A change in Jupiter's orbit could make Earth even friendlier to life

The surface of our planet could be even more hospitable to life if the gas giant shifted its orbit.

A shift in Jupiter's orbit could make Earth's surface even more hospitable to life than it already is, new research suggests.

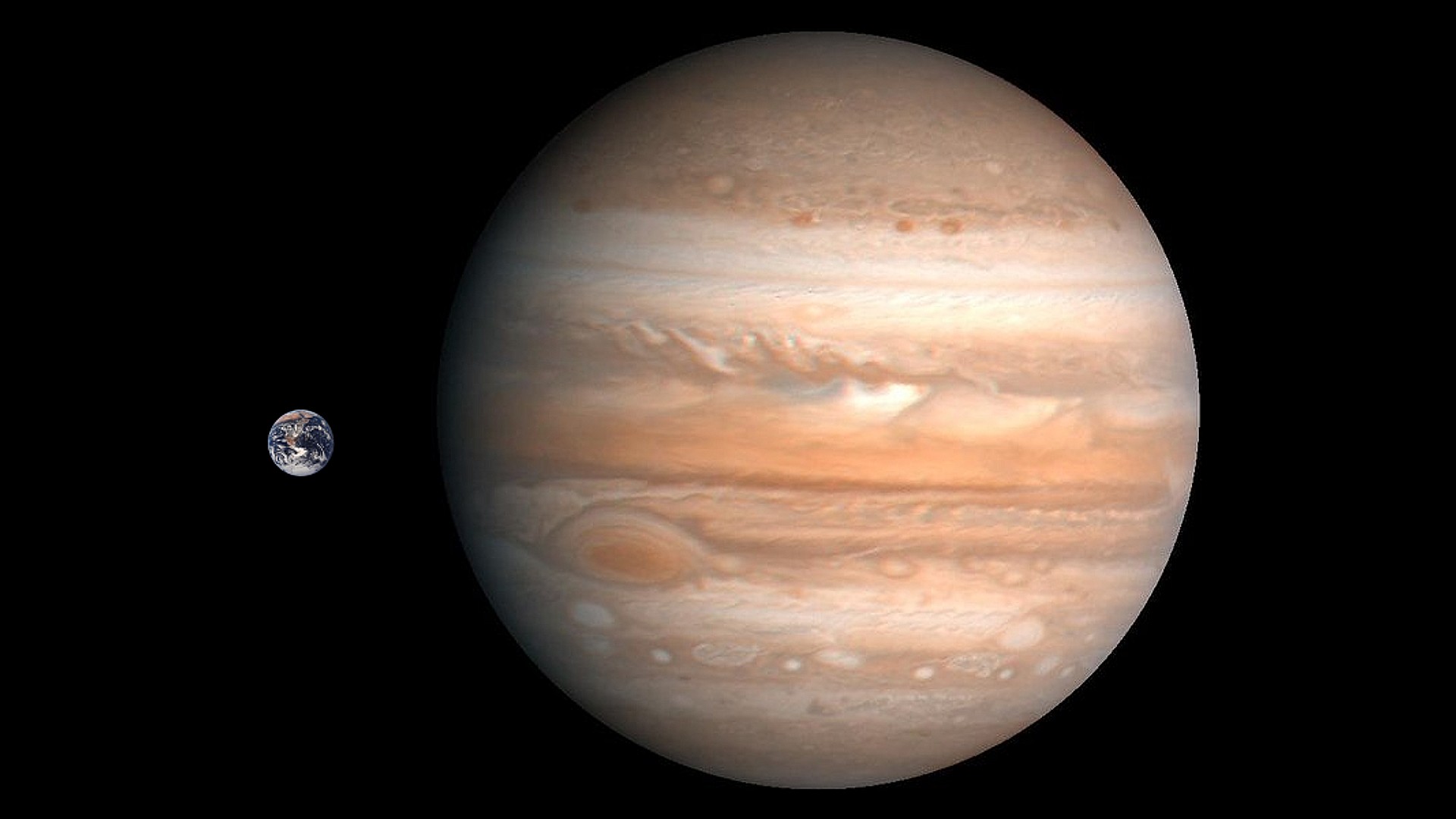

University of California-Riverside (UCR) scientists simulated alternative arrangements of our solar system, finding that when Jupiter's orbit was more flattened — or 'eccentric' — it would cause major changes in our planet's orbit too.

And this change caused by the orbit of Jupiter — the solar system's most massive planet by far — could impact Earth's ability to support life for the better.

