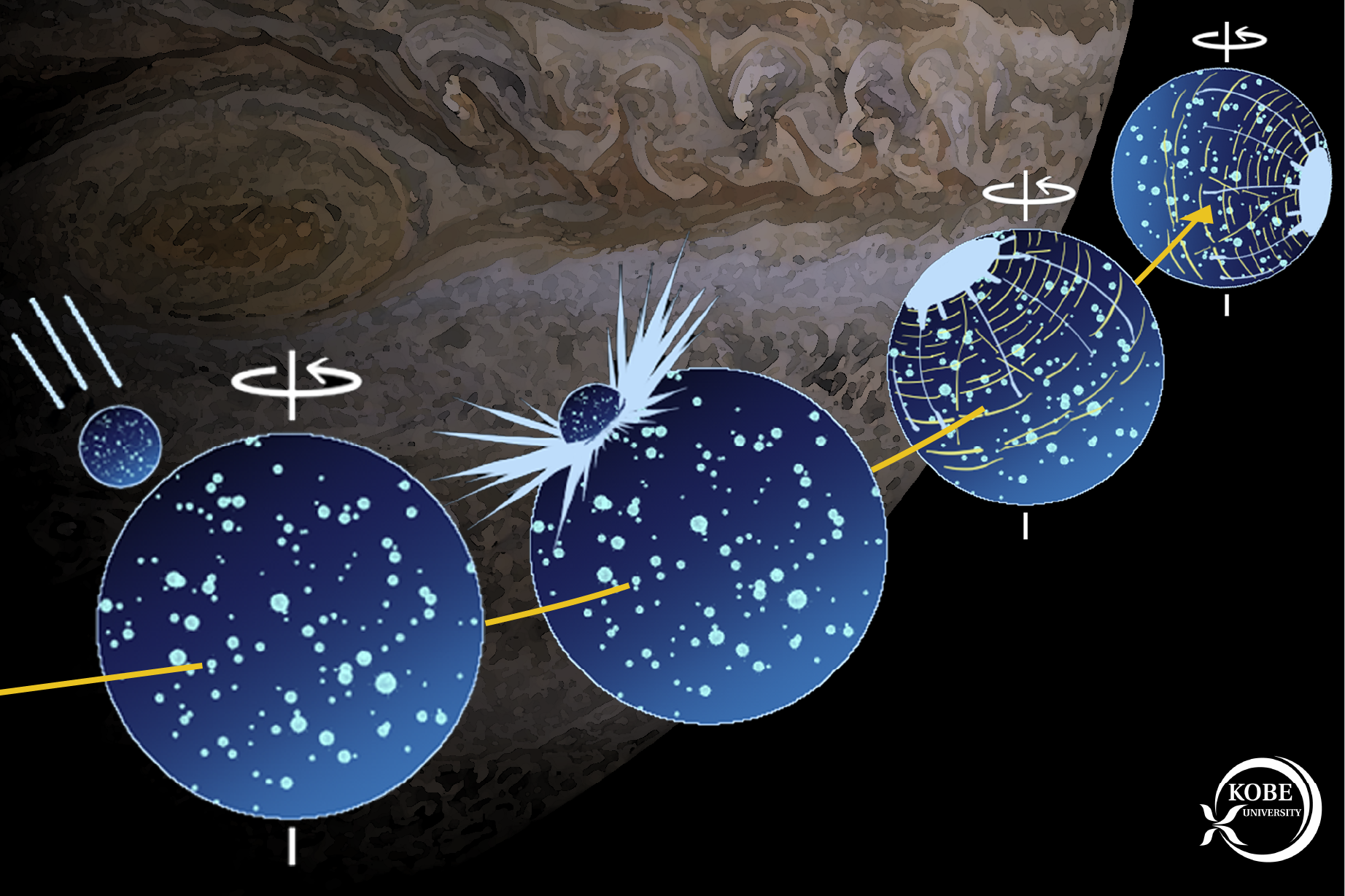

Computer simulations by planetary scientist Naoyuki Hirata of Japan's Kobe University predict the asteroid must have been about 186 miles (300 kilometers) wide, or 20 times bigger than the fateful one that wiped out the dinosaurs from the face of our planet about 66 million years ago.

Only an impact of this scale would be powerful enough to destabilize Ganymede and cause the tidally-locked moon to whirl on its axis, according to a study published by Hirata on Tuesday (Sept. 3) in the journal Scientific Reports.

"This is a neat attempt to rewind the clock via computer simulations, searching for an explanation for the distribution of scars across Ganymede," Leigh Fletcher, a planetary scientist at the University of Leicester in the U.K. who was not involved with the new study, told The Guardian.

