The photos from a historic flyby of our solar system's largest moon are starting to roll in.

On Monday (June 7), NASA's Juno probe zoomed within just 645 miles (1,038 kilometers) of Jupiter's enormous satellite Ganymede, which is bigger than the planet Mercury. It was the closest any probe had come to Ganymede since May 2000, when NASA's Galileo spacecraft got within about 620 miles (1,000 km) of the moon's icy surface.

It'll take some time to receive and process all the data from Monday's encounter, but we're already getting a taste: The first two photos from the flyby have come down to Earth, and NASA posted them online Tuesday (June 8).

Related: Photos of Ganymede, Jupiter's largest moon

One of the images, snapped by the JunoCam instrument, shows nearly an entire side of the crater-pocked Ganymede, which is thought to harbor a huge ocean of liquid water beneath its ice shell. (That ocean is likely sandwiched between two ice layers, however, so it's not as astrobiologically interesting as the subsurface seas of fellow Jupiter moon Europa and the Saturn satellite Enceladus. Those other buried oceans are in contact with their moons' rocky interiors, making a variety of complex chemical reactions possible, scientists say.)

The JunoCam photo, which has a resolution of about 0.6 miles (1 km) per pixel, was captured using the instrument's green filter. The image is black and white, but the mission team will be able to create a color portrait once the versions taken with JunoCam's red and blue filters come down, NASA officials said.

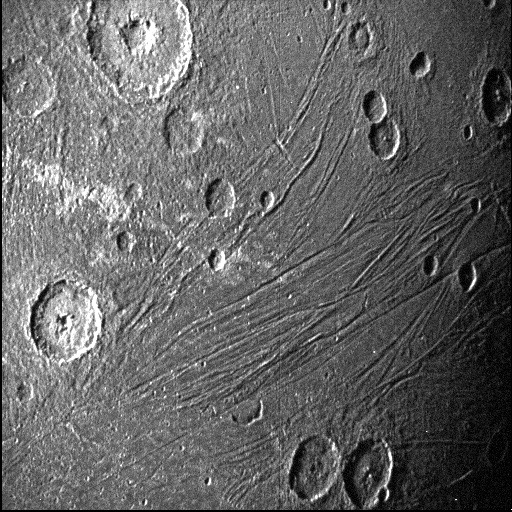

The second photo comes courtesy of the Stellar Reference Unit, a black-and-white camera that Juno uses for navigation. This image, which features a resolution of 0.37 miles to 0.56 miles (0.6 to 0.9 km) per pixel, shows the side of Ganymede opposite the sun, which is faintly illuminated by light bouncing off Jupiter.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The conditions in which we collected the dark side image of Ganymede were ideal for a low-light camera like our Stellar Reference Unit," Heidi Becker, Juno's radiation-monitoring lead at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, said in a statement.

"So this is a different part of the surface than seen by JunoCam in direct sunlight," Becker said. "It will be fun to see what the two teams can piece together."

Juno launched in August 2011 and arrived at Jupiter in July 2016. The solar-powered probe is studying Jupiter's composition, interior structure and magnetic and gravitational fields, gathering data that should help scientists better understand how Jupiter and our solar system formed and evolved.

Juno occasionally turns its sharp eyes toward other objects in the Jovian system — like the 3,273-mile-wide (5,268 km) Ganymede. Observations made during Monday's flyby could reveal key insights about the moon's composition, ice shell and radiation environment, among other characteristics, NASA officials said.

Such data could help inform and guide future missions to the Jupiter system, including Europe's Jupiter Icy Moons Explorer (JUICE) spacecraft, which is scheduled to launch in 2022 to study Ganymede and fellow Galilean moons Europa and Callisto up close.

Mike Wall is the author of "Out There" (Grand Central Publishing, 2018; illustrated by Karl Tate), a book about the search for alien life. Follow him on Twitter @michaeldwall. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.