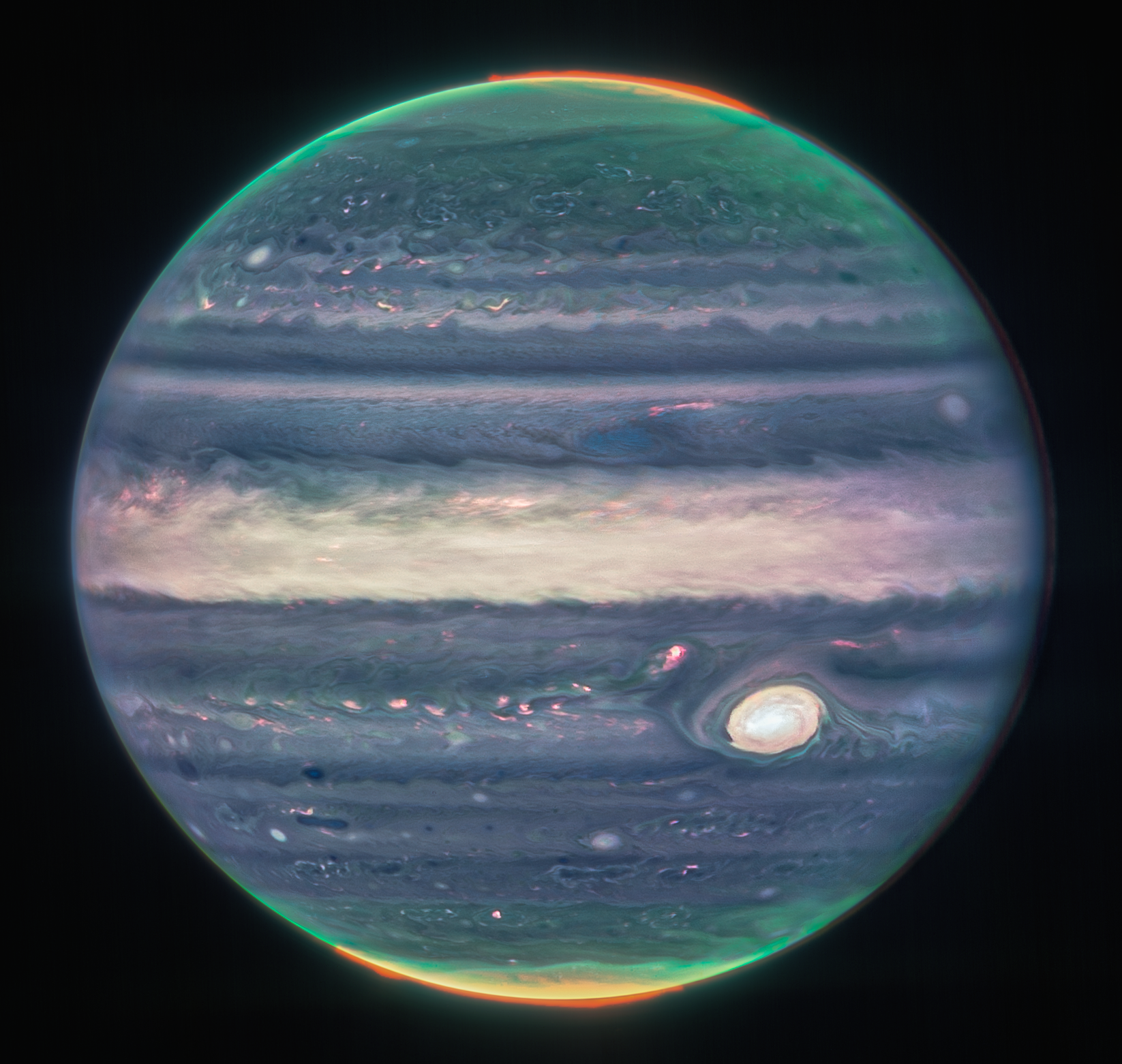

Related: Jupiter's true colors pop in new images from NASA's Juno mission

"If Jupiter's position remained the same, but the shape of its orbit changed, it could actually increase this planet's habitability," study leader and UCR Earth and planetary scientist, Pam Vervoort, said. "Many are convinced that Earth is the epitome of a habitable planet and that any change in Jupiter's orbit, being the massive planet it is, could only be bad for Earth.

"We show that both assumptions are wrong."

Planets with a more circular orbit maintain a steady distance from their star while more eccentric — oval-shaped — orbits bring planets closer and further away from their stars at different points in that orbit. Proximity to a star determines how much radiation it receives and how it is hearted, meaning it affects a planet's climate.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If Jupiter's orbit became more eccentric the team found that Earth's orbit would be pushed into becoming more eccentric too. This means at times Earth would be even closer to the sun than it already gets.

As a result, some of the coldest parts of our planet would warm up reaching temperatures in the habitable range — defined as between 32 and 212 degrees Fahrenheit (0 to 100 degrees Celsius) — for Earth's wide variety of lifeforms.

The team thinks their results could help astronomers determine which planets outside the solar system — exoplanets — could be habitable.

This is because the distance of a planet to its star and its variation determines how much radiation different parts of it receive, creating seasons.

Currently, the habitability search hinges on if a planet is within its star's habitable zone — the area around a star that is the right temperature to allow liquid water to exist — but these results could introduce a new search parameter.

"The first thing people look for in an exoplanet search is the habitable zone, the distance between a star and a planet to see if there's enough energy for liquid water on the planet's surface," UCR astrophysicist, Stephen Kane, said. "Having water on its surface [is] a very simple first metric, and it doesn't account for the shape of a planet's orbit or seasonal variations a planet might experience."

Other factors can influence a planet's habitability, and the team also tested some of these. This includes the tilt of a planet which influences how much radiation it receives from its star.

The UCR scientists found that if Jupiter was much closer to the sun than its current distance of around 461 million miles (742 million kilometers) it could cause extreme tilting on Earth. This would result in our planet receiving less sunlight, meaning that large surface areas of our planet would experience sub-freezing temperatures.

While current telescopes are powerful enough to determine the eccentricity of exoplanet orbits, they aren't as well equipped to measure the tilt of these worlds. This means astronomers are working on methods that could help determine this.

This new research indicates that looking a the orbits and movements of nearby gas giants could help deduce this important factor to habitability.

"It's important to understand the impact that Jupiter has had on Earth's climate through time, how its effect on our orbit has changed us in the past, and how it might change us once again in the future," Kane concluded.

The team's research is published in The Astronomical Journal.

Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom or on Facebook.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.