Hirata estimates the consequential process unfolded over approximately 1,000 years following the asteroid impact. The space rock likely crashed into Ganymede at an angle of 60 to 90 degrees and produced a crater somewhere between 870 to 990 miles wide (1400 to 1600 km), the new study finds.

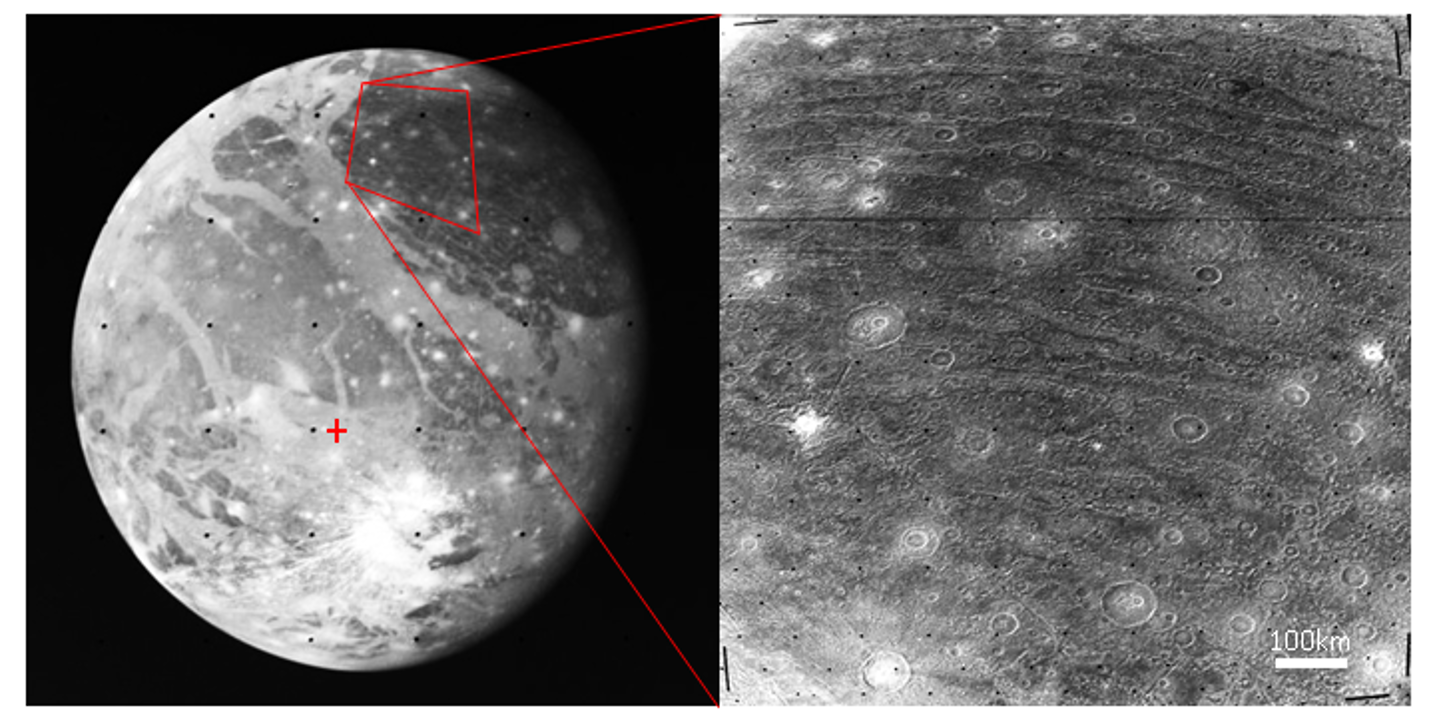

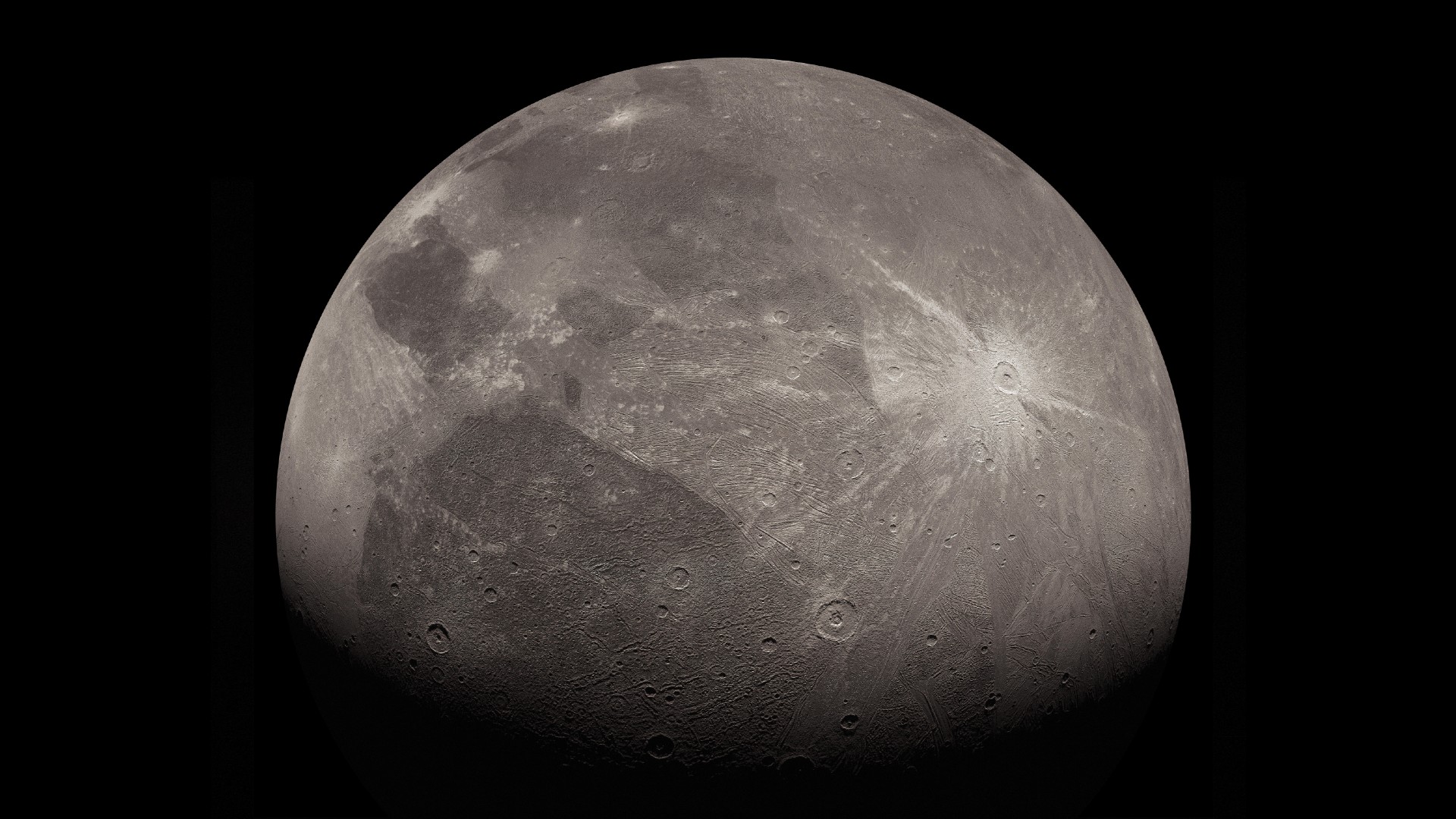

The evidence for Ganymede's reorientation is rooted in its surface, which is pockmarked with extensive furrows, or concentric rings of troughs thought to be fragmented remnants of bowl-shaped basins created by asteroid impacts. A fresh analysis of Ganymede's largest furrow system, which scars the moon just below its equator, suggests that the asteroid strike caused the moon to spin such that the impact crater faces away from Jupiter.

The asteroid strike would have "completely removed the original surface" of Ganymede, thanks to the crater reaching a whopping 25 percent of the moon's size, the researcher said in a recent statement. The impact would have significantly affected the moon's geology and interior, where scientists think a hidden saltwater ocean containing more water than all of Earth's oceans combined exists.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Although both Voyager spacecraft as well as the Galileo probe took images of Ganymede in the late 1900s, many areas of the moon have not yet been imaged with sufficient resolution, limiting scientists' understanding of its history and evolution. For instance, Ganymede's dramatic reorientation may have spurred fractures and other tectonic landforms across its surface that haven't been discovered yet, Hirata said.

Forthcoming images of Ganymede from the European Space Agency's JUICE spacecraft could reveal more about how the asteroid strike shaped the moon's evolution. JUICE pulled off difficult gravitational slingshots past our moon and Earth just last month, and is set to arrive at the Jupiter system in 2031.

Over the following 2.5 years, the solar-powered JUICE will orbit the gas giant while swinging past Ganymede, Europa and Callisto multiple times, cataloging their surface features as well as potential for habitability by flying within 120 to 620 miles (200 to 1,000 kilometers) of their surfaces.

JUICE will return to Ganymede in December 2034 for a dedicated nine-month study, which would mark the first time a spacecraft orbits a moon other than our own.